THE MOMENT I BECAME A STRANGER TO YOU

Mom, I don’t know if you can read this wherever you are, or if there’s even an “wherever” anymore. But I need to tell you something I’ve been carrying for thirty years like a stone in my chest that never gets lighter—only heavier with time.

I was fifteen years old when I said something to you that I would spend the next three decades trying to undo.

It was April 1995. Spring in California. You had called the house looking for Uncle Joe, and I answered the phone. I remember that moment with a clarity that has never faded—the weight of the receiver in my hand, the sound of your voice traveling through the telephone lines, that familiar register I knew as “Mom” even though you hadn’t been “Mom” in any real sense for years.

But hearing your voice wasn’t what made me angry. It was everything that voice represented.

The Weight of Abandonment

All the years of you not being there. All the birthdays you missed. All the times I waited by the window on Saturday afternoons, certain you would come to pick me up, only to watch the light fade while Uncle Joe made me dinner because you weren’t coming. All the nights I cried into a pillow because I didn’t understand why my mother—my actual mother—had chosen a needle over me. That’s what your voice brought back: the child in me who was still waiting by that window, still wondering why I wasn’t enough to save you.

I had built a story about you over those years. A story where you were the villain, the fallen woman, the addict who didn’t care. It was easier than the real story—which was that I was a kid who hurt, and I needed someone to blame.

So when I heard your voice that April day, something broke open inside me.

“Why didn’t you just have an abortion?” I screamed into the phone.

I remember the venom in those words. I remember how deliberately cruel I was making them, shaping them like weapons in my mouth before releasing them through the receiver to find you on the other end.

“You obviously never loved me.”

There. That was the killing blow, the thing I said last before giving you a chance to respond. I didn’t ask you about your life. I didn’t ask how you were doing. I didn’t even let you explain why you’d called. I just unloaded fifteen years of pain and anger onto a woman who was probably already suffering far more than I could have imagined.

Mom, I was a child. I know that now. Children are cruel because they don’t have the framework yet to understand complexity. They see things in black and white—loved and abandoned, safe and betrayed, worthy and worthless. And I had decided, at fifteen, that you fell into the worthless category.

But what I didn’t know—what I couldn’t have known—was that I was on the phone with you for the last time.

The Words That Changed Everything

And then you said something that unmoored me.

Your voice was soft. So impossibly soft. Like you were speaking to me across a distance much greater than the telephone lines separating us—across a distance of years, of loss, of all the ways I had rejected you.

“I do love you,” you said. “Not everything you’ve been told about me is true.”

I remember my breath catching. I remember the world going very still.

You told me you had tried to visit me. When I was a toddler, after I was found alone in your apartment and placed with Uncle Joe, you said you had tried to see me. You said no one would let you in the door. You said you wanted to be in my life but the family—our family—had made it impossible.

But I was fifteen, and I had been lied to before. I had been disappointed before. I had been abandoned before. And my heart, which was already so defended, so armored against the possibility of loving you again, rejected what you were saying as another manipulation, another lie, another broken promise.

So I called you a liar.

And I hung up the phone.

I don’t remember what I did after that. I don’t remember if I felt relief or guilt or anger. The human mind is kind that way—it protects us by blurring the details of moments too painful to hold clearly. But I know I didn’t think about you much after that day. I had so many other things to be a teenager about. Homework. Friends. Crushes. The normal concerns of a fifteen-year-old girl who had convinced herself she didn’t need her mother.

The Disappearance

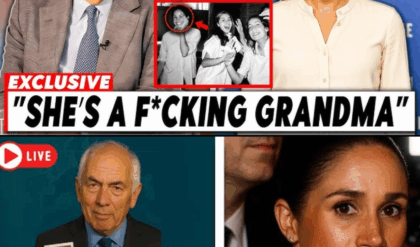

Six months later, on October 12, 1995, you walked out of a motel room to buy a pack of cigarettes.

You never came back.

The man you were living with didn’t report you missing right away. It took him days. When he finally did, the police took a report, asked a few questions, and made a few notes. Detective Tom Bowler, who was assigned to your case, concluded fairly quickly that you had probably been murdered. But “probably” wasn’t good enough. There was no body. No physical evidence. Just the story of a woman who was well-known to the local police—a drug addict, a sex worker, someone the system had already written off.

So your case went cold before it ever really got warm.

I was fifteen. I was living with Uncle Joe, living the life that had become normal to me—the life where I had a guardian but no mother. When he told me you were missing, probably dead, my reaction was strange. I cried. I remember that. But underneath the tears was something else. Underneath was anger, and underneath the anger was relief.

