The night was supposed to be ordinary.

In the quiet suburb of Rowlett, Texas—a place where neighbors knew each other’s names and children rode bicycles down tree-lined streets—June 5, 1996, unfolded like any other summer evening. Families settled into their homes, windows cracked open to let in the warm breeze, sprinklers hissing softly across manicured lawns.

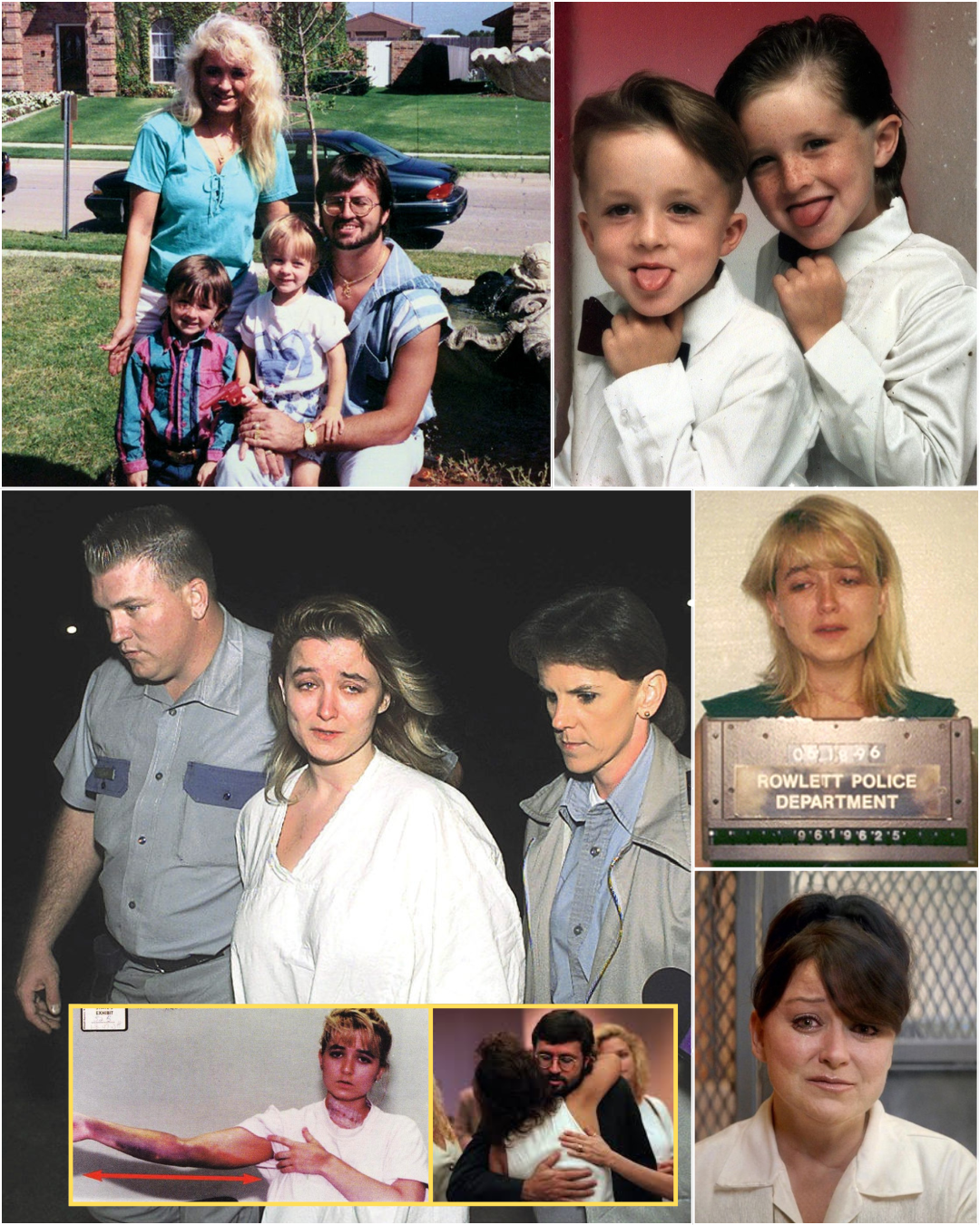

Inside the well-kept brick home at 5801 Eagle Drive, 26-year-old Darlie Routier was living what many would call the American dream. She had a husband, Darin, who worked hard to provide for their family. She had three beautiful boys: six-year-old Devon, with his bright eyes and mischievous grin; five-year-old Damon, gentle and sweet-natured; and seven-month-old Drake, their baby, still cooing in his crib upstairs.

