Master Bought a Disfigured Slave Woman No One Wanted… Until She Called Him by His Childhood Name | HO

Seventeen miles north of Mobile, where the cypress swamps begin to breathe mist over the dark waters, stood Bogard Hall, a grand plantation built in 1798. The columns were cracked and pale as bone; the salt air from the Gulf had worn them smooth. By 1841, the estate was old money turned restless—haunted by debts, fading grandeur, and the silence that settles over houses holding too many secrets.

That February, a slave auction was held in the town square. The crowd came to buy field hands and domestic servants. Thirteen people stood in line. The twelfth—a woman with a burned face and clouded eye—was the one no one wanted.

The auctioneer hesitated when he reached her, his usual rhythm faltering. Her scars pulled her mouth into a grimace. One arm hung stiff, useless. He spoke quickly—obedient, able to work despite injuries, “healthy apart from her disfigurement.” The crowd stayed silent.

Then a voice from the back: “I’ll take her.”

The voice belonged to Thomas Bogard, 43 years old, heir to the estate, and drowning in his father’s debts. He hadn’t come to buy anyone—only to negotiate with bankers. But when the auctioneer named a figure barely above insult, Bogard nodded.

Within an hour, the papers were signed. The woman, known only as Adeline, climbed into the back of his carriage. Neither spoke for the entire journey north.

A House and Its Ghosts

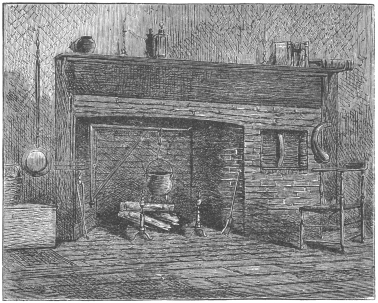

Bogard Hall loomed over the swamp road, its once-white columns graying beneath moss and mildew. The gardens had gone wild. Inside, the household ran like machinery—strict schedules, polished surfaces, measured silences.

Adeline was assigned to the laundry, where her scars would stay hidden from visitors. She worked in near silence, answering questions with brief, rasping words. She slept in a pantry off the kitchen, on a straw mattress.

No one asked about her past. She never offered it.

Three weeks later, one night when the usual servant had gone to bed, Adeline brought coffee to the master’s study. Bogard barely looked up—until her good eye met his. Something flickered there. Recognition, maybe.

That night, Thomas Bogard couldn’t concentrate. He stared at the ledgers before him—his father’s debts, the endless columns of ink—and saw only that one clouded face.

The next morning, he ordered that Adeline be reassigned from laundry to household work. No explanation.

The Song in the Library

Spring came to Alabama with heavy, honeyed air. One April afternoon, Thomas was walking past the library when he heard something faint—a low, melodic humming. A lullaby.

He stopped in the doorway. Adeline was dusting a high shelf, her good arm reaching carefully, her voice soft and distant, like memory. When she turned and saw him, she froze.

“Where did you learn that song?” he asked.

She hesitated. Then: “In the nursery. Little Tommy.”

The words hit him like thunder. Little Tommy. No one had called him that since his mother died, more than thirty years ago.

That night, the clock in the hallway struck thirteen times though it was only midnight. The servants heard it and whispered. Doors began opening on their own. A child’s footprints appeared one morning in the wet earth, leading to the back steps and ending abruptly.

The house was stirring, they said. Something had been disturbed.

Rosewood

Two weeks later, a letter arrived from Charleston. It bore the seal of the Harper family, once wealthy planters with a shipping empire that had burned to ash years before.

After reading it, Thomas locked himself in his study. The servants heard glass shatter inside. The next morning, he called for Adeline.

She entered quietly, her face expressionless.

“Do you remember Rosewood Plantation?” he asked.

Her hand trembled, but her voice was steady. “Yes, Master Thomas.”

“And what happened there, the summer of 1823?”

She didn’t look up. “I remember everything.”

He told her what he’d found—his father’s hidden journal, describing the night of the fire. The Harper family, who had planned to free their workers and expose the illegal slave trade still operating along the Gulf, were silenced by a mob. His father was one of the men who led them.

Adeline had been there. Burned. Left for dead. Sold south under a false name.

Bogard’s father had bought her.