Relief that I didn’t have to think about you anymore. Relief that the question of whether I could forgive you, whether I could rebuild a relationship with you, whether I could ever trust you again—that question was gone. You were gone. And I could be angry with you forever without the complication of you actually being alive, actually being able to explain yourself, actually being able to contradict the story I had built about you.

Our family didn’t search for you. We didn’t make flyers. We didn’t call the news stations or organize search parties or beg the community for information. We accepted the police’s version of events—that you had probably been murdered, that this was the natural consequence of the life you lived—and we moved on.

There was no memorial service. No gathering of family members to grieve together. No formal goodbye. We simply erased you.

And I, especially, erased you.

Three and a Half Years of Silence

For three and a half years, I didn’t think about you. Or rather, I tried not to. I tried to live the life of a girl whose mother had never existed in the first place.

I was eighteen when the dream came.

I was in college by then, building a new identity, becoming a woman who was separate from the story of her abandonment. The dream was simple, but it shattered everything I had built.

You were standing in front of me—not as I remembered you from childhood, but clear, translucent, your blue eyes (the eyes I inherited) locked onto mine. You didn’t speak. You didn’t need to. But I understood you perfectly. You were showing me something. A man. Tall. Brown hair. Brown eyes. And then the dream released me back into consciousness, and I woke gasping.

I didn’t understand that dream. I didn’t know what you were trying to tell me. But I knew, in the way you know things in dreams, that it meant something. That it meant you were trying to reach me. That it meant, somehow, you hadn’t been entirely erased after all.

The Question I Couldn’t Ignore

And then I started asking myself the questions I had been avoiding for three and a half years.

What if I had been wrong about you? What if some of what you told me on that phone call in April was true? What if you had really tried to visit me, and my family had really kept you away? What if the story I had built about you—the story where you were simply a bad mother who chose drugs over her children—was only half the truth?

What if you had been a person? A complicated, flawed, struggling person, but a person nonetheless?

These were dangerous questions. They threatened to undo the armor I had built around my heart. They suggested that my anger, which had been so useful for so long, had been misdirected. That instead of being angry at you for abandoning me, maybe I should have been curious about you. Maybe I should have asked questions instead of making accusations. Maybe I should have listened instead of hanging up.

But curiosity is a door once opened, and I couldn’t close it.

So I called the West Sacramento Police Department.

I told them I was Tami Seymour’s daughter, and I wanted to know what had happened to my mother. I wanted to know if there were any new leads, any new evidence, anything that could explain why a woman had walked out of a motel room on October 12, 1995, to buy a pack of cigarettes and never come home.

The detective they connected me with was named Jim Duncan. He was unfamiliar with your case, but he said something that sparked a small hope in me: he was equally curious.

The Beginning of Understanding

Within six months, Jim had identified a suspect. Someone who had been in contact with you around the time of your disappearance. He had circumstantial evidence—failed voice stress tests, a changing story about seeing you alive years after you vanished, a witness who admitted to being coerced into lying. It wasn’t enough for charges, but it was something. It was evidence that your death mattered. That your case was worth investigating.

“Without a body,” Jim said to me, “it’s unlikely we’ll ever solve this. I’m sorry.”

But I wasn’t sorry. For the first time since that phone call in April 1995, I felt something other than anger or grief or guilt. I felt something like purpose.

I was going to find out what happened to you, Mom. Not because our relationship had been good—it hadn’t. But because you deserved more than to be forgotten. You deserved more than to have your death accepted as the natural consequence of your life. You deserved for someone to care. And since no one else seemed to care, I was going to care enough for all of us.

I was going to spend the next thirty years looking for answers.

I was going to spend the next thirty years trying to take back those last words I said to you.

I was going to spend the next thirty years learning who you actually were, beneath all the stories, beneath all the pain, beneath all my anger and your addiction and the family’s shame.

And I didn’t know it yet, but in doing so, I was going to learn something far more important than what happened the night you disappeared.

I was going to learn who I was.

SEARCHING IN THE DARK

For the next decade, I thought of you often—but I also believed there wasn’t anything more I could do.

After Jim’s words—”Without a body, it’s unlikely we’ll ever solve this”—I fell into a kind of waiting. A waiting that looked like acceptance. Every time I heard news of an unidentified body found in California, I would feel a strange flutter in my chest. A terrible, shameful part of me hoped it would be you. Because at least then we would know. At least then there would be an ending.

And when it wasn’t you, I would feel that sting again—the sting of not knowing. The sting of you being out there somewhere, in the vast machinery of missing persons files and cold cases, waiting for someone to remember you. Waiting for someone to care.

