After decades stored away, this photograph revealed a detail that changes how we understand slavery | HO

The Discovery in the Basement

It began with a box that wasn’t supposed to exist.

Dr. Lisa Morrison, a historian specializing in nineteenth-century photography, was deep beneath the Charleston Heritage Museum—alone amid the dust and silence of a forgotten archive. Her task seemed straightforward: to catalog a neglected collection of pre–Civil War images for a new digital database.

For three weeks, the work was routine—portraits of white families, plantation landscapes, architectural studies. Until, one afternoon, she reached the farthest corner of the storage room and found an unmarked cardboard box wrapped in yellowed tissue.

Inside lay a single daguerreotype, its silver surface still gleaming faintly through layers of age.

The image stopped her cold. A well-dressed white man stood beside a seated Black woman whose plain dress and posture spoke clearly of enslavement. Yet it was not the composition that struck her—it was her eyes.

The woman stared directly into the camera, unflinching, her expression neither submissive nor fearful. It was the gaze of someone aware that she was being recorded—and determined to be seen.

On the back of the plate, in fading ink, Lisa read only:

“Charleston, South Carolina, 1857.”

No names. No notes. Just a silent witness from the edge of history.

The Woman with No Name

Lisa photographed the image, logged it, and then sat staring at it for nearly an hour. She had studied hundreds of antebellum portraits—but this was different. Enslaved people rarely looked straight into the lens. They were depicted as background, property, proof of wealth. But this woman was the subject.

Who was she? And why had her image been hidden away?

That night, Lisa began to dig.

She scoured Charleston’s archives for photographers active in 1857. One name appeared again and again—William Thompson, a daguerreotypist known for his precision portraits. In his studio ledger, Lisa found an entry for March 1857:

“Portrait commission, private residence. Payment received in full. Client: Richard Ashford.”

Ashford, a wealthy cotton merchant, lived in one of Charleston’s grandest homes. His estate records listed dozens of enslaved people—but, as was standard, only by age and labor, not name.

Lisa knew the answer lay elsewhere—in the letters, diaries, and private papers the Ashford family had left behind.

The Name Beneath the Silver

At the South Carolina Historical Society, Lisa unearthed a worn leather journal belonging to Eleanor Ashford, Richard’s sister. Her entries chronicled the rhythm of antebellum life: teas, sermons, visiting relations. But one passage from March 1857 made Lisa’s heart pound.

“I met the woman who manages Richard’s household with such capability. Her name is Hannah. She carries herself with remarkable dignity despite her circumstances. Richard insists on having her portrait made, though I cannot fathom his reasoning.”

Hannah.

For the first time, the woman in the daguerreotype had a name—and a faint voice reaching through time.

A Hidden Lineage

Finding a name was only the beginning. Lisa searched through plantation ledgers, freedmen’s registries, and church archives, but Hannah vanished from the official record after emancipation. It was as if she had never existed.

Then Lisa contacted Dr. James Carter at Howard University, an expert in slave narratives. Within three days, he called back.

“Lisa,” he said, “I think I found her—through her granddaughter.”

He sent an interview from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936. A ninety-three-year-old Charleston woman named Sarah had spoken about her grandmother, Hannah, who had been enslaved before the war.

Sarah recalled,

“Grandma kept a picture of herself in a Bible. She said it proved who she was—proof that she kept her soul even when they tried to break her.”

Lisa froze. The lost photograph Sarah described could only be the daguerreotype in her hands.

The Secret School

Sarah’s testimony painted a portrait of Hannah’s quiet rebellion.

“Grandma said she learned to read and write in secret,” Sarah told the interviewer. “A free colored woman ran a hidden school. Hannah would sneak out on Sundays, saying she was going to church, but really she was learning her letters. She said education was the one thing no master could take from her.”

In the 1850s South, teaching an enslaved person to read was punishable by law. Yet Hannah had risked everything to claim her mind as her own.

Lisa realized this photograph was not just documentation—it was evidence of resistance.

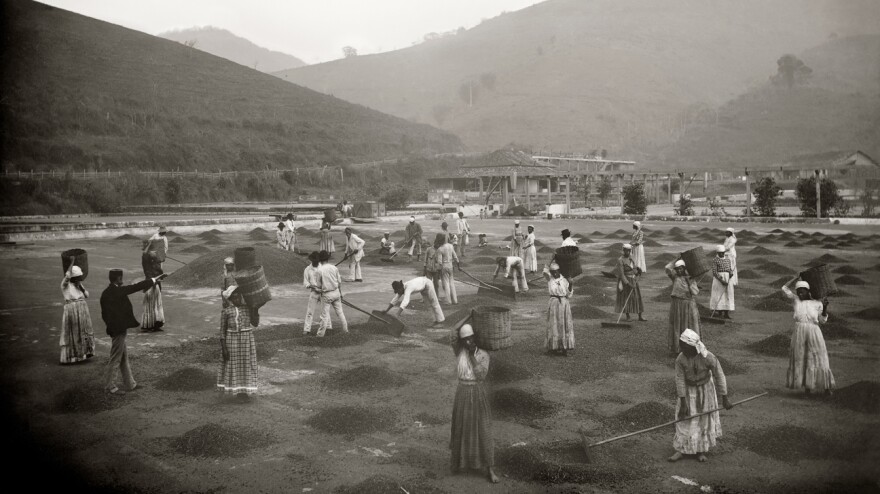

The Sunday Network

Cross-referencing Eleanor Ashford’s journal with city reports, Lisa discovered subtle traces of an underground network of enslaved and free Black women in Charleston. They gathered under the guise of prayer circles, sharing news, literacy lessons, and methods of survival.

