HOA Banned My Well Water – So I Dried Out Their Golf Cours

Part One

They thought they could break me.

That’s the funny thing about people who’ve never had to fight for land—they think a few letters, a few fines, a meeting in a conference room can shatter a life that was built before they were born.

My name is Jake Miller. I’ve lived on the same patch of earth in northern Texas since before I could pronounce my own last name. My granddad bought this place after World War II with a mix of Army pay and pure stubbornness. Three generations of Millers have bled, sweated, and buried dogs and dreams out here. This farm isn’t property to me. It’s family.

For the longest time, our nearest neighbors were mesquite trees and grasshoppers. Then about fifteen years ago, the developers came.

First it was survey stakes in the distance, then cement trucks, then the slow raising of beige palaces with stone veneers and two-story entryways. They called the place “Sagebrook Reserve Golf & Estates,” as if giving it a poetic name could hide the fact it used to be pasture.

Suddenly there were shiny SUVs on the county road, manicured women in athleisure walking designer dogs, and a green oasis of eighteen holes cut and watered like God himself was their groundskeeper. Along with the houses came a three-letter curse: HOA.

Homeowners Association. Three words that have ruined more Thanksgiving dinners than political arguments.

At first, I didn’t mind. They stayed inside their gates and I stayed outside them. Their world was keyed entry pads and security cameras. Mine was wire fences and a well that tasted like iron and childhood.

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that some people cannot stand the sight of a life they don’t control.

The first letter arrived two years after the last house went up.

Dear Mr. Miller,

We hope this letter finds you well. Several residents have expressed concern about the appearance of your barn and equipment visible from the 5th and 6th fairways…

They suggested fresh paint “to maintain property values” and offered the HOA’s “preferred vendors” at a “discount.”

I laughed, tossed it in the woodstove, and went back to mending fence.

The second letter wasn’t so polite. It cited “noise complaints” from tractors “operating at unreasonable hours” and “offensive odors” from livestock. There was a line in bold at the bottom:

Failure to comply may result in further action.

I called the number on the letter, asked to speak to whoever thought a rooster crowing at dawn was a violation.

“This is Robin Matthews, president of the Sagebrook HOA,” came a crisp voice. “We’ve had numerous complaints. Our residents paid good money for peace and quiet.”

“Ma’am,” I said, “my granddad was plowing this land when your good-money residents were in junior high. This is a working farm. Tractors run, cows smell, and the barn looks like a barn. You don’t like the view, plant some trees on your side of the fence.”

She made a sound like she’d bitten into a lemon.

“You’re not within our association, Mr. Miller, but your property impacts our community,” she said. “We’re prepared to reach out to the county if necessary.”

“You do that,” I said, and hung up.

That should’ve been the end of it. Live and let live. But beneath that manicured sod was a vein of entitlement that ran deep.

The complaints escalated. Someone from the county zoning board came by, saying an anonymous report had flagged my barn as “structurally unsound.” I showed him the beams, the braces, the fresh lumber I’d put in just three summers ago.

He shrugged. “Looks fine to me, but the board might want an engineer’s report.”

An engineer’s report. For a barn that had outlived three county commissioners.

I started to feel like there was a target on my back.

Then the drought hit.

Texas flirts with drought every few years, but this one landed serious. Creeks shrank to muddy strings, stock ponds cracked along the edges like old paint. The county issued restrictions on outdoor watering. No lawn sprinklers, no car washing, no non-essential use.

For Sagebrook, “non-essential” was a word they were determined to redefine.

See, their golf course wasn’t hooked up to city water. When they built it, they struck a deal with the county’s water improvement district to tap into the aquifer that sat beneath all our land. They drilled a deep well on a corner parcel the developer still technically owned. It was just big enough to be non-contiguous with my fence line, just far enough to pretend their water didn’t come from the same belly of earth that filled my well.

My own well was old but solid. Granddad had it dug the year after he bought the place. We’d replaced the pump once, upgraded the casing, but the water still came up cold and clear.

Then one afternoon, a county truck pulled into my drive. Two men climbed out—one in a collared shirt with a clipboard, the other in a reflective vest with a tool bag.

“You Jake Miller?” Clipboard asked.

“Last I checked,” I said. “What can I do for you?”

“We’re here to install a flow restrictor on your well,” Vest said. “New emergency drought ordinance. Non-municipal wells must comply.”

I stared at him. “Come again?”

Clipboard cleared his throat and read from a sheet.

“Section 14.3: In times of declared water emergency, all private wells in the unincorporated district will be subject to usage limits as determined by the Water Conservation Board.”

“Funny,” I said, “because last time I was at a board meeting, they assured us grandfathered agricultural wells wouldn’t be touched. We rely on this for livestock and crops.”

“The board reviewed and updated the language,” Clipboard said. “We mailed notices.”

I thought of the stack of HOA letters I’d burned without reading and felt a cold stone drop into my gut. They must’ve slipped that one in with the rest.

My jaw tightened.

“You’ll put your hands on that wellhead over my dead body,” I said.

Vest shifted, eyes flicking up the drive. “We’ve got legal authority, sir. Refusal to comply can result in fines and possibly a lien.”

“A lien on land that’s been in my family seventy years because I watered my cows?” I asked, my voice rising.

“This isn’t personal,” Clipboard said. “The HOA petitioned the board. They claim your usage is excessive, that it jeopardizes the water table the entire community depends on, including the municipal well that feeds their irrigation system.”

I laughed once, sharp and humorless.

“Their irrigation system?” I said. “You mean their golf course sprinklers?”

“You shouldn’t think of it that way,” Clipboard said lamely. “We’re all in this together.”

I looked past them, toward the line of green that glowed unnaturally even in late afternoon, fairways lush while my pasture went gold.

“Are they getting restrictors?” I asked.

“That’s… a different contract,” Vest muttered.

There it was. They were coming for my well while their sacred putting greens drank freely.

“Get off my property,” I said, voice flat.

“Mr. Miller—” Clipboard started.

“I said get off,” I repeated. “You and that ordinance can take a hike. You want to touch my well, you bring a sheriff and a judge’s order. Not a piece of paper you cooked up in a meeting that smelled like Chardonnay.”