Redemption and Reckoning

In the following weeks, Thomas became a different man. He ordered his father’s portrait removed from the hall. He freed Adeline and gave her the guest room upstairs. He began corresponding secretly with Charleston—specifically, with Rebecca Harper, Adeline’s aunt and one of the few surviving members of her family.

On July 10, 1841, Thomas and Adeline left Alabama in a private coach. Witnesses recalled that he did not sit opposite her, as a master might, but beside her.

They traveled under new names—Mr. Bogard and Miss Harper.

When they reached Charleston two weeks later, a note awaited them: an address, a time, and nothing more.

At three o’clock the next day, they arrived at a townhouse with a black door and brass knocker shaped like a ship’s wheel. Inside waited Rebecca Harper, older now, silver-haired and sharp-eyed. When she saw Adeline, she whispered, “Is it truly you?”

The reunion was quiet, aching, and electric. What followed was a confession shared between three survivors of the same crime.

Thomas revealed that his father’s journal described everything—the mob’s hooded faces, the fire, the motive. Rosewood had not been an accident. It had been an execution.

Rebecca Harper, long dismissed as a hysteric, wept as Thomas placed the journal in her hands.

The Fire Reborn

On August 15, 1841, The Charleston Mercury published an article that shook the coastal South:

“Rosewood Revisited: New Evidence in 1823 Plantation Fire.”

It named seven prominent men—judges, planters, merchants—as conspirators in the arson. Among them: Richard Bogard, Thomas’s father.

Accompanying the article was a statement from Thomas himself, confirming his discovery and vowing to testify. The same day, a petition was filed in Mobile County naming Adeline Harper as the rightful heir to the Rosewood estate.

The case tore through Alabama’s courts for three years before vanishing behind closed doors. A private settlement was reached. The terms were never made public.

But soon after, Bogard Hall was converted into a school for freed men and women, funded jointly under the names Bogard and Harper.

And Thomas? He left the South forever.

Ashes and Aftermath

In Massachusetts, he founded a small publishing house that printed abolitionist writings. Quietly, consistently, he funded schools for emancipated children. His obituary decades later described him only as “a publisher of reform literature and a friend to liberty.”

There was no mention of Alabama.

Adeline’s path was harder to trace. In 1852, records in Philadelphia list an A.H. Harper, physician, specializing in burns. During the Civil War, a Union surgeon wrote to his wife from Gettysburg:

“Among the physicians is a remarkable woman doctor from Philadelphia, her face terribly scarred. She tends both Union and Confederate soldiers alike, saying only, ‘Pain recognizes no uniform, and neither should healing.’”

Her last recorded appearance is in an 1871 physician’s registry. After that—silence.

But in a church log from Mobile, an anonymous entry appears a few years later: “An elderly woman with burns upon her face tending the freedmen of the county.”

The Lost Grave

When historian Elizabeth Carrington rediscovered the Bogard papers in 1967, she also found something else—photographs of a weathered grave behind the ruins of Bogard Hall. The inscription read:

“A.H. & T.B. – They chose truth over comfort, justice over safety. May their courage be remembered.”

No date. No records of burial. Only those initials—Adeline Harper and Thomas Bogard.

Carrington’s notes suggest they may have reunited later in life. The evidence is circumstantial, the conclusion uncertain. But the grave exists.

Buried Stories, Unquiet Truths

For more than a century, the story of Rosewood and Bogard Hall remained buried—suppressed by powerful families, erased from court records, quietly forgotten by official historians. Fires, floods, and “lost” archives all seemed to conspire in silence.

Yet the fragments that survived tell a story impossible to ignore: a man who discovered his father’s sins, and a woman who faced the man whose name once commanded her pain.

She could have hated him. Instead, she demanded justice—and he chose to help her get it.

Their story was never one of romance. It was one of recognition—of a moment when two people saw each other clearly across an unbridgeable divide and refused to turn away.

Echoes in the Swamp

Today, nothing remains of Bogard Hall but its foundations and the family cemetery overgrown with ivy. Locals say that on stormy nights, when thunder rolls across the Alabama sky, you can hear a woman singing near the ruins—a soft, wordless lullaby.

Some swear the song ends with a name spoken tenderly into the rain: “Little Tommy.”

And if you listen closely—so they say—you might just hear a man’s voice answering from somewhere in the trees.