That night, Darlie let Devon and Damon sleep downstairs in the living room—a treat they loved. They curled up on the floor with their pillows and blankets, giggling as they watched television with their mom on the couch nearby. Eventually, the house grew quiet. The boys drifted off to sleep, and Darlie dozed beside them, exhausted from a long day.

Upstairs, Darin slept soundly in their bedroom with baby Drake nestled safely in his crib.

Everything was as it should be.

But at 2:31 a.m. on June 6, 1996, that ordinary night shattered into something unimaginable.

The Call That Changed Everything

The 911 dispatcher in Rowlett, Texas, picked up the line in the early morning darkness, expecting perhaps a medical emergency or a minor accident. What came through instead was a sound that would haunt everyone who heard it: a woman’s voice, ragged and desperate, screaming for help.

It was Darlie Routier.

“Someone broke into my home!” she cried, her words tumbling over one another in panic. “My babies—oh God, my babies! They’re hurt! There’s blood everywhere!”

The dispatcher tried to calm her, to get details, but Darlie’s sobs made it nearly impossible to understand her. She said an intruder—a man—had been in her house. She said he had hurt her boys. She said she tried to chase him away, that he had dropped something as he ran.

The recording of that 911 call would later become one of the most analyzed pieces of evidence in the case—a haunting glimpse into a mother’s worst nightmare, or something else entirely.

Police and paramedics raced to Eagle Drive, their sirens slicing through the stillness of the suburban night. When they burst through the front door of the Routier home, they were met with a scene that would stay with them forever.

A Scene No One Could Forget

Officer David Waddell was the first to arrive.

What he saw when he stepped into the living room stopped him cold. Six-year-old Devon lay on the floor, his small body motionless, eyes open but unseeing. He had already passed away. On the other side of the room, five-year-old Damon was still moving—barely. He crawled slowly along the floor near the wall, making soft gurgling sounds as he struggled to breathe. Blood pooled around both boys, dark and spreading across the carpet.

Paramedics rushed to Damon, working frantically to save him. They lifted him onto a stretcher and hurried him to the ambulance, but the wounds were too severe. He had been hurt deeply—multiple times—and despite their best efforts, Damon passed away during the ride to the hospital.

Devon had been gone before help even arrived.

Both boys had suffered deep, penetrating wounds to their chests and backs—injuries that no child should ever endure.

And there, in the middle of it all, was their mother.

Darlie Routier stood in the living room, visibly shaken, with blood on her nightshirt and wounds on her body. She had cuts on her throat, her right forearm, and her shoulder. One of the wounds on her neck came within two millimeters—just a hair’s breadth—of her carotid artery. If it had gone deeper, she might not have survived either.

She told the officers what she had told the 911 dispatcher: An intruder had broken into their home while they slept. She said she woke up to see a man standing in her living room—a white male, about six feet tall, wearing dark clothing. She said he attacked her and the boys, and then he ran. She said she chased him, that he dropped a knife as he fled through the utility room.

Investigators began combing through the house, looking for signs of this intruder. They found a broken wine glass on the floor. They found a kitchen knife on the counter, its blade stained with blood. In the garage, they discovered a window screen that had been cut, suggesting an entry point for someone breaking in.

And then, perhaps most puzzling of all, they found something down the alley behind the house: a sock. It was about 75 yards away from the home, and it was covered in blood.

Everything seemed to line up with Darlie’s story.

But as the sun rose over Rowlett that morning, casting light on the tragedy that had unfolded in the night, investigators began to notice things that didn’t quite fit.

The Questions That Wouldn’t Go Away

Darlie Routier was rushed to the hospital for treatment. Her wounds were serious enough to require medical attention, but doctors noted something that would later become a point of contention: her injuries, while painful, were described as “superficial” compared to the devastating wounds her sons had suffered.

The surgeon who treated her told police that her cuts appeared to be about half an inch deep—not nearly as severe as the deep puncture wounds that had taken the lives of Devon and Damon.

Still, a wound is a wound, and Darlie had clearly been hurt. She was released from the hospital two days later and returned home to a house that would never feel the same.