Vest shifted his tool bag from one hand to the other. He didn’t look eager to test me.

Clipboard narrowed his eyes. “We’ll note your refusal,” he said. “Expect correspondence from the county and possibly legal action.”

“Can’t wait,” I said.

They left a bright orange violation notice taped to my gate.

Three days later, a sheriff’s deputy did show up—but not for the well.

I came back from checking fence on the north forty to find dust clouds and diesel fumes in the air. A bulldozer sat beside my barn, its blade lowered. The west wall of the barn sagged inward, boards splintered where the bucket had punched through.

A crew in hard hats and neon vests moved around like ants on a nest.

I slammed on my brakes so hard my truck fishtailed in the gravel.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” I shouted, throttle forgotten as I flew out of the cab.

A man with a clipboard and a smug tucked-in polo turned toward me.

“Mr. Miller? We’ve been contracted by Sagebrook Development and authorized by the county to remove a non-compliant structure that violates setback and safety regulations.”

He said it like he was reciting a recipe.

“This barn was here before Sagebrook was a twinkle in a realtor’s eye,” I said. “You’re on private land.”

“We have an order,” he said, holding up a crumpled paper with the county seal. “Structure has been deemed unsafe by Code Enforcement.”

“That’s not your call to make,” I snarled. “Back your toys off my building before I introduce that bulldozer to the bottom of the creek.”

“Sir, step back,” another worker said. “You’re interfering with a legal operation.”

Behind me, a sheriff’s cruiser rolled up, gravel crunching. Deputy Lang stepped out, hand resting on his belt.

“Jake,” he said, walking toward me. “Take it easy.”

“Tell them to get off my land,” I said, pointing at the torn barn wall. “You know damn well this is out of bounds.”

He glanced at the paper in Polo’s hand, eyes skimming the text.

“Looks like the county signed off on this,” he said quietly. “Jake, if you interfere, they’ll call it obstruction. I can’t arrest half the construction company. I can arrest you.”

My pulse pounded in my ears.

“They’re tearing down my barn,” I said. “On my land. For an HOA I’m not part of.”

“Civil matter,” Lang said, almost apologetic. “You want to fight it, take it up in court.”

It was the same line he’d used when kids trespassed or when a developer cut through someone’s field to lay fiber optics.

This was bigger. And they all knew it.

I stood there, fists clenched, and watched as the dozer took another bite out of my barn. Boards snapped. Nails squealed. Dust rose.

They left the structure half-gutted, one wall gone, rafters exposed to the sky like ribs. A notice flapped in the wind:

NON-COMPLIANT STRUCTURE MUST BE REMOVED WITHIN 30 DAYS.

That night, I sat at my kitchen table with a beer and a stack of their notices fanned out like playing cards. Fines for “failure to comply.” Threats of liens. “Further enforcement action.”

I stared at the orange violation papers until the text blurred.

Enough.

They thought they had all the leverage—county connections, lawyers, money, a sheriff who didn’t want trouble. They’d forgotten one thing.

I knew this land better than any of them.

I knew its history.

And buried in that history was their softest spot.

Their weakness.

Water.

Part Two

My grandfather, Thomas Miller, fought in the Pacific and came home with a permanent hitch in his step and a deep distrust of bureaucrats. He liked things he could see, touch, measure. Wells. Ditches. Fenceposts. Deeds.

When he bought our place in 1947, it came with more than cows and pasture. Running along the back fence line was a narrow, spring-fed creek that cut across three properties before it joined a larger branch and eventually emptied into the river.

It wasn’t much to look at most years—knee-deep in places, ankle-deep in others—but it ran almost year-round. In summer, when other folks’ ponds dried up, our creek still trickled.

The county, perpetually broke, had once approached Granddad about using that creek as part of a new agricultural irrigation network. He’d agreed—on paper, in a meeting with a county lawyer who’d thought he was getting one over on a simple farmer.

Granddad had only come up to eighth grade, but he read every line of that contract with care. And when he saw an opportunity, he took it.

The contract granted the county the right to lay a small concrete diversion box and pipeline at the point where the creek entered our land. In exchange, the county agreed to maintain that structure and run water to a series of downstream farms and, eventually, to any “future agricultural or recreational uses authorized by the board.”

But Granddad insisted on a clause, one the county attorney thought harmless at the time.

Primary water rights and control of flow point shall remain with the landowner, his heirs and assigns.

Heirs and assigns. That meant me.

For decades, nobody thought much about it. The water flowed, cows drank, farmers irrigated. Then Sagebrook came along, and the county, seeing dollar signs, repurposed that old agricultural line into a feed for the golf course’s irrigation system.

They extended the pipeline, upgraded pumps, and bragged to investors about their “independent water source.”

They never renegotiated the rights with my family.

I found all this in a dusty file box in Granddad’s old office after the barn incident. The cardboard had gone soft with age; the papers inside smelled like mildew and tobacco.

There it was: the original Water Use Agreement from 1962, with my grandfather’s shaky signature and the county attorney’s flourish. Attached were amendments, none of which changed that one key sentence.

Primary water rights and control of flow point shall remain with the landowner, his heirs and assigns.

On top of the stack was a sticky note in Granddad’s handwriting, taped there years ago, maybe when he started to worry his mind might go before his body.

If they ever get too big for their britches, follow the water. – T.

I sat back in the old spinning chair, the weight of the paper in my hand and something electric starting behind my ribs.

The developers must have either missed this clause or assumed no one would care. They’d built a multimillion-dollar golf course on the assumption that a skinny spring-fed creek would keep cooperating forever.

And then, during the drought, instead of making peace with the one man who controlled the tap, they’d tried to choke off my well.

All right, I thought.

Let’s see how thirsty you can get.

I didn’t do anything rash. That’s another thing people misunderstand about farmers. We might be quick-tempered, but we can also be patient as fence posts, especially when it comes to revenge.

First, I made copies of everything. The original deed. The water agreement. The scattering of letters between Granddad and the county engineer from the ’70s. I scanned them to a flash drive and took paper copies to my lawyer, a quiet man named Alvarez who specialized in land disputes and had the patient demeanor of a Confessional priest.

