HOA Karen Fined Me for Noise—She Froze When Police Proved I Wasn’t Home!

Part 1

The citation was taped to my door like a warning from a vengeful god: duct tape in a crosshatch so thick it looked like someone tried to seal a crime scene shut. In angry red letters, it screamed: $500 FINE — EXCESSIVE NOISE VIOLATION — THURSDAY 3:17 A.M.

I stood in my driveway still holding my shuttle receipt from PDX, suitcase wheels imprinting damp half-moons on the concrete, and tried to line up reality with the timestamp. Thursday at 3:17 a.m., I was thirty thousand feet above Kansas in seat 12C, wedged next to a kindly grandmother who told me her grandson’s Little League batting average while a flight attendant buckled a belt none of us ever forget how to use. My conference badge still hung from the zipper of my laptop bag: Emerald City Cyber 2025. My boarding passes were crisp inside the pocket, my phone stuffed with airline emails and TSA alerts. I could prove where I was. I could prove where I wasn’t.

And yet here it was: a fine in red ink and fury.

Margaret Whitmore had finally lost her mind.

If you’ve never met a suburban dictator in a blazer with her name embroidered in gold thread, allow me to introduce our HOA president. Margaret ran Maple Ridge Estates like a personal duchy. She was sixty-three, hair sprayed into a helmet that could deflect hail, and a smile that ended exactly at her teeth. She had once measured a neighbor’s fence with a laser level, then mailed a violation because it exceeded the allowed height by “the thickness of a credit card.” She fined the Johnsons because their seven-year-old’s chalk drawings constituted “unapproved art.” She pushed through an odd-number rule for flower groupings in a late-night meeting where only two people knew what was being voted on.

Before she became our tormentor, Margaret had been a mid-level bank manager until a hush-hush separation that smelled like complaints no one could print. She redirected the need to control into volunteer power and never looked back. She converted her garage into “HOA Headquarters”—a folding table, two dented filing cabinets, and a whiteboard where she tracked infractions with color-coded markers like a sitcom villain with a murder wall. Her business cards read: PRESIDENT & CHIEF COMPLIANCE OFFICER, MAPLE RIDGE ESTATES, as if ~150 homes and a retention pond required a compliance regime.

She especially disliked what she called “unattached males.” Her theory—never burdened by evidence—was that we lowered the “family-friendly atmosphere,” attracted “unsavory elements,” and probably ran “secret gambling rings” in the basement. My basement had a treadmill and five banker’s boxes of tax returns, but explaining nuance to Margaret was like explaining encryption to a houseplant.

The more I stared at the citation, the more a heat rose in my chest that wasn’t just anger. It was the knowledge of pattern. In eight months she’d cited me for a hummingbird feeder (“encouraging pests”), left a warning for leaving my garbage cans at the curb for thirty-eight minutes (“visual pollution”), and suggested—at a public meeting with a microphone—that perhaps “unmarried residents” should pay higher HOA dues because “they use more resources.” When I asked which resources, she said “vibes” and moved on. She had tried to implement a dress code for checking the mail. A curfew for single adults. “Guidelines for visible masculinity.” You think I’m kidding, but I have the meeting minutes.

Inside my house, I dropped my bag and went straight to the evidence. Cybersecurity is my day job and my reflex. I pulled footage from the smart doorbell. Between 6:00 p.m. Wednesday—when my neighbor collected my mail—and 7:00 a.m. Thursday—when the paper flopped against the driveway—the camera saw nothing. No motion alerts. No lights. No parade of industrial music and hooligans. My backyard cameras agreed. The fiber internet kept logs like a diary. The router’s device connections were a flat line. The thermostat’s eco-mode never left its winter trench.

And then I found it: 3:05 a.m. Thursday. Night-vision gray. Margaret’s gray hair and HOA blazer smudging across my lawn like a uniform ghost. She stepped into frame just left of my front window holding something big and rectangular. She crouched like a burglar in a training video and leaned the object against the siding. For four minutes she lingered just beyond the glass, turning her head as if listening for witnesses.