Upstairs, her baby Drake and her husband Darin had both been unharmed that night. They had slept through the entire attack, waking only when Darlie called for help.

The Rowlett Police Department launched what they would later describe as “the most intensive and exhaustive investigation ever conducted” in their department’s history. Detectives interviewed Darlie multiple times, retracing her story, asking her to walk them through the events of that night over and over again.

And each time, small inconsistencies began to emerge.

Why, investigators wondered, had Darlie not woken up immediately when the intruder attacked her and her children ? The wounds inflicted on her sons were brutal and would have required significant force. How could she have slept through that, only waking up after the attack was already underway ?

Why were her injuries so much less severe than those of her boys ? If an intruder had truly attacked them all, why would he hurt the children so deeply but only wound Darlie superficially ?

And then there was the matter of the crime scene itself.

Crime scene consultant James Cron arrived at the house to examine the evidence. As he walked through the living room, the kitchen, and the garage, something about the scene troubled him. He had worked countless crime scenes over his career, and he knew what a real break-in looked like.

This, he would later testify, did not look like a real break-in.

The broken wine glass on the floor seemed oddly placed. The cut window screen in the garage showed no signs of anyone actually climbing through it—no dirt, no disturbance of the items below it. And most troubling of all, there were no signs of a struggle that would suggest someone had fought off an intruder.

Cron’s professional opinion was chilling: the scene had been staged.

The Sock in the Alley

One piece of evidence, however, seemed to support Darlie’s story.

The bloody sock found 75 yards down the alley behind the house contained blood from both Devon and Damon. If Darlie had truly staged the crime scene and hurt her own children, how could she have run all the way down the alley to plant the sock, come back, cut herself, and then called 911 ?

The defense would later argue that this sock was proof of Darlie’s innocence—that it proved an intruder had fled the scene, taking the sock with him.

But prosecutors had a different theory.

They believed that Darlie had planted the sock before anything else happened. They theorized that she ran down the alley in the middle of the night, dropped the sock to create the illusion of an intruder’s escape route, then returned home to carry out the unthinkable.

Medical examiners testified that Damon could have survived approximately eight minutes after receiving his injuries. Eight minutes. That would have been enough time, prosecutors argued, for Darlie to plant the sock, stage the scene, and inflict her own wounds before calling for help.

It was a theory that painted a horrifying picture—one that the people of Rowlett, and soon the entire nation, struggled to comprehend.

A Mother Under Suspicion

Less than two weeks after the deaths of Devon and Damon, Darlie Routier was arrested.

On June 18, 1996, investigators from the Rowlett Police Department took her into custody and charged her with two counts of capital murder in the deaths of her sons. She was held under suicide watch in Dallas County’s central jail.

“I did not murder my children,” Darlie said, her voice breaking. “I had nothing to do with this.”

But the evidence against her was mounting.

Forensic experts analyzed the blood spatter patterns in the house and found something disturbing. Tom Bevel, a blood spatter analyst, testified that cast-off blood was found on the back of Darlie’s nightshirt—blood that indicated she had raised a knife over her head and brought it down multiple times. The pattern, he said, was consistent with someone stabbing downward repeatedly, then withdrawing the knife and stabbing again.

It was the kind of pattern that would be left behind by someone attacking another person.

Not by someone defending themselves.

Prosecutors began building their case, and as they did, they developed a theory about why Darlie Routier might have done the unthinkable.

The Motive

At her trial, which began on January 6, 1997, in Kerrville, Texas, prosecutors painted a picture of a woman under immense stress.

They described Darlie as “a self-centered woman, a materialistic woman, and a woman cold enough to murder her own two children”. They argued that the Routier family was facing financial difficulties, that their lavish lifestyle was becoming unsustainable, and that Darlie saw her sons as burdens she could no longer afford.

Both Devon and Damon had small life insurance policies on them—$5,000 to $10,000 each. Prosecutors suggested that Darlie had killed her boys to collect on those policies.

The defense, however, pointed out the absurdity of that motive. Ten thousand dollars was barely enough to cover funeral expenses, they argued. If Darlie truly wanted money, why wouldn’t she have harmed her husband instead ? Darin had an $800,000 life insurance policy.

And why, if she was willing to take the lives of her children, had she left baby Drake unharmed upstairs ?

The defense maintained that there was no clear motive, no confession, and no eyewitnesses. They argued that Darlie was a loving mother who had been the victim of a brutal attack—not the perpetrator.