He read slowly, lips moving silently as he traced the lines.

“Holy hell,” he said eventually, tapping the clause. “They built that whole course on this?”

“Appears so,” I said. “Nobody ever asked me to modify the agreement. The board minutes show they ‘repurposed existing ag infrastructure.’ Which is a fancy way of saying they freeloaded.”

He leaned back.

“You could move a lot of earth with this,” he said.

“Can I divert the creek?” I asked. “Legally. Put the water back on my fields.”

He considered.

“The agreement gives you control over flow at the entry point,” he said. “It requires you to maintain a ‘reasonable downstream allowance’ for existing agricultural users, which is what this network used to serve. But the course isn’t ag. It’s recreational. If you can demonstrate your livestock and crops require more water in drought than you’re currently taking, you can argue necessity.”

“And the HOA?” I asked.

“They’d scream, of course,” he said. “Probably sue. But given that they just illegally modified your barn and tried to restrict your well without a proper variance hearing, a judge might not be too sympathetic to their cries about dry fairways.”

I nodded slowly.

“What about the well ordinance?” I asked.

He smiled faintly.

“I pulled the latest version,” he said, sliding a stapled packet across the desk. “They pushed it through the water board after ‘concerned citizens’—read: Sagebrook—complained about rural wells. But there’s a carved-out exception for pre-1970 ‘primary ag wells’ whose usage supports livestock. That’s your well. They either didn’t realize or hoped you wouldn’t.”

“So they had no right to stick a restrictor on it,” I said.

“None whatsoever,” he said. “And the county knows it. They’re counting on you not knowing it.”

I felt my jaw tighten.

“How much trouble do I get into if I take a backhoe to that diversion box?” I asked.

He flipped through the documents again.

“If you reroute water to your fields and maintain minimal flow beyond your boundary as stipulated, you’re within your rights,” he said. “They might claim you’re endangering their investment. But they built that course at their own risk.”

“And the HOA?” I asked.

“I’d send them a certified letter first,” he said. “Remind them of your primary water rights. Put them on notice. When the sprinklers go dry, they can’t say they weren’t warned.”

I left his office standing taller, the weight of generations sitting on my shoulders but suddenly feeling less like a burden and more like armor.

Next stop was the county records office. I spent an afternoon in a fluorescent-lit room with a bored clerk digging through old plats, easements, and meeting minutes. The deeper I dug, the more I realized how much Sagebrook had relied on assumptions.

The walking trail that ran along my fence line, the one their residents strolled every evening with lattes and Labradors? Half of it sat on my side of the original property line. The developer had “rounded off” the trail to make the route more scenic, shaving ten feet from my pasture and never recording a formal easement.

The irrigation pipeline easement itself was drawn sloppy, a thick line on an old map that could be interpreted several ways. They’d laid additional lines and control boxes just inside my boundary for convenience.

Convenience was about to cost them.

Two days later, I rented a backhoe from the same place Sagebrook used when they prettied up their landscape. I signed the papers under my own name, smiled at the guy behind the counter, and hauled it home.

At dawn the next morning, I parked that yellow beast beside the old diversion box where the creek slipped into concrete. The metal grate was rusted in spots, the concrete stained with years of flowing water.

I stood there a moment, listening.

The dry whisper of brittle grass. The faint trickle of water. In the distance, the soft whoosh of sprinklers on the far side of the fence, still blissfully ignorant.

“Sorry, Granddad,” I murmured. “I know you liked the idea of helping neighbors. But these aren’t neighbors. These are leeches.”

I climbed into the backhoe and started it up. The engine growled, a hungry, familiar sound. I lowered the bucket and took the first bite of earth upstream of the box.

The soil gave way easily, dark and damp. I dug a trench parallel to the creek, curving it toward the low part of my pasture that had been dust for months. Each scoop of dirt I moved was a whispered rebuttal to every fine, every letter, every smug smile from Robin Matthews.

By mid-morning, sweat soaked my shirt. My arms vibrated with the machine. I shut off the backhoe and stepped into the trench, checking angles, making sure gravity was on my side.

Then came the moment.

I knocked a notch into the bank with a shovel, widening it until the creek’s edge began to crumble. Water lapped higher, then spilled over, a thin, eager tongue of muddy flow.

It slid into the trench and started to run.

I watched, chest tight, as that tiny stream became a trickle, then a steady ribbon. It coursed down the new channel, gleefully abandoning the concrete throat that had fed Sagebrook for years.

Downstream of the diversion box, the old creek bed shrank to a narrow ribbon. Enough to satisfy the “reasonable allowance” clause. Not enough to keep a golf course green in a drought.

I didn’t touch the box itself. Didn’t damage county infrastructure. I just… gave the water an easier path. One that happened to end in my haggard pasture instead of in their underground pipes.

When I turned my head, I could see the top of Sagebrook’s fountain over the fence, a tall spray that had been a constant presence in my peripheral vision. It still fanned into the air, droplets catching sunlight.

Give it a day, I thought.

I wasn’t done.

Along the outer edge of my property, the developers had laid a concrete walking path that meandered through scrub and along my fence line. It was a big selling point in their brochures—“miles of scenic nature trails.”

I’d always tolerated it. Even waved at the occasional jogger. But now that I’d seen the actual survey markers, I knew the truth: their “nature trail” cut a generous curve into my land.

That afternoon, I hauled fence posts, wire, and a post-hole digger out of my half-demolished barn. I followed the true property line, the one marked in faded rebar stakes and old survey tape, and drove T-posts into the ground.

On each post, I hung a sign. Big, reflective, impossible to ignore.

PRIVATE PROPERTY. NO TRESPASSING. NO EASEMENT GRANTED.

At the point where the trail crossed my line, I strung a gate and locked it.

I mounted a couple of motion-activated cameras on my side, pointed at the fence. Not because I was scared—they weren’t going to jump me with their tennis elbows—but because if they tried something, I wanted it on video.

By sunset, my pasture was drinking new water, and Sagebrook’s pipeline was sucking on air it didn’t yet know it had.