At 3:15 a.m., the audio spiked—heavy metal through a portable speaker, the kind designed to survive a pool party. Not from inside my house. From outside. A two-minute-and-thirty-second blast of double-pedal drums and shredding guitar, the ridiculous, perfect specificity of someone who thinks “industrial music” sounds like a guy with a beard and a synesthetic grudge. At one point she looked directly into the doorbell lens, not realizing night vision doesn’t care about darkness. The camera kissed her with clarity: Margaret’s face, Margaret’s blazer, Margaret’s portable speaker. Margaret, official, unlawful, absurd.

I downloaded the clip to a flash drive and printed my itinerary, boarding passes, hotel receipts, and the conference badge. Then I drove to the precinct with a travel mug that said TRUST ME, I HAVE A HASH FUNCTION.

Officer James Bradley was the kind of cop recruiting posters pretend all cops are. Late thirties, steady posture, a face that listened. He watched the video twice, pressed his lips together, and then asked to see the boarding passes. “You were airborne at 3:17,” he said, tapping the timestamp with a capped pen. “Looks like your neighbor created the noise she reported.”

“Neighbor” was a kind word.

He agreed to come with me.

Margaret answered her door wearing the blazer, because of course she did. She’d embroidered her name over the breast like a victory patch you might get for surviving eight seasons of HOA Survivor. Her smile flickered when she saw the uniform beside me.

“Officer,” she said. “I’m so glad you’re here. We’ve had multiple complaints about industrial music and shouting from Mr. Pierce’s property. The standards in Maple Ridge—”

“What documentation do you have of these complaints?” Officer Bradley asked, mild. He had the tone of someone taking a statement in a hospital room.

Margaret’s cheeks became roses. “Verbal. Many are too intimidated to text. I did not want to create panic.”

“Did you happen to be on Mr. Pierce’s lawn last night?”

“I was investigating suspicious activity,” she said, quick as breath.

“Before or after the noise started?” I asked. “Because your citation says 3:17. You were on my lawn at 3:05.”

We played the video. When her face met its night-vision twin, she went so pale I thought she might faint into her azaleas. “Someone else must’ve put that speaker there,” she said, words tripping over each other. “I was responding to a complaint.”

“You own a portable speaker?” Officer Bradley asked.

“No,” she said. “Well, yes, for emergencies. It was stolen last week. I’ve been too busy with HOA duties to file a report.”

Officer Bradley did not sigh. It was a small miracle. “How did you know Mr. Pierce was at a conference?” he asked.

Silence. The kind with shape. “Lucky guess,” she said.

“You earlier called it a conference,” I said. “Specific word.”

“I overheard it,” she said. “At the grocery store. Someone mentioned…the thing.”

“What thing?” Officer Bradley asked.

She adjusted the blazer like she could put authority back on with a tug. “Even if he wasn’t home, he’s responsible for his property. Someone was there. People like him—single men—bring down the neighborhood. Someone has to maintain order.”

I recorded the rest. At first, it was just to preserve the absurdity. Then it turned into evidence. The longer she spoke, the louder she became. She called me a “permanent problem” and “the tip of a spear.” She accused me of hosting gambling nights with “women of low-moral TikTok.” She ranted about noise and compliance and “spirit of guidelines” while the officer’s pen made neat little notes. And then she made the mistake you wait for in depositions and in life.

She admitted she’d been monitoring my travel schedule through a friend at the airline.

Officer Bradley wrote one extra line after that. Then he looked up and said he’d be filing a report for harassment and false complaint. Margaret said words that couldn’t be reprinted in the HOA bylaws, and for the first time in many months, I laughed without guilt.

It wasn’t only the $500. It was the principle. And it was not just mine.

The next seventy-two hours were a chorus of doorbells and text threads and inbox pings. I was the neighborhood’s confession booth. Once someone says the truth out loud, the room loosens.

David Park told me about a broken-window violation issued while he was deployed overseas. The Andersons showed me fines for cars that weren’t theirs. Jennifer Santos held up a copy of a citation for “inappropriate curtains”—the exact same brand and pattern Margaret had in her china room. Robert and Susan Phillips, married sixty-one years, told me through tears about the $800 “hazardous medical equipment” fine for the wheelchair ramp on their porch. When they explained Robert’s stroke, Margaret had said illness was not an excuse for “poor sightlines.” She suggested moving to assisted living to “meet community standards.” Susan had paid because fear feels like gravity when you’re old.