But then the prosecution introduced a piece of evidence that would change everything.

The Video That Shocked the Nation

Eight days after the deaths of Devon and Damon, the Routier family held a graveside gathering to celebrate what would have been Devon’s seventh birthday.

Family and friends gathered at the cemetery, balloons tied to the headstones, the Texas sun beating down on them as they remembered the two boys who had been taken too soon.

A local television station was there to film the event.

What they captured would become one of the most controversial pieces of evidence in the entire case.

The video showed Darlie Routier standing at her sons’ graves, smiling. She was holding a can of Silly String—the kind children use at birthday parties—and she was spraying it over the headstones, laughing and singing “Happy Birthday”.

“Even though our hearts are breaking,” Darlie told the television station, “I know that Devon and Damon would want us to be happy.”

When that video aired on the news, the reaction was swift and visceral.

How could a mother, just days after losing her children, be smiling and laughing at their graves ? How could she be playing with Silly String, as if this were a celebration instead of a tragedy ?

To many people watching, the video was proof that something was deeply wrong. It didn’t look like the behavior of a grieving mother. It looked like the behavior of someone who wasn’t grieving at all.

At trial, prosecutor Toby Shook played a 15-second clip of the Silly String video for the jury. He told them that it gave them “a lot of insight into this woman”.

But what the jury didn’t see—what wasn’t shown in that brief clip—was what had happened earlier that day.

Before the birthday gathering, the Routier family had held a solemn, private memorial service for Devon and Damon. Police had secretly recorded that service, and it showed a very different Darlie: a woman sobbing, her face crumpled in grief, barely able to stand as she said goodbye to her sons.

The defense argued that the Silly String video had been taken out of context, that it represented a brief moment of levity in an otherwise unbearable day—a moment meant to honor the boys’ memory in the way they would have wanted.

But the damage was done.

The image of Darlie smiling and spraying Silly String at her sons’ graves was seared into the public consciousness, and it became a symbol of everything the prosecution was trying to prove.

The Verdict

The trial lasted nearly five weeks.

Prosecutors called 38 witnesses, methodically presenting their case that Darlie had staged the crime scene, planted the sock, inflicted her own wounds, and taken the lives of her two young sons. They argued that the forensic evidence—the blood spatter on her nightshirt, the lack of a true struggle, the superficial nature of her injuries—all pointed to one inescapable conclusion.

The defense fought back, presenting their own experts who challenged the prosecution’s forensic analysis. San Antonio chief medical examiner Vincent DiMaio testified that the wound to Darlie’s neck came within two millimeters of her carotid artery and that it was not consistent with self-inflicted wounds he had seen in the past. He believed her injuries were real, not staged.

But the jury had to weigh all the evidence: the blood patterns, the crime scene, the lack of forced entry, the sock in the alley, and that haunting Silly String video.

On January 31, 1997, the case went to the jury.

The following day, they reached a verdict.

Darlie Routier was found guilty of the capital murder of her five-year-old son, Damon. Because of his age, the crime was punishable by death under Texas law.

On February 4, 1997, she was sentenced to death by lethal injection.

She has never been tried for the murder of six-year-old Devon, though she remains charged in his death as well.

Darlie Routier was taken to the Patrick O’Daniel Unit (formerly Mountain View Unit) in Gatesville, Texas, where women sentenced to death under Texas law are housed. She has been on death row now for more than 28 years.

And she has maintained her innocence every single day.

The Doubts That Remain

From the moment the guilty verdict was announced, questions began to swirl around Darlie Routier’s case—questions that have only grown louder in the nearly three decades since.

Was justice truly served that day in the Kerrville courtroom, or had the jury gotten it wrong ?

For those who believe in Darlie’s guilt, the evidence is clear. The blood spatter on her nightshirt, the superficial nature of her wounds, the staged crime scene—all of it points to a woman who committed an unspeakable act and then tried to cover it up.

But for those who believe in her innocence, the case against Darlie is riddled with holes, contaminated evidence, and questionable forensic testimony.

And as the years have passed, more and more people have begun to wonder if the state of Texas got it wrong.

The Defense That Never Was

One of the most significant criticisms of Darlie’s trial centers on the defense her attorney mounted—or rather, didn’t mount.