The next morning, my phone started buzzing before breakfast.

It wasn’t the HOA. Not yet.

It was my friend Darren, who worked maintenance at the course.

“Jake,” he said, voice half panicked, half delighted. “Did you do something to the creek?”

“Why?” I asked, feigning innocence as I watched my cows jostle for position along the fresher, muddier stretch of the rerouted stream.

“Fountain’s down,” he said. “Pumps are cavitating. We checked the intake screens, the filters—nothing. It’s like someone turned the volume down on the water.”

“Huh,” I said. “Must be the drought.”

“I saw your pasture,” he said. “Looks like it’s raining on just your side, buddy.”

I smiled.

“Guess I got lucky,” I said.

By noon, the sprinklers along holes three through seven were wheezing, heads popping up and hissing air with pathetic sputters. The tee boxes went dark. The thin topsoil, baked by weeks of sun, started to show beige patches between blades of grass.

Two days later, the fountain at the clubhouse shut off with a cough. The white noise that had been the soundtrack to every HOA brunch died, leaving an unnatural silence over their entry boulevard.

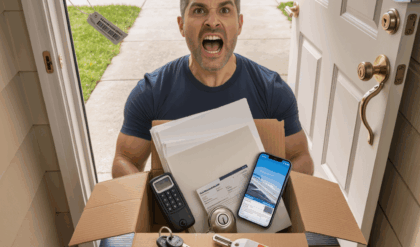

By the end of the week, my mailbox spit out certified letters like a nervous slot machine.

CEASE AND DESIST, one screamed, alleging that I was “unlawfully interfering with Sagebrook HOA’s lawful use of water.”

NOTICE OF INTENT TO SUE, another read, listing a parade of possible causes of action: tortious interference, negligence, endangering property values.

A third was from the county, more measured in tone, asking for a “meeting to clarify recent modifications to the waterway.”

I stacked them on the counter without opening them all the way. I already knew what they wanted.

The first direct confrontation came on a Saturday morning.

I was mending a gate near the front drive when a convoy of cars pulled up—three SUVs in a neat row, all shiny, all white. Out stepped Robin Matthews in a linen blouse and wedge sandals, flanked by two men in polos and khakis and expressions like sour milk.

The HOA board in full plumage.

“Mr. Miller,” Robin called, marching up to the fence like she was storming a castle. “We need to talk.”

I leaned on the gate and wiped sweat from my forehead with the back of my hand.

“Morning,” I said. “You folks lost?”

“You know exactly why we’re here,” she said. “Our water pressure has dropped. Our fountain is off. Our golf course is dying. Residents are furious. This is unacceptable.”

“Sounds rough,” I said.

Her eyes narrowed.

“You’ve diverted the creek,” she said. “We saw the trench. You can’t do that.”

“I sure can,” I said. “Got the signed agreement in my kitchen to prove it. Primary control of flow belongs to the landowner. That’d be me.”

“That agreement was for agricultural use,” one of the men—a lawyer, judging by the way he held a leather portfolio like it was a shield—said. “The course is classified as recreational ag.”

“Cute,” I said. “Except the amendment that changed your use classification never went through the proper channels. You repurposed an ag line for non-ag use without modifying the underlying rights. That’s not my problem. That’s yours.”

Robin’s face flushed.

“You are harming our community,” she said. “Property values are dropping. We have brown spots on the fairways.”

“I had a missing barn wall,” I said. “Funny, I don’t recall you weeping about my property value.”

“That was a safety issue,” she snapped. “Your barn posed a visual and structural hazard.”

“It posed a view you didn’t like,” I said. “So you leaned on some county friend to sign a bogus order. You trespassed. You damaged my property. And now you’re panicking because I stopped being your unknowing water charity.”

Her jaw clenched.

“You’re being petty,” she said. “Childish. We’re prepared to litigate if you don’t immediately restore the creek to its previous path.”

I straightened, wiped my hands on my jeans, and looked her dead in the eye.

“You want your water back?” I asked. “We can talk. But we’re not starting with the creek.”

“Where, then?” she asked, wary.

“With my barn,” I said. “And my well. And every fine and threat you’ve sent my way. You fix those, we negotiate a lease on the water. You keep pretending I’m some bumpkin you can steamroll, we see how far your dry golf course gets you.”

She laughed, a sharp, disbelieving bark.

“You think you can dictate terms?” she asked. “Our lawyers will eat you alive.”

I nodded toward the house.

“Got a better lawyer eating breakfast in there,” I said. “And a file full of documents your high-priced counsel apparently never bothered to read. You’re standing on my side of the line, Ms. Matthews. Legally and literally. Step back before you get dizzy.”

One of the men touched her arm, murmured something low. She shot him a look, then turned back to me.

“You’ll be hearing from us,” she said.

“I look forward to it,” I replied.

They left in a huff, SUV tires spitting gravel. As they turned out onto the road, I caught a glimpse of the course through the gap in the trees.

Stripe patterns that had been emerald last month now looked tired. The practice green by the clubhouse had a faint yellow tinge. Golfers—those who hadn’t cancelled their memberships yet—stood around murmuring, putters in hand, staring at cracks in the ground that had never been there before.

It was a beautiful sight.

But I knew better than to gloat too soon.

HOAs don’t go down easy. They go down swinging.

Part Three

Lawsuits are like droughts—they drag on, drain everything around them, and make everyone cranky.

The first volley from Sagebrook was a thick envelope hand-delivered by a pale young process server who looked like he’d rather be anywhere else. The complaint inside was twenty-eight pages long and full of phrases like “malicious interference” and “intentional infliction of emotional distress.”

Emotional distress. Over grass.

My lawyer, Alvarez, read it with a pen in hand, annotating the margins until the pages looked like they’d been in a knife fight.

“They’re throwing spaghetti at the wall,” he said finally. “Half of this is bluster. The other half is… creative. They’re hoping you’ll fold before it gets expensive.”

“I’m not folding,” I said.

“Good,” he said. “Then we go on offense.”