Marcus Thompson, an EMT and Iraq veteran who works nights, had been fined for parking his car in his own driveway during the day. Margaret had proposed a rule—vehicles gone between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. on weekdays—because “most people are at work.” She said the spirit mattered more than the letter. Marcus showed me the letter of the law; it did not contain “spirit.”

Fourteen of us pooled money and hired an HOA-law specialist whose website looked like a bad ad but whose eyebrows lifted into something like joy when he saw our folder. His name was William Haworth, but everyone called him Hawk. He grinned like a hawk who had spotted a rabbit limping across open ground.

“This,” he said, flipping through the printouts, “is not merely an HOA problem. This is a legal buffet.”

Part 2

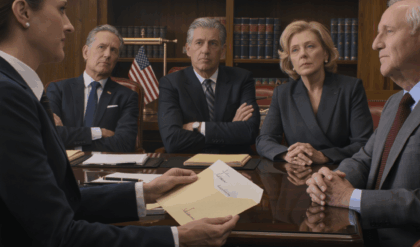

The emergency HOA meeting felt like a church potluck where everyone brought receipts instead of casseroles. Margaret sent out a newsletter the day before warning about “malcontents and destroyers of community values” and urging “all right-thinking members” to attend. People came. The community center’s folding chairs filled until they creaked. Neighbors pressed against walls. Someone stacked toddlers on a couch. The air had the crackle of a thunderstorm you can smell before it arrives.

Margaret took her seat at the head table, flanked by two board members who had learned long ago how much of their own reputations they were willing to auction to stay close to power. Her gavel waited like a weapon. She wore the blazer. Of course she wore the blazer. She was even wearing a small flag pin, which I don’t think she owns for any reason except to pin it on when she wants visual righteousness.

“My fellow homeowners,” she began, “it has been my honor to serve—”

Hawk stood.

He did not speak in thunder. He spoke in case law.

He put a stack of documents on the table that made the gavel look like a toy. He began at the beginning: twenty-three false complaints in eighteen months. Ten involving noise from vacant houses. Six alleging violations of rules that did not exist. Seven directed at “unattached” residents—five men, two women—who had received a disproportionate share of warnings, fines, and public shaming. He pointed to statutes. He slid copies of emails across the table—Margaret’s own words, forwarded by; pick an adjective: disgusted, exhausted, vindicated.

“Over sixteen thousand dollars in fines appear in the HOA ledger,” he said, tapping the spreadsheet projected on the screen behind him, “without corresponding expenses or proper deposits. The treasurer’s reconciliation does not match bank statements.” He let that sentence sit like a stone in a glass bowl. “Additionally, a vendor named Whitmore Pool Services has been paid forty thousand dollars for pool maintenance.” He paused the exact amount of time it takes for the room to remember that Maple Ridge Estates…has no pool.

A hiss traveled through the chairs. “That’s her nephew!” someone shouted. Another voice: “I saw her loading HOA plants into her SUV!”

Margaret banged the gavel so hard the handle snapped off. The head rolled to the edge of the table and fell like punctuation. “Order!” she shouted, the irony applauding itself.

“Let’s listen to a small recording,” Hawk said, his tone reasonable as a thermostat. It was my phone, my video of Margaret’s meltdown in front of my porch. Hers was a voice trained to sound like authority, stripped bare. She said single men can’t be trusted. She said she’d “run out” the undesirable elements. She said she tracked my flights through a friend at the airline. She swore she did everything for the good of the neighborhood and for control. The tape does something to words like control when you hear them one after another. It makes them into their truest shape: fear with a badge.

The board went white around the knuckles. One member stood up, touched the broken gavel head like a worry stone, and said, “Motion to remove the president per Section 12.4 of bylaws—emergency removal for criminal conduct.”

“Second,” said the treasurer, voice shaking.

“Point of order,” Margaret said. “This is illegal.”

“Point of law,” Hawk replied. “It’s not.”

The vote was not close. Fifty-eight hands for removal. Two against. Margaret’s and a friend named Eleanor who had the look of someone committed to sinking with the ship because she had stapled herself to the captain’s chair.

Margaret stood and tried to conjure dignity. “I resign,” she said.

“You’re removed,” said the board member, crisp.