One of Eleanor’s entries revealed her unease:

“The women in this district meet often on Sundays. They say it is for worship, but I suspect more than hymns are discussed. Hannah attends faithfully.”

What Eleanor interpreted as suspicion was, in fact, the blueprint of a secret society—one that kept information flowing beneath the surface of a city built on bondage.

The Photograph’s True Purpose

Still, one question haunted Lisa: Why was the photograph taken at all?

Daguerreotypes were expensive. A portrait of an enslaved woman would not have been created without a specific purpose.

While reviewing Richard Ashford’s business letters, Lisa found her answer.

A February 1857 letter from Ashford to his cousin in Boston read:

“You claim that slavery degrades both the slave and the master. I will show you otherwise. I am having the portrait made of the woman who manages my household—proof that slavery here is nothing like your abolitionist fantasies.”

Lisa leaned back in her chair. Ashford had commissioned the photograph as propaganda, a rebuttal to abolitionist criticism.

But Hannah had defied his intent.

Her steady gaze—neither deferential nor broken—turned his instrument of denial into her act of defiance. In that single moment, she had rewritten the meaning of the image.

Even Eleanor noticed it. The day after the sitting, she wrote:

“Richard is pleased with the result, but I confess the woman’s eyes disturb me. There is something in them that refuses its place.”

The Life After Freedom

The Civil War reached Charleston in 1861. By the time Union troops arrived in 1865, Hannah was thirty. Sarah’s testimony filled in what came next:

“Grandma said she walked out that house and never looked back.”

She found work as a seamstress, rented a small room in a boardinghouse run by freedwomen, and began teaching others to read—this time in daylight.

Records from the Freedmen’s Bureau, 1866, confirmed her presence: Hannah Joseph, 31, domestic worker, registered to vote.

She married a freedman named Joseph that same year. They had three children; only one—Sarah’s mother—survived. Hannah lived until 1891, dying at 56, having spent her final decades teaching literacy to anyone who would listen.

“She said education was power,” Sarah recalled. “Keep it in your head, where no one can chain it.”

The Photograph’s Long Journey

For half a century, the photograph vanished. Family tradition held that it burned in a 1903 house fire—but Lisa’s research told a different story.

A collector had salvaged artifacts from the ruins, including a charred Bible and several images. One was listed in an estate sale catalog simply as “Negro woman, Charleston.”

It passed through dealers’ hands until, in 1941, it entered the Charleston Heritage Museum—mislabeled, misfiled, and forgotten.

Until now.

Hannah’s Testament

When Lisa’s report was complete, the museum agreed to feature the daguerreotype in a permanent exhibit titled “Hannah’s Testament: One Woman’s Silent Resistance.”

But Lisa wanted more than an exhibition—she wanted Hannah’s descendants to see her.

Tracing Sarah’s lineage, she found Marcus Johnson, Hannah’s great-great-great-grandson, a history teacher in Atlanta.

When Lisa showed him the photograph, Marcus stood in silence for a long time before whispering, “You found her.”

His daughter, Maya, leaned closer to the glass. “She’s looking right at us,” she said. “Like she knew we’d find her someday.”

Marcus nodded. “She did. That’s why she saved it. She wanted us to know she lived—and that she never bowed.”

The Exhibit That Changed Everything

At the exhibition’s opening, more than two hundred people gathered beneath the museum’s tall brick arches. The daguerreotype was displayed at eye level, surrounded by excerpts from Eleanor’s journal, Sarah’s 1936 testimony, and Lisa’s research on Charleston’s secret literacy networks.

Marcus spoke softly to the crowd:

“My ancestor left no monument, no grave marker. This is her monument. Her face, her eyes, her courage. She looked into that camera and told the truth they tried to bury.”

The audience wept.

The exhibition ran for six months, drawing visitors from across the country. Scholars began reexamining other antebellum images, searching for the same subtle resistance—a glance, a clenched hand, a refusal to look away.

What the Photograph Revealed

The photograph of Hannah did more than identify one woman. It exposed how enslaved people used even imposed acts—portraits meant to objectify them—as moments of reclamation.

Through that gaze, Hannah seized back her humanity.

Dr. Morrison later wrote:

“Her image is not just evidence of oppression—it is proof of endurance. In her stillness lies an unspoken rebellion.”

The Legacy Lives On

Maya Johnson, Hannah’s descendant, later earned her PhD in African American history, writing her dissertation on the hidden schools of enslaved Charleston.

Each year, she visits the museum to stand before her ancestor’s portrait. “When I look at her,” she says, “I see every woman who refused to disappear.”

Hannah’s face now appears in history textbooks, her name inscribed where once there had been silence.

The Last Word

In the end, the photograph that Richard Ashford commissioned to defend slavery became its quietest condemnation.

For more than a century, it waited in darkness. And when it emerged, it spoke—not of submission, but of survival.

When visitors stand before the daguerreotype today, they see more than history. They see a woman who dared to look back.

And through that gaze, we finally see her too.