He filed a countersuit: trespass, property damage, attempted interference with grandfathered water rights, harassment. He attached photographs of my torn barn, the county’s illegal well notice, and a copy of the water agreement with Granddad’s name circled in blue ink.

The first hearing was held in a bland courtroom with buzzing fluorescent lights and pews that smelled like disinfectant. On one side of the aisle sat me, Alvarez, and Dr. Henderson—who’d agreed to testify about the structural integrity of my barn and the sudden interest the HOA had taken in my health records when they started sniffing around for that competency angle.

On the other side sat Robin and the HOA board, flanked by two attorneys in suits that probably cost more than my truck.

The judge, a woman with tired eyes and a no-nonsense bun, listened as each side laid out their grievances.

“This man has crippled an entire community’s water supply over a personal vendetta,” Sagebrook’s lawyer drawled, gesturing toward me like I was some rabid possum.

“This association has repeatedly overstepped its bounds, illegally entered Mr. Miller’s property, damaged his structures, and attempted to steal his water while wasting the community’s on non-essential luxuries,” Alvarez responded calmly.

When Alvarez brought up the original 1962 agreement, the judge leaned forward.

“You’re saying the HOA’s entire irrigation system depends on a pipeline whose primary control rests with Mr. Miller?” she asked.

“That’s correct, Your Honor,” Alvarez said. “They never secured a modification of rights. Mr. Miller has generously allowed the water to flow for years without asking for compensation.”

The judge turned to Sagebrook’s counsel.

“Is that accurate?” she asked.

The attorney shifted.

“Your Honor, the county approved the use of the existing infrastructure,” he said. “We proceeded under the assumption—”

“The assumption that no one would read the fine print,” the judge cut in. “Well, someone has. I’m not issuing any injunction forcing Mr. Miller to restore the water flow at this time.”

Robin made a strangled noise.

“But Your Honor,” she burst out, unable to contain herself, “our grass—”

“Is not a constitutional right,” the judge said sharply. “What you have is a contract problem. You built a water-dependent amenity on a tenuous arrangement. That’s not Mr. Miller’s fault.”

Alvarez hid a smile behind his legal pad.

“As for the barn,” the judge continued, turning a frosty gaze toward the county rep in the back row, “I’m troubled by the manner in which Code Enforcement acted. Demolishing a portion of a structure on private land without a proper hearing? That smells wrong. We’ll be looking into that separately.”

By the time we walked out, the scoreboard read something like: Jake 2, HOA 0.

Outside the courthouse, a cluster of Sagebrook residents had gathered. They were easy to spot—khaki shorts, polo shirts, visors. A few held signs scrawled hastily in marker:

SAVE OUR COURSE

HOA BOARD OUT

As Robin emerged, they swarmed.

“What happened in there, Robin?” a man in mirrored sunglasses demanded. “We’re losing tee boxes by the week. My backyard looks like a hayfield.”

“You told us you had this handled,” a woman with a perfectly highlighted bob said. “Now we hear our entire water source depends on some farmer you’ve been harassing?”

“Please, everyone, calm down,” Robin said, plastering on her practiced smile. “We’re exploring all legal options.”

I watched from the shade of a live oak across the street. Some of the residents noticed me, eyes flicking in my direction, faces twisted with a mix of curiosity and resentment.

Darren, my maintenance friend, elbowed through the crowd to reach me.

“You’re the devil and a hero in there,” he said. “Half of them want to sue you personally. The other half want your autograph.”

“I’ll settle for them wanting a new board,” I said.

“Give it a week,” he replied. “The Facebook group is already a dumpster fire.”

He wasn’t kidding.

That night, my niece showed me screenshots from Sagebrook’s private residents page, which had leaked faster than a cheap inflatable pool.

WHO APPROVED THIS GOLF COURSE WATER DEAL???

So let me get this straight: our HOA picked a fight with the man who controls our tap? GENIUS.

Maybe if we spent less money on flowers at the gate and more on legal counsel we wouldn’t be in this mess.

Someone had posted a drone shot of the course, brown patches spreading like a fungus across fairways that used to be emerald.

In the comments, people were tagging Robin, demanding answers.

She was conspicuously silent.

One post, buried in the thread, caught my eye.

As a farmer’s kid, I have to say: you don’t tear down someone’s barn and mess with their well, then expect them to keep your grass green out of the goodness of their heart.

It wasn’t long before rumors started trickling back to me.

An emergency HOA meeting. A petition for recall. Words like “mismanagement” and “dereliction of duty” being thrown around in voices that used to coo over charcuterie boards at the clubhouse.

A week later, I got confirmation.

Darren called, barely containing his glee.

“They canned her,” he said. “Robin’s out. Half the board resigned. They appointed an interim president who actually owns jeans.”

“Progress,” I said.

A few days after that, a different SUV pulled into my drive. Less shiny. Mud on the tires. From it stepped a man in his late forties in a ball cap, followed by a woman in a t-shirt with the Sagebrook logo faded from too many washes.

“Mr. Miller?” the man asked, stopping at the gate.

“That’s me,” I said.

“I’m Mark Jensen,” he said, sticking his hand through the bars. “New HOA president. This is my wife, Linda. We live on the ninth fairway. Or what used to be a fairway.”

I shook his hand. His grip was firm, his palm calloused. Not the usual HOA texture.

“I didn’t vote for any of the crap that went down before,” he said. “I’ve been at board meetings raising hell for months. They finally had enough people fed up to force a change.”

“Congratulations,” I said. “My sympathy.”

He huffed a laugh.

“We’re not here to threaten,” Linda said quickly. “We’re here to apologize. And to ask if you’d be willing to talk.”

“Talking’s free,” I said. “Water isn’t.”

They exchanged a look.

“Fair,” Mark said. “Can we come in?”

We sat at my kitchen table, the same scarred wood where I’d played dominoes with Granddad and signed the papers that put my name formally on the trust and the land.

Linda turned her coffee mug between her hands.

“I’m sorry,” she said abruptly. “For what they did to your barn. For the fines. For the way they treated you like a problem instead of a neighbor.”

“They?” I asked.

She winced.