The district attorney moved faster than anyone expected. Officer Bradley’s report contained more than the noise complaint. His body cam had captured the moment Margaret admitted to monitoring my travel. A search warrant flowed from a judge’s pen into a forensics team’s gloved hands. They pulled the ledger files, the HOA emails, the bank statements, the contracts with Whitmore Pool Services (registered to a P.O. box and a nephew whose LinkedIn listed “entrepreneur” and “investment in community water features”). They found more than sloppy bookkeeping. They found a map.

Eighteen counts of filing false reports. Fraud. Harassment. Violations of state HOA governance statutes. The civil suit we filed—fourteen families, four hundred thousand dollars in damages, triple damages where applicable—ran in parallel. The state AG’s office showed up because the words “pattern of discrimination” tend to magnetize their attention. Margaret talked about “burden of leadership” to anyone who still answered her calls. The rest of us wrote checks to Hawk, who told us to keep talking to each other like neighbors instead of like witnesses.

Then the forensic team pulled the journal.

I will never forget the way Hawk said the word “journal” in the conference room when he told us. He did it the way a doctor might say “tumor” if he wanted you to understand that yes, it is what it is, and also that we are going to remove it.

Margaret had kept a digital journal. She thought she deleted it. She did not. The file sat in a corner of a cloud drive, intact enough for reconstruction. It was a manifesto of petty malice. She wrote about “running out” the “undesirables.” She wrote that single men were perverts, single women were loose, renters were “trailer trash with temporary money.” She rated each false complaint on a scale of “effectiveness.” The night she leaned a speaker against my window while I flew over Kansas? Four stars. NOTE: should have made it drugs instead, harder to disprove.

When the DA read it to us, even the part of my brain that had prepared for every ugly thing could not keep up.

In court, Margaret’s attorney tried to build a cushion of words between her and responsibility—obsessive tendencies, control issues, post-employment grief. The prosecutor, a woman whose sharp navy suit matched the sharpness of her mind, held up emails where Margaret bragged to her sister: I’m keeping the standards we deserve, and making a tidy little profit. She held up contracts with the nephew’s pool company. She held up the bank records that showed a thirty percent skim on fines into an account with a name so silly it deserved charges on its own: Compliant Community Consulting. Over sixty thousand dollars routed there over two years. Vacations. Jewelry. A mortgage payment for the house whose standards she defended in newsletters like sermons.

The judge listened. He read. He asked questions twice when answers trembled into nonsense. He took a day to write a sentencing that sounded like a lesson.

“Three years in prison,” he said. “Eighteen months to serve. Five years probation. Restitution in full.”

The clerk read the list of restitution: thirty-six thousand in fines to be returned; two hundred twenty thousand in civil damages; forty-three thousand embezzled HOA dollars. A lifetime restraining order from serving on any HOA board in the state. Five hundred hours of community service, specifically with single-parent households, a line the judge read without flinching. The state real estate board revoked her license. (She’d kept it current as a badge. It became her undoing.)

When he finished, the courtroom went quiet the way a room goes quiet when a truth has settled.

Margaret stood frozen like someone paused the video. Ten seconds. Maybe twelve. Then she broke into sobs. “I was trying to keep the neighborhood safe,” she said, as the bailiff handcuffed the embossment of her name in gold.

I do not take joy in people’s destruction. I take relief in that moment when a hand reaches for your throat and then is removed.

Maple Ridge Estates learned how to exhale.

Part 3

The board appointed an interim president who’d moved to Maple Ridge because the elementary school is good, not because she craved the rush of writing warnings about trash can placement. Her name was Priya Singh, pediatric nurse, mother of two, lover of perennials and cheap wine. Her first act was to set an agenda. Her second was to set a tone.

“We are neighbors,” she said at her first meeting, voice more tired than triumphant. “Not hall monitors.”

The bylaw review committee was a parade of highlighted nonsense. Out went the odd-number flower requirement, the “dress code for mail retrieval,” and the “daytime vehicle absence aspiration,” which was not a rule but had been treated like one. We wrote accessibility into the landscaping language after Robert and Susan wheeled their ramp across the sidewalk and we all held our breath. Priya assigned me and Marcus to the “sane security” working group. We walked the neighborhood at different hours and counted lights and shadows and listened to the way sound travels between the retention pond and the cul-de-sac. We found three burnt-out streetlamps and one busted latch on the pool-that-doesn’t-exist’s gate. We fixed them. Crime is less likely when you replace a lightbulb than when you hire a tyrant.