Doug Mulder, Darlie’s trial attorney, presented medical and psychiatric experts who testified that her wounds did not appear to be self-inflicted and that they believed she was telling the truth about the intruder. Dr. Vincent DiMaio, the San Antonio chief medical examiner, told the jury that the cut to Darlie’s throat came within two millimeters of her carotid artery—a wound that could easily have been fatal.

But Mulder made a critical error: he did not present any forensic experts to challenge the prosecution’s theory that the crime scene had been staged.

The prosecution’s case rested heavily on forensic evidence—blood spatter analysis, crime scene reconstruction, fiber analysis. Yet Mulder called no one to rebut those claims.

In his closing argument, Assistant District Attorney Greg Davis seized on this silence. “It speaks volumes to you sometimes what you don’t see and hear,” he told the jury.

It was a devastating blow.

Years later, Darlie’s appellate attorneys would argue that Mulder’s failure to present forensic testimony constituted ineffective assistance of counsel—a legal standard that, if proven, could warrant a new trial.

But the Texas courts denied that claim, as they have denied every other appeal Darlie has filed.

Still, the question lingers: What if the jury had heard a different side of the forensic story ?

The Blood Spatter Controversy

At trial, the prosecution’s blood spatter expert, Tom Bevel, testified that cast-off blood on the back of Darlie’s nightshirt proved she had raised a knife over her head and brought it down repeatedly, stabbing her sons.

It was powerful testimony, and it helped seal Darlie’s fate.

But in the years since, that testimony has come under intense scrutiny.

Darlie’s appellate team brought in their own blood spatter experts—Bart Epstein and Terry Laber, both highly respected in the field of forensic science. They conducted their own experiments and came to a very different conclusion.

They believed that the blood on Darlie’s nightshirt could have been the result of transfer—blood that got onto the fabric when she tried to help her dying children, or when police officers and paramedics moved through the scene, contaminating evidence.

Defense attorney Stephen Cooper, who has been working on Darlie’s case for years, said the experiments staged by Epstein and Laber were eye-opening. “Watching the re-enactments left a far more powerful impression than when I talked with the pair about their findings about 10 years ago,” he said.

The problem, of course, is that the jury never saw those re-enactments.

They never heard from Epstein or Laber.

They only heard from Tom Bevel, and they believed him.

The Hair That Didn’t Belong

Another piece of evidence that has raised questions is a hair that was found on the windowsill in the garage—the same window where the screen had been cut.

At a bond hearing prior to Darlie’s trial, Charles Linch, a forensic analyst from the Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences, testified that the hair belonged to Darlie. It was a critical piece of evidence because it suggested she had been the one to cut the screen, staging the crime scene to look like a break-in.

But there was a problem with Linch’s testimony.

He was not certified in fiber analysis and had not completed a proficiency test at the time. He had previously only worked as a microscopic hair analyst.

Months later, DNA testing proved that the hair did not belong to Darlie at all. It belonged to a female police officer who had contaminated the crime scene.

Linch’s erroneous testimony, critics argue, was a crucial factor in keeping Darlie incarcerated.

Yet despite this revelation, Darlie remains on death row.

The Sock That Still Doesn’t Make Sense

The bloody sock found 75 yards down the alley behind the Routier home remains one of the most perplexing pieces of evidence in the case.

The sock contained blood from both Devon and Damon, but none from Darlie. If she had truly staged the crime scene and planted the sock herself, wouldn’t her blood have been on it too ?

At trial, the prosecution argued that Darlie had run down the alley and planted the sock before anything else happened, which is why it didn’t have her blood on it. But defense attorneys have pointed out the absurdity of that timeline.

If Darlie ran down the alley, came back, attacked her children, cut herself, staged the scene, and then called 911, all within the span of a few minutes, how did no one see or hear anything ?

The Routier home was in a suburban neighborhood with houses close together. Surely someone would have noticed a woman running down an alley in the middle of the night, covered in blood.

And yet, no witnesses ever came forward.

Attorney Richard Burr, who has worked on Darlie’s post-conviction petition, has argued that the sock is proof of an intruder. “That athletic sock had both boys’ blood on it but none of Routier’s,” he wrote in legal filings.

The prosecution’s theory about the sock, Burr believes, simply doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

The Bruises No One Saw

During Darlie’s hospital stay, photographs were taken of her injuries.

At trial, those photos showed the cuts on her throat and arms—the wounds the prosecution argued were self-inflicted.