“We,” she corrected. “We let it happen. Even if we didn’t sign the papers, we benefited from the bullying. Cheap water, green lawns, someone else paid the price.”

I studied her. She meant it. Or at least, she was trying to.

“Why do you care now?” I asked.

She looked out the window, toward where the course’s treeline began.

“Because my son asked me why the grass is dead,” she said. “And I realized the only honest answer is: because we cared more about appearances than doing right by the people who were here first.”

Mark cleared his throat.

“We’d like to make things right,” he said. “We can’t undo everything, but we can start.”

He slid a folder across the table.

Inside was a proposal drafted in less legalese than I’d expected. They’d worked with their attorney, sure, but the gist was clear.

They wanted a water lease.

Twenty-five years, paid upfront. They’d agree to a fixed annual volume, with reductions during drought to protect my usage first. In return, they’d rebuild my barn to my specifications, cover all legal fees, pay damages, and sign a binding non-interference agreement regarding my well and land.

If they—or any future board—touched my property without consent, the lease would terminate immediately, and I’d be entitled to punitive damages.

It was… more generous than I’d imagined.

“Where’d this sudden humility come from?” I asked.

Mark grimaced.

“You haven’t seen the balance sheets,” he said. “We’re bleeding. Memberships down. Lawsuits from residents. Our insurance premiums shot through the roof after the barn stunt made the papers. If we don’t fix the course, half the people will bail. If we try to drill a new well, the county will drag us through environmental reviews for years.”

“You built your paradise on borrowed water,” I said. “Now the lender’s calling.”

“We know,” Linda said softly.

I tapped the proposal with one finger.

“I’m not signing anything that leaves you a chance to pull another fast one,” I said. “I want a seat on the water conservation committee. I want veto power on any ordinance that touches private wells or creek use within three miles.”

Mark blinked.

“You want to be part of our HOA?” he asked.

“I want a say whenever someone in a collared shirt decides they know better than the people who dig postholes,” I said.

He considered, then nodded slowly.

“I can sell that,” he said. “Frankly, we could use someone who gives a damn about something other than mailbox colors.”

Linda smiled faintly.

“What about the trail?” she asked, a little hopeful. “Our kids miss it. They used to ride their bikes along that loop. We can redraw it properly, get a recorded easement, maintain the fencing—”

I held up a hand.

“You close the books on the past, we’ll talk about opening gates in the future,” I said. “But not yet.”

They both nodded.

Alvarez reviewed the proposal, sharpened the terms, added a clause that made me grin: any attempt by the HOA to levy fines, restrictions, or enforcement actions on my property without cause would trigger a doubling of their annual water fee.

We signed in a conference room at the bank, pens scratching on thick paper. Two notaries stamped and initialed.

The day their check cleared—enough to pay off my remaining equipment loan, rebuild the barn, and stick a comfortable sum into a contingency fund—I drove out to the diversion box.

The trench I’d dug still carried the creek’s flow to my pasture, but the concrete throat now sat mostly dry. A few stray weeds had sprouted in the damp cracks.

I opened the valve my grandfather had installed decades ago—a simple metal gate in the concrete—and let a portion of the water slip back into the pipe.

Not all of it. Never all.

Just enough to make their sprinklers cough, then wheeze, then sputter back to life at half strength.

The next day, from the rise behind my house, I watched the course.

Where there had been brown, there was now streaky green. Patches. Imperfect. A reminder that lushness was no longer their birthright. It was leased. Contingent.

On me.

I rebuilt the barn with my own two hands and the help of a crew from town. We left the old, splintered boards in a pile nearby, a monument to the day someone thought they could tear down a Miller building and walk away.

On one of the new beams, up in the loft where only I and a few barn cats ever went, I carved a date.

The day they learned whose land this really was.

The HOA didn’t vanish. They still sent out newsletters about mailbox maintenance and paint color palettes. But there was a new tone in their emails—less command, more suggestion.

At board meetings, Mark pushed for changes. Less focus on cosmetic infractions. More on actual safety and community.

Every quarter, I attended the water committee meeting. I sat at their conference table in my boots and flannel, listening to proposals about xeriscaping, native plants, and tiered pricing for excessive use.

When someone floated the idea of “limiting agricultural wells further during future droughts,” I cleared my throat.

“Over my dead body,” I said mildly.

The motion died without a second.

Funny how that works.

Word of what happened spread beyond Sagebrook. I started getting calls from other rural landowners, asking about water rights, about old agreements, about standing up to HOAs.

I told them what Granddad told me: read the fine print. Know your land. Don’t let anyone with a clipboard and a confident smile talk you out of what your grandparents sweated to secure.

Sagebrook’s residents adjusted. Some sold and moved to places where HOAs were more ruthless, if that was possible. Others put in native grasses, embraced the mottled look, bragged to their friends about being “water-conscious.”

Darren sent me a picture one afternoon of a sign they’d put up near the first tee:

PLEASE BE PATIENT WITH COURSE CONDITIONS. WE ARE COMMITTED TO RESPONSIBLE WATER USE IN PARTNERSHIP WITH OUR NEIGHBORING FARMS.

Underneath, someone had drawn a little cartoon cow with sunglasses.

I printed the photo and taped it to my fridge.

The threat of them taking my land never fully evaporated—not in a world where developers could spin straw into gold with enough backing. But it receded, like a bad storm moving past.

They’d wanted to turn my place into an extension of their manicured paradise. Instead, they ended up paying me to keep their paradise from turning into a dust bowl.

I’d say that was a fair trade.

They banned my well water on paper.

I dried out their golf course in reality.

And we all learned a new way to live with each other, one that started with a simple, hard truth:

You don’t bite the hand that holds the tap.

Part Four

Years have a way of sanding down sharp edges, but some days still feel carved in stone.

Ten years after the creek diversion, Sagebrook didn’t look like the glossy brochure that used to litter their sales office. It looked… better.

They’d given up on keeping every inch of turf neon green. The fairways were narrower, framed by native grasses that swayed golden in the evening light. Mesquite and live oaks left standing during development had been joined by new plantings—native, hardy species whose roots dug deep instead of sipping constantly from the surface.