That was me. I was the one remembering. I was the one who cared.

Finding NamUs

In 2009, fourteen years after you disappeared, I learned about a website called NamUs.gov.

The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. It sounds so official when you say it out loud. So important. The website had launched in 2006 to help law enforcement and victims’ families compare missing persons cases against unidentified remains. For the first time, families didn’t have to rely entirely on local police departments with limited resources. For the first time, there was a database where you could search nationwide. Where you could match your missing loved one against Jane Does and John Does found in any state in America.

I realized you weren’t listed.

I created your profile myself, Mom. I sat at my computer, pulling up those childhood memories—your blue eyes, your dishwater blonde hair, the tattoos you had gotten during years on the streets. I looked at the missing persons poster on the California Attorney General’s website, and I tried to describe you as accurately as I could for the algorithm.

It felt like I was making you real again. Like I was saying to the entire system, “This woman existed. This woman mattered. This woman is still missing, and someone should be looking for her.”

Registering you on NamUs.gov gave me permission to push harder.

I began searching the database monthly. Sometimes weekly. I would read through descriptions of unidentified remains found across California—women of approximately your age, your build, your hair color. Women found in ditches, in forests, in abandoned buildings. Women without names, without families, without anyone to claim them. I would examine their information obsessively, looking for any detail that might match you.

Height? Maybe. The decomposition makes measurements unreliable.

Hair color? Possibly. Blonde can fade or darken depending on conditions.

Time of death? If they estimated between 1995 and 2000, it could fit.

I would fill out contact forms. I would call the West Sacramento Police Department. Again. And again. And again.

Most of the time, no one called back. But occasionally—occasionally—a detective or lieutenant would reach out. They would promise to look into your case. They would sound sympathetic. And then they would disappear back into the thousands of other cases stacked on their desks, their computers, their minds.

I learned, slowly, that it wasn’t personal. Resources are limited. New cases take precedence over old ones. Solvability is the metric that matters. A murdered woman from thirty years ago, a woman with no body, a woman the system had already written off—she doesn’t rank high on the priority list.

Martha

But then, in 2015, something unexpected happened.

A retired detective from the West Sacramento Police Department named Martha Barbosa called me.

She had heard about your case through her former colleagues. She wanted to know if I would allow her to look into it in her free time, as a way to help the department. As a way to help me.

Mom, I cannot tell you what that phone call felt like. After years of unreturned messages, dead-end searches, the system slowly closing its eyes on you—suddenly there was this woman, this retired detective, offering to care. Offering to remember.

I agreed immediately.

Martha was warm. She had a voice that made you feel safe. Over our phone calls, I would tell her things I hadn’t told anyone. I told her that you and I weren’t close. That you had abandoned me as a baby for drugs. That I had only visited you on weekends for a few years before our relationship ended, long before you actually vanished.

And Martha would listen. She would let me tell the painful parts of your story without judgment. And then, in the gentlest way, she would say things that cracked open my heart.

“I’m sure your mother loved you in her own way,” she said during one of our conversations.

I had spent thirty years—well, thirty years by then—telling myself that you didn’t love me. That you had chosen drugs over me. That your love, if it ever existed at all, was less powerful than your addiction. But Martha said it so simply, so gently, that I couldn’t argue with her.

Maybe you did love me, in your own way.

The Purse

On the eve of my thirty-sixth birthday, Martha called with news.

“We found your mom’s purse,” she said.

I was standing outside my house in Southern California. It was midday. The sun was hot on my face. And for a moment, I couldn’t think. Couldn’t breathe. Your purse. All these years, and no one had looked through your purse.

“Where was it?” I managed to ask.

“In the evidence locker,” Martha said. “There’s no log showing when it was found or by who. But I think it may have been there all along and someone forgot to process it. It was never even opened.”

I pictured it, Mom. Your purse, sitting in a locker for twenty years. Untouched. Unexamined. Like they had filed you away and forgotten to look.

Martha and the department’s forensics detective, Ruth Pagano, opened it. They documented everything. And then Martha called me back with something that made me cry harder than I had cried in years.

“In her wallet was a baby picture of you,” Martha said. “Wearing a red dress, sitting on your brother’s lap.”

I knew that picture. It had hung in my grandmother’s hallway for sixteen years. It was a picture that suggested we were a normal family. That we were happy. That we were loved.

“She wrote ‘My babies 1981’ on the back,” Martha continued. “She loved you. She kept you with her.”