But what the jury didn’t see clearly at trial were the bruises on Darlie’s arms.

In the days following the attack, those bruises became more pronounced, darkening and spreading across her skin. Medical staff at the hospital documented them, noting that they were consistent with defensive wounds—the kind of injuries someone might sustain while fighting off an attacker.

The prosecution, however, suggested that Darlie had inflicted the bruises on herself after the fact, in an attempt to support her story.

But many experts have pointed out that bruising takes time to develop. The bruises photographed during Darlie’s hospital stay were present at the time of the attack, not created afterward.

If Darlie had truly staged everything, would she have had the foresight—and the physical ability—to bruise herself in a way that would look authentic days later ?

It’s a question that has never been satisfactorily answered.

The Fight for DNA Testing

Perhaps the most significant development in Darlie Routier’s case in recent years has been the fight for DNA testing.

In 2008, a Texas court granted Darlie the right to have DNA testing performed on evidence from her case. The hope was that modern DNA technology, which has advanced considerably since the 1990s, might reveal something that was missed during the original investigation.

But actually getting that testing done has proven to be a bureaucratic nightmare.

Defense attorneys have fought for years to obtain court approval for DNA testing of the blood spatter evidence found throughout the lower floor of the Routier home. Yet progress has been excruciatingly slow.

In 2017, a status report revealed that the materials that were supposed to have been transported to the Department of Public Safety for DNA testing had never been transported at all. They had simply been sitting somewhere, untested, while Darlie remained on death row.

“Though a court has ordered DNA testing that could verify Routier’s burglary story, bureaucratic delays have kept her waiting on death row,” a 2018 report noted.

Then, in 2021, there was a breakthrough.

The Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted individuals through DNA testing, entered the case. Their involvement brought new momentum to the efforts to have evidence tested.

In September 2021, Judge Audra Riley of Dallas County signed an order instructing multiple agencies—including the Dallas County District Clerk, the Rowlett Police Department, and the Texas Department of Public Safety—to collect their evidence from the Routier case and send it to the Forensic Analytical Crime Laboratory in California.

The testing would be performed on the bloody sock, hairs recovered from the sock, Darlie’s shirt, blankets and pillowcases found at the scene, a bloody knife, and other critical pieces of evidence.

The Innocence Project agreed to pay for the shipment of evidence between laboratories.

One of Darlie’s attorneys, Richard R. Smith, called the judge’s order “welcome news”.

“We wanted it,” he said simply.

As of 2024, however, the results of these DNA tests are still pending.

Nearly 30 years after the deaths of Devon and Damon Routier, the answers that modern science might provide remain just out of reach.

A Mother Who Never Stopped Fighting

Inside the Patrick O’Daniel Unit in Gatesville, Texas, Darlie Routier waits.

She has spent more than half of her life on death row, longer than many people thought possible. Texas is known for carrying out executions swiftly, but Darlie’s case has been tied up in appeals for decades.

Every day, she wakes up in the same place, surrounded by concrete and razor wire, living with the knowledge that the state believes she took the lives of her own children.

And every day, she maintains her innocence.

“I did not murder my children,” she has said over and over again. “I had nothing to do with this.”

Her ex-husband, Darin Routier, believes her. Despite the strain the case put on their marriage—they eventually divorced—Darin has never wavered in his conviction that Darlie is innocent.

“I know my wife,” he has said. “She could never do something like this.”

Darlie’s mother, Darlie Kee, has spent the past 28 years fighting for her daughter. The struggle, she admits, has been wearing.

“It’s been 22 years,” Kee said in a 2018 interview, “and I’m tired”.

But she refuses to give up.

In 2018, Kee planned a “Convoy for Justice” to Dallas, hoping to gain the ear of Texas Governor Greg Abbott. She has watched as supporters of Darlie have doubled in number, particularly after the case was featured on the ABC series The Last Defense, a documentary that examined whether Darlie received a fair trial.

Kee believes her daughter was railroaded. She believes the prosecution used character assassination to sway the jury, depicting Darlie as a cold, calculating mother who killed her children for insurance money—a theory that, to this day, many people find hard to believe.

“She didn’t get a fair trial,” Kee has said.

And she’s not alone in that belief.

The Case That Divided a Nation

Few cases in American criminal justice have sparked as much debate as the case of Darlie Routier.