The walking trail, after much legal paperwork and surveying that actually respected the line, snaked properly through their land. On my side, I’d built my own dirt track along the fence. Sometimes, on cool mornings when no one could see, I’d time my walk so that I and some Sagebrook jogger ended up in parallel, twenty feet apart, two lives moving in sync without intersecting.

The golf course installed a small gray sign on each tee box:

WATERED WITH 40% LESS THAN PRE-2018 USE. THANKS FOR HELPING US CONSERVE.

It was marketing, sure. But it was also true. My lease terms saw to that.

I didn’t attend many of their events, but I made an exception one fall when Mark invited me to a “Community Appreciation Day” at the clubhouse.

“We’re doing a little recognition ceremony,” he said on the phone. “For partners. Vendors. People who helped us survive the drought years.”

I almost said no. But something in his voice—earnest, a little worn—made me reconsider.

I wore clean jeans and a shirt that didn’t have feed stains and walked into a clubhouse I’d only ever seen from the outside. The interior was all dark wood and soft lighting, walls lined with photos of tournament winners and charity check presentations.

On a back wall, between a photo of the groundbreaking and one of a ribbon-cutting, hung a new frame: a picture of my creek, dappled in sunlight, with a small plaque beneath.

In appreciation of the Miller Family,

Stewards of the land we are privileged to share.

I snorted softly.

“Stewards,” I murmured. “That’s one way to say ‘guy who almost turned your 7th hole into a dust bowl.’”

During the ceremony, they recognized vendors, maintenance staff, committee volunteers. Then Mark took the mic.

“There’s one more person we owe,” he said, scanning the room. “Someone who reminded us, the hard way, that we don’t live in a bubble here.”

He gestured toward me.

“Jake, you mind?”

I gritted my teeth and made my way to the front, feeling eyes follow me. Some were curious. A few were still bitter. Most were simply interested, ready-made audience for any spectacle.

“This is Jake Miller,” Mark said. “His family has been here longer than all of ours put together. When we first moved in, our HOA treated his land like a backdrop. A problem. Something to be managed.”

He paused.

“It was wrong,” he said. “And we paid for it. Literally and figuratively.”

A few chuckles rippled through the crowd.

“But Jake did something we didn’t deserve,” he continued. “He didn’t just punish us and walk away. He forced us to change. To rethink how we use water. How we treat neighbors. How we measure value.”

He handed me the mic.

“You want to say something?” he asked.

No. Every cell in my body said no.

I thought of Granddad, of the dusty office, of that note on the old deed.

Follow the water.

I looked out at the room. At Linda in the front row. At Darren leaning against the wall. At some of the same faces that had glared at me outside the courthouse years ago.

“Your grass looks better now,” I said.

They laughed.

“And I don’t just mean it’s greener,” I added. “I mean it looks like it belongs here. Like it’s part of Texas, not a photograph you taped over it.”

I shifted, feeling the weight of a hundred eyes.

“I didn’t divert that creek because I hate all of you,” I said. “I did it because I refuse to let anybody—developer, board, whoever—act like the land is a stage for their show.”

I gestured toward the window, where the course rolled away under a blue sky.

“This land has a memory,” I said. “It remembers before the cart paths and the fountains. It remembers when those fairways were pasture and when even before that, they were prairie. You built your homes here. I don’t begrudge anyone a roof. But if you’re going to live here, you have to respect what came before you.”

Silence. The kind that comes when people know you’re not just talking about trees and grass.

“The well they tried to cap?” I said. “My grandfather dug that with a backhoe older than some of you. He watered cows, not putting greens. When the county tried to tell me how much I could draw while letting this place pump like it was a river, that wasn’t conservation. That was politics.”

A murmur. A few nods.

“I pushed back,” I said. “I don’t apologize for that. But I’m glad some of you pushed back, too. On your own board. On your own assumptions.”

I handed the mic back to Mark.

“That’s all I’ve got,” I said.

Afterward, people came up one by one. Some just nodded. A few apologized. Others wanted to tell me about the native plants they’d put in, or how their kids learned in school about aquifers and now lectured them on shorter showers.

One older man, sunspots on his forehead and a faded Marine Corps cap in his hands, shook mine firmly.

“My daughter’s a lawyer,” he said. “HOA law. When this all went down, she told me we were idiots. Said if she represented you, she would’ve gone for the jugular.”

I smiled.

“I had a soft spot,” I said. “For your grounds crew.”

He chuckled.

“Sometimes mercy is better,” he said. “Don’t tell my daughter I said that.”

On my way out, a boy of about ten trotted up to me, breathless.

“Mr. Miller?” he said.

“Yeah?”

“You’re the farmer, right?” he asked.

“That’s me,” I said.

“My science teacher says we’re in a megadrought,” he said. “That we should be more like you. She showed us pictures of your creek and your fields. I thought that was cool.”

I blinked.

“My creek made it into a classroom?” I asked.

He nodded.

“Yeah, she said, ‘Some people think water just comes out of pipes. But it starts in places like this. From people who take care of it.’”

I swallowed.

“Tell your teacher thanks,” I said. “And drink from the tap, not plastic bottles.”

He grinned and ran back to his parents.

As I walked back to my truck, I glanced toward my property. The barn stood solid, red paint starting to fade just enough to look honest. The windmill we’d installed last year spun lazily, supplementing the well pump with a bit of old-fashioned power.

The creek—my creek—glittered in the distance, its path now part memory, part strategy.

I thought, for a moment, about how easily this story could have gone differently. If I hadn’t found that deed. If I hadn’t had a decent lawyer. If the judge had been more impressed by golf shoes than boots.

Developers might’ve carved up my land for more houses. My well could’ve been capped. The barn bulldozed completely.

The farm would have become a cul-de-sac named something insulting like “Miller’s Meadows,” with a plaque at the entrance telling some sanitized version of our history.

Instead, the farm was still a farm. The golf course was still a golf course, albeit a more honest one. And between us ran not just a fence and a creek, but an uneasy, hard-earned understanding.

HOAs, I’d learned, are only as powerful as the people who don’t push back.