Mom, I was standing in the sun outside my house, and I was crying so hard I could barely stand. Martha could hear the tears through the phone. And she let me cry. She didn’t try to fix it or make it better. She just let me grieve for a moment.

She let me grieve for you.

The Contents of Your Life

A year later, the West Sacramento Police Department mailed me your purse as a gesture of kindness.

The current investigator, Detective Andrea Barnett, had to document every single object inside it—more than two hundred detailed photographs—before they could release it from evidence. For this, I was grateful. For this small act of respecting you as a human being and not just a case number.

When I opened that purse, Mom, I held my breath.

First, I found that picture. The one of me and my brother. I held it carefully, like it might disappear if I wasn’t gentle enough. On the back, in your handwriting: “My babies 1981.”

You had kept us with you.

But there was so much more. Three pocket calendars. Address books. Your expired driver’s license. Two misdemeanor citations for prostitution. Handwritten notes in your own handwriting. And something that made me cry again—the paperwork you signed in 1984 to make Uncle Joe my legal guardian.

You were planning to give me to him. You knew you couldn’t take care of me. You knew you were disappearing into addiction, and instead of letting me disappear with you, you made the most loving decision you could make in that moment. You signed the papers that would make sure I had someone safe.

In that purse, I found more love than I had ever recognized you for.

The Woman Inside the Victim

But Mom, what I found most powerful were the clues about who you were beyond the addiction. Beyond the crimes. Beyond the abandonment.

There were three pocket calendars, and they had your handwriting all over them. Notes. Plans. Dreams.

You were looking forward to celebrating your 38th birthday. You had written it down in your calendar, like you believed you would make it to October 22, 1995. Like you believed you had a future.

There were notes about a health clinic—a detox facility. You were considering it. You were thinking about getting clean.

There were notes about a man named Johnny. You had written his name down several times, and next to it, little hearts. But Johnny didn’t love you back. The notes suggested he was in your life for a moment, and then he was gone. And you carried that small heartbreak around with you.

There was paperwork about financial stability. You were thinking about money, about building a stable life. You had plans, Mom. You had actual plans.

What I learned from your purse was that you were not simply a drug addict, or a sex worker, or a bad mother. You were a woman. A complicated, flawed, struggling woman—yes. But a woman with hopes. A woman with dreams. A woman who wanted to celebrate her birthday and get clean and maybe fall in love and have a stable life.

A woman, not a victim.

Or rather—a victim who was also a woman.

The Search Continues

After I received your purse, I continued searching NamUs.

In October 2018—twenty-three years after you disappeared—I found something that made my heart stop.

A Jane Doe. Found in 2000 in Sacramento, just three miles from where you were last seen. Caucasian. Between 21 and 53 years old. Estimated death between 1995 and 2000. The description fit.

I called Heather Griffiths, the Sacramento County deputy coroner.

“I think this might be my mother,” I said. My voice was shaking. I was trying so hard to sound calm, but my whole body was trembling.

Heather paused. And then she said something that stopped my hope dead in its tracks.

“She can’t be your mother. I’m so sorry. But this woman had some teeth in her lower jaw, and your mom’s NamUs profile says she has full dentures.”

I panicked. The truth was, I had no idea if you actually had full dentures. I had filled that information in based on a childhood memory of you pulling out fake teeth to make me laugh. I had put information into that database without being entirely sure it was accurate.

But I couldn’t ignore the possibility. So I tracked down a family friend. And she confirmed it—yes, you had a couple of bottom teeth. You weren’t completely toothless.

So Jane Doe might be you.

And that’s when my real obsession began, Mom. That’s when I truly understood what thirty years of searching would look like.

Because it wasn’t just about finding you.

It was about learning to be patient with a system that was broken. Learning to understand why resources were limited. Learning to live with uncertainty while hoping for resolution.

Learning to carry you with me every day.

THE WAITING ROOM OF HEARTBREAK

“It can take a year or more to get a body disinterred,” Heather explained to me over the phone.

A year. To dig up a body. To run a DNA test. To get an answer to a question I had been asking for nearly twenty-five years.

I told myself I understood. I pretended to be patient. But privately, I was agonizing. In my mind, it seemed so simple. Take a sample. Run it through a machine. Get an answer. But Heather was kind in her explanations. She told me about the bureaucracy. About needing money to dig up an unidentified body. About nearly three thousand new bodies processed each year by her office, with resources that never seemed quite enough.

I called her every few weeks.

Each time, she was patient with me. Each time, she explained why things were moving slowly. Each time, I tried not to cry on the phone.

The DNA Dance

Eighteen months later, in February 2020, Heather invited me to