We hosted a chalk day for the kids and adults who never got to draw large without permission. The Johnsons’ daughter drew a dragon that snaked across three driveways, tongue forked and friendly. Jennifer Santos sketched curtains that matched Margaret’s, pinned on every frame like a joke that outlived its author. Marcus taught a kid how to change a tire in the shade of a maple. Someone brought lemonade that actually tasted like lemons. I set a Bluetooth speaker on the lawn and asked who had a song. A ten-year-old picked a ballad that made a teenager roll his eyes, and we let it be and no one wrote a citation.

David Park came home from deployment. The block put flags up not because we were performing patriotism but because he is our neighbor. His driveway was full and loud for a night and no one took notes. The next morning, his toddler ran through a sprinkler wearing a diaper and an orange cape and the air smelled like everything ordinary and beautiful.

I did something uncharacteristic: I knocked on doors without a problem to solve. I brought muffins from a bakery that overpours sugar. I said hi like a person who intends to keep showing up. You can’t code a neighborhood into safety. You can only practice it.

Officer Bradley stopped by one afternoon to drop off paperwork I didn’t need but accepted because gratitude is a currency that spends easily. He brought a toy police badge for the Johnsons’ seven-year-old and did the thing where he made a siren noise under his breath that embarrassed him and endeared him simultaneously.

“Busy few months,” he said, looking toward the community center where volunteers were painting the rec room a color that wasn’t beige.

“Fewer false alarms,” I said.

“Fewer real ones, too,” he said. “There’s a correlation.”

The civil settlement checks arrived—smaller than we imagined when we were angry, larger than we expected when we were realistic. I used mine the way a person uses a raise: a little to savings, a little to fix a sagging section of fence, a little to take a weekend away to a cabin whose only rules were about not feeding bears. I did not buy a portable speaker, but I bought a doorbell with a wider angle and set a notification that says, gently, you do not have to check this tonight.

The HOA garage—Margaret’s headquarters—reverted to a garage. Priya held “office hours” in the park with a picnic blanket and a legal pad. People stopped calling board members after 10 p.m. unless something was on fire in a literal sense. The email list shifted from reprimands to requests: anyone know a good plumber, anyone have a ladder, anyone want free hostas?

Eleanor, the friend who voted with Margaret, joined the knitting circle and did not speak about it. Maybe shame taught her, or maybe she had been lonely. Sometimes the answer to power hunger is a chair in a circle.

A month after sentencing, the local paper printed a small story. They didn’t mention Maple Ridge by name, but anyone within two miles knew. The comment section was a fight I refused to read. Instead, I opened my laptop and made a document titled LESSONS FOR FUTURE ME. It contained exactly four lines:

-

Document everything.

Talk to your neighbors like people, not problems.

If someone shows you control disguised as care, believe what it is.

Make playlists that aren’t evidence.

The police report became a PDF in a folder on my cloud drive labeled RESOLVED. I didn’t print it. I didn’t frame it. But when I’m overwhelmed, I sometimes open it and scroll to the line where the officer wrote: “Mr. Pierce not home; complainant initiated disturbance.” That sentence tastes like clean water.

Part 4

I would like to tell you the story ends with a ribbon cutting—a new playground, a plaque that says resilience in a font you only use when you’re trying too hard. Life is less cinematic. It was a long, ordinary season of a hundred small kindnesses, and the shadow of what had been shrank like something that cannot withstand light.

There were hiccups. An investor bought the house on Maple and tried short-term rentals. The HOA had language for it now—actual language, not vibes—and enforced it without a gavel. A dog-walker let a bag sit on a lawn and got a note from a neighbor that said, kindly, “Hey, I think your beagle left a souvenir.” The beagle’s owner walked back with a smile and a bag.

One afternoon in spring, a county van stopped in front of the Phillipses’ house. A man in a polo and a clipboard stepped out. I felt a thud in my chest from three doors down—the old reflex. I texted Priya, who texted me back immediately: wheelchair ramp grant inspection, and I exhaled because that is what transparency feels like.