On one side are those who believe the evidence is overwhelming—that Darlie staged the crime scene, hurt her children, and then lied to cover it up. They point to the blood spatter, the Silly String video, the lack of forced entry, and the inconsistencies in her story.

To them, Darlie is exactly where she belongs: on death row, paying the price for an unthinkable crime.

On the other side are those who believe Darlie is innocent—a victim not of an intruder that night, but of a flawed investigation, questionable forensics, and a justice system that rushed to judgment.

They point to the contaminated evidence, the hair that didn’t belong to Darlie, the bruises on her arms, the sock in the alley, and the fact that her defense attorney failed to mount an adequate defense.

To them, Darlie is an innocent woman who has spent nearly 30 years on death row for a crime she didn’t commit.

The truth, as it so often does, may lie somewhere in the evidence that has yet to be fully examined.

What the DNA Might Reveal

When the DNA results finally come back—and they will, eventually—they could change everything.

If the testing reveals the presence of unknown male DNA on the sock, the knife, or anywhere else in the house, it would lend credence to Darlie’s story about an intruder.

If it shows that the blood on Darlie’s nightshirt came from transfer rather than cast-off spatter, it would undermine one of the prosecution’s key pieces of evidence.

If it confirms the presence of contamination—DNA from police officers, paramedics, or other people who were at the scene—it would raise serious questions about the integrity of the evidence used to convict her.

But if the DNA testing supports the prosecution’s theory—if it shows no sign of an intruder, no evidence of contamination, and confirms the blood spatter analysis—then it would provide the final, definitive proof that Darlie Routier is guilty.

Either way, the DNA holds the answers.

And until those answers come, Darlie will continue to wait.

The Boys Who Never Got to Grow Up

Lost in the legal battles, the forensic debates, and the media circus that has surrounded this case are two little boys who never got the chance to grow up.

Devon Routier would have turned 35 years old in 2025. Damon would have been 34.

They should have had the chance to go to school, to play sports, to fall in love, to build lives of their own.

Instead, they are forever frozen in time—Devon at six years old, Damon at five—remembered only through photographs and the memories of those who loved them.

Their grandmother, Darlie Kee, still honors them. In 2018, she planned a convoy to Dallas in honor of what would have been Devon’s 30th birthday.

Their father, Darin, still grieves for them.

And their mother—whether guilty or innocent—has spent nearly three decades unable to hold them, to see their faces, to tell them she’s sorry for whatever happened that night.

A Question That May Never Be Answered

On June 6, 1996, something terrible happened in a suburban home in Rowlett, Texas.

Two little boys lost their lives.

A mother’s world was shattered.

And a community—a state, a nation—was left asking a question that may never be fully answered: What really happened that night ?

Did an intruder break into the Routier home, attack Darlie and her sons, and then vanish into the darkness, leaving no trace behind ?

Or did Darlie Routier, in a moment of desperation or madness that no one can fully explain, take the lives of her own children and then stage an elaborate cover-up ?

For nearly 30 years, the justice system has said it knows the answer. The jury found her guilty, the judge sentenced her to death, and the appeals courts have upheld that verdict time and time again.

But doubt remains.

Doubt in the forensic evidence. Doubt in the investigation. Doubt in whether Darlie Routier truly received a fair trial.

And so she waits, in a cell in Gatesville, Texas, for the DNA results that might finally tell the world what happened on that terrible night in June 1996.

She waits for justice—whether that justice means her exoneration and release, or her execution.

She waits, as she has waited for nearly three decades, for someone to believe her when she says, “I did not murder my children”.

And somewhere, in a cemetery in Texas, two little boys rest beneath headstones that bear their names and the dates they were born and died—dates that are far, far too close together.

Devon, who loved to play and laugh.

Damon, who was gentle and kind.

They deserved so much more than they got.

And whether their mother is guilty or innocent, that is a truth no one can deny.

The case of Darlie Routier is not just a story about murder, forensics, or the death penalty.

It’s a story about two boys who never got to grow up, a mother who may or may not be responsible for their deaths, and a justice system that is supposed to get it right every time—but doesn’t always.

It’s a story that began on a warm summer night in 1996, and one that, nearly 30 years later, still has no ending.

Not yet.

But someday, perhaps, the DNA will tell us what really happened.

And when it does, we will finally know whether Darlie Routier is a grieving mother who lost everything, or a woman who took everything from her own children.

Until then, the question remains.

What really happened that night ?