And sometimes, all it takes to topple an empire of neat lawns and petty fines is a man with a backhoe, a file of old papers, and a refusal to be told when he can water his own damn cows.

The years softened my anger toward Robin, even. Last I heard, she’d moved to a different development in a different state, one where the homeowners were less likely to revolt. Maybe she learned something. Maybe she didn’t.

But every time I drove past the clubhouse and saw that plaque with my family name, I smiled.

Not because I liked the attention.

Because I knew, deep down, that it wasn’t about me at all.

It was about what Granddad had written in that note.

If they ever get too big for their britches, follow the water.

I had.

And it led all of us somewhere better than where we started.

Part Five

If you stand under the old pecan tree on my property and look east, you can see four layers of time all at once.

Closest is the barn, rebuilt and weathered, its new boards grayed to match the old. Beyond that, my fields, stitched with irrigation lines that carry the creek’s gift to where it’s needed most. Past them, the golf course rolls gently, no longer a bright scar but a softer patchwork of green and gold. And beyond that, on a clear day, you can just make out the shimmer of the river that all this water eventually reaches.

Sometimes I stand there at dusk with my granddaughter on my shoulders, and I point.

“That’s ours,” I tell her, nodding at the house and barn. “That’s theirs,” I say, pointing at Sagebrook. “And that”—the creek, winding like a silver ribbon—“belongs to all of us if we don’t screw it up.”

She’s five. Her main concerns are whether she can keep a frog she found and if we’re having pancakes in the morning. But she listens anyway, big eyes tracking my finger.

“Why did they break your barn?” she asked me once, out of nowhere, while we were tossing pebbles into the shallows.

I thought about the easiest answer. They were mean. They were bad.

Instead, I told her the truth.

“They were scared,” I said. “Scared of losing control. Scared of things they couldn’t change. Sometimes when people are scared, they look for something to push around. Makes them feel big again.”

“Did it work?” she asked seriously.

“For a while,” I said. “Then they pushed the wrong person.”

She giggled.

“You?” she said.

“Me,” I agreed.

She considered that, then nodded sagely.

“I won’t let anybody push my barn,” she said.

“Good girl,” I said.

The county, in its own slow way, learned from the fiasco. They tightened rules, sure, but not just for wells. For developers. For HOAs. New ordinances required clearer water use agreements, stricter review of any plan that leaned on “existing infrastructure.”

Sometimes I get invited to speak at those meetings. Not as a plaintiff or an angry citizen, but as “a stakeholder in the watershed.” That title still feels weird on my tongue, but I wear it.

I tell them what I told Sagebrook. Water remembers. You can pipe it, bottle it, spray it over eighteen holes, but it comes from somewhere, and someone has to live with what you do to it.

The farm changed, too. Forty acres went into a conservation easement, ensuring no developer could ever subdivide the heart of it. We diversified—added a small orchard, a pumpkin patch that kids from both sides of the fence visit every fall. Sagebrook’s HOA even sponsors a “Farm Day,” bussing in kids in polos and light-up sneakers to pet goats and stare in horror as chickens flap past.

“Smells weird,” I overheard one boy say once, nose wrinkling.

“That’s what real life smells like,” his mother replied. “Breathe it in.”

I almost hugged her.

Sagebrook got a little less Sagebrook, too. Some rules relaxed. holiday decorations no longer earned citations unless they were a genuine fire hazard. People put raised beds in their backyards, growing tomatoes and peppers where only ornamental shrubs had been.

Once, as I was loading feed bags into my truck at the Co-Op, I saw a familiar face: a man who’d yelled the loudest at that courthouse rally years ago, furious about his fading lawn.

He gave me a tight nod.

“Got one of those rain barrels you talked about,” he said. “Feels good, using what falls on my own roof instead of sucking it from the ground.”

“Welcome to the club,” I said.

He hesitated, then stuck out his hand.

“Sorry I called you a psycho farmer on Facebook,” he said.

I shook his hand.

“I’ve been called worse,” I said.

On the day the 25-year water lease was renewed—Sagebrook’s board voting unanimously to keep things as they were instead of rolling the dice on a new well plan—I dug that old file box out again.

The paper was more fragile now, the ink more faded. Granddad’s note still clung to the top with determined tape.

If they ever get too big for their britches, follow the water.

I added a note of my own, written on a fresh yellow sticky.

If you ever think you’re the only one who matters, stand at the creek and look both ways. – J.

Then I put the lid back on and slid the box into a cabinet my daughter had installed in the office, behind neat rows of labeled binders: WATER LEASE, CONSERVATION PLAN, HOA AGREEMENTS.

Life went on. Droughts came and went. Some years were lean, others generous. Storms flooded the creek, trees fell, fences broke. Babies were born. Old men died. The barn roof leaked and was patched and leaked again. The well pump groaned and was replaced with a more efficient model that made Granddad’s old one look like a museum piece.

Through it all, the HOA remained what it always had been at its core: a group of people trying to live together without driving each other insane. Sometimes they succeeded. Sometimes they sent an email about trash cans being visible from the street that made even the new president roll his eyes.

But they never again told me when I could water my land.

They never again sent a crew to my property without a signed agreement and a phone call.

They never again forgot that every green blade of their golf course depended on a stream that ran through my pasture first.

When I’m gone, most of this will fall to my daughter and, eventually, to that frog-loving granddaughter of mine.

She’s already got the stubborn streak. When the HOA suggested turning part of my field into overflow parking for a charity tournament, she, at eight years old, looked the president dead in the eye and said, “No way. That’s cow territory.”

I don’t worry about her.

She’ll have the deeds, the water rights, the stories. She’ll know where the line is, both on paper and in her gut.

And if some future board forgets?

Well.

There’s an old backhoe in the barn, a creek that still remembers how to move, and a family note taped to a file that has survived longer than any golf course ever will.

They banned my well water.

I dried out their golf course.

In the end, the real victory wasn’t that their fairways went brown.

It was that everyone learned the same lesson:

You can build gates. You can write bylaws. You can hold meetings where you argue about the shade of a front door.

But you don’t get to rewrite the past.

And you sure as hell don’t get to tell the land who it belongs to.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.