On a Tuesday in June, I saw Marcus working under the hood of his car at two in the afternoon, grease on his hands, sun on his neck. A newer resident slowed his Prius and frowned toward the driveway as if the mere presence of a hood up violated the “spirit” of something.

“You need help finding your mail?” Marcus asked, friendly but steel underneath.

“Ah,” the man said, startled. “No, just—are cars allowed to…” He trailed off as if the rules might appear on the air.

“They are,” I said, popping up from behind the mailbox like a less stylish gopher. “Rule of thumb around here: If it doesn’t hurt anyone or their access to home or work, and it’s not against written rules, we wave.”

The man nodded too quickly. It will take time for the people who learned compliance the hard way to trust that kindness isn’t a trap.

If this were the sort of story that grows a romance, now is where I would tell you Officer Bradley asked me to coffee and we laughed over ridiculous HOA war stories and discovered we both like movies where people run in the rain. That did not happen. He did bring donuts to the chalk day, though, and he smiled at a girl who asked if his badge was heavy and said, “Sometimes,” and that answer meant something bigger than he intended.

I did fall in love—with my house again. Not the paint or the mortgage or the way the afternoon light finds the east wall. With the idea that being here is not a defensive posture. It’s a choice.

People sent me links to similar stories from other neighborhoods—HOAs gone feral, petty tyrants undone by their own paper trails. There’s a legion of Margarets out there. If you are living under one, I offer you this without presumption: save your emails, set a camera, know your bylaws, talk to your neighbors, and if you can, laugh sometimes so your soul doesn’t calcify.

Margaret wrote me one letter from prison. It surprised me when I saw the return address. It surprised me more when I opened it and the first line said, “I’m sorry.” The second line undid the first: “I was only trying to keep standards.” The third line was a request: would I write a letter to support her early release because the community needed her?

I did not respond. She had earned the silence. I put the letter in the RESOLVED folder, then made a new folder called NOT MY WORK.

Robert Phillips passed away that winter. We lined the street with luminarias, and Susan said the light made the dark look survivable. Marcus carried her ramp to the curb for pick-up when she decided she didn’t want to see it every day, but he kept the screws in a labeled bag for a future neighbor who might need them.

At the next annual meeting, a man stood and asked if there was any plan to restore “the prestige” of Maple Ridge. Priya said yes, it was called not being a jerk, and the room laughed in a way that didn’t hurt anyone.

Part 5

If you want a coda, here’s one.

Two years later, the county reached out to me and to Priya and asked if we would help draft a model code of ethics for HOAs in the region. We sat in a meeting room that smelled like old paper and coffee and wrote sentences that sound obvious until you’re the one they save. Things like: Board members shall not weaponize rules; shall document complaints; shall not surveil residents; shall not profit; shall disclose conflicts of interest. We added a clause about accessibility that made Susan cry when we read it to her. We wrote a paragraph about “control disguised as care” and the room nodded because you would be amazed how many people recognize that costume.

The county adopted it. Not every HOA used it. The ones who did had fewer gavel heads breaking off and fewer neighbors measuring fences with lasers. It’s not a revolution. It is a better thermostat.

I got an alumni award from the conference people for “community resilience through digital forensics,” which is a phrase so grand it made me snort-laugh in my car. I accepted it on a stage with lights too bright, and I said the truest version I could: “I pointed a camera at a problem. The people fixed it. Also, night vision is your friend.”

On the anniversary of the citation-thick-with-duct-tape, I taped a note to my own door. I wrote it to my three-in-the-morning self—the one who would believe me. It said: You were not crazy. You were right. Also, go to sleep.

Sometimes, late, when I hear a train a mile away, my heart still speeds up. Someone knocks too loud and a muscle memory clenches. I am allowed that. Then I remember the chalk dragon and the dragon-drawing child, the beagle and the bag, the car hood up under a hot sun, the way a neighbor learned not to flinch.

The kids call me “tech Mr. Elliot” when I visit the school to teach a day on passwords and kindness, and I tell them those two things are the same idea. You protect what matters. You let the right people in.

When I mow my lawn now, Margaret does not measure the grass with a laser. She is not here. Sometimes I think of her in a fluorescent-lit room somewhere, folding prison laundry or staring at a blank wall, and I feel something that isn’t compassion and isn’t glee. It is clarity: choices and consequences have to be neighbors, too.

On a warm night in August, I set a folding chair in my driveway and watched the neighborhood breathe. The Johnsons’ dragon was a ghost now—chalk: bright, then gone, then back again. The Andersons waved. David turned a wrench and looked like contentment. Jennifer’s curtains glowed the same warm yellow as my own. Susan’s porch light made a small, stubborn circle of safety. Marcus’s car glittered under thin streetlamp light at two in the afternoon the next day and no one cared. Priya walked her kids to the mailbox in pajamas and laughed when one of them tripped and then laughed again when he stood up unhurt.

I put a slice of pumpkin bread on a plate and carried it across the street to a new neighbor, a grad student who moved in with a stack of books and a bicycle that had seen better chains. “I’m Elliot,” I said. “Welcome to Maple Ridge.”

He looked toward the community center where a sign read COMMUNITY MEETING: TREE PLANTING SATURDAY, and said, “I heard this place used to be intense.”

“It was,” I said. “It got better.”

“How?”

“Enough people wanted it to.”

He nodded. “That’ll do.”

We stood in the mild dark and listened to the world make its small noises that didn’t require enforcement. Three houses down, a portable speaker played low—not heavy metal, not evidence, just a song that made a teenager fling her arms wide in a dance no adult should judge. We didn’t. We waved.

Part 6

The last time I thought about the red letters on the duct-taped notice, it wasn’t because I was angry. It was because Noah—yes, that same Little League-batting-average grandmother flight day – turned up on my doorstep with a pie at Thanksgiving. The same boy who had to have courage stitched into his coat while he slipped his arms through sleeves in a room full of adults who didn’t deserve him? He is taller than me now. He’s visiting his mom across town and he texted first and used a period like a person who knows boundaries.

“Thought you might want dessert,” he said, grinning.

“Always,” I said.

We cut slices and ate standing up in the kitchen because plates felt like a ceremony we didn’t need. He told me about school and a project building a miniature bridge from toothpicks and glue. “Triangles,” he said, repeating a truth I now keep in a separate folder in my head. “They hold more.”

“Turns out,” I said, “the neighborhood is a triangle.”

“How?” he said, smiling because he knows what I do when I try to make metaphors work.

“Rules. People. Proof,” I said. “Any two without the third fall down.”

He shook his head the way ten-year-olds-who-are-now-sixteen do when adults think they’ve landed something. “It’s just people,” he said. “Who decide to be good.”

He is right.

When he left, the house tasted like cinnamon and quiet. I rinsed two plates that weren’t necessary and stacked them anyway. The porch light hummed. A raccoon trundled through the beech leaves with all the ceremony of a man late for a bus. A meaningless song drifted from a block over, no citation required. My doorbell blinked to let me know it was awake if I wanted it, and not offended if I didn’t.

The duct tape glue marks on my door finally faded that summer. It took time and sun and my thumb rubbing them away every time I saw them. That’s a lesson too. Some marks need chemicals. Some need weather. Some need a person deciding not to live with residue.

If you walked by my house tonight, you’d see a front window with no speaker leaning against it, a plant I will never arrange in odd numbers because I refuse to do math to please ghosts, a doormat that says HELLO in lowercase because the world has enough uppercase. You’d see a neighborhood that does not perform itself. You’d see, if you looked carefully, that the air is cleaner than it used to be. That’s what happens when you stop mistaking control for care. The particles settle. You can breathe.

At 3:17 a.m., sometimes I wake without knowing why, an old clock chiming in a part of me I don’t visit in daylight. I listen. The house is quiet. The neighborhood is quiet. I might hear an owl. I might hear nothing. I do not hear a speaker. I do not hear a text that thinks it can command me. I lie there and count triangles until I fall asleep.

If you want the ending in one sentence, it’s this: She tried to fine me for noise I didn’t make; we proved the racket was hers; we turned down the volume on her power, and turned up the people instead.

That’s the whole story. And if you ever find a duct-taped notice screaming at you from your door, I hope you have a camera with night vision, a folder called RESOLVED, a neighbor who will bring over pie, and a future self who will laugh a little, even then, because you know how the story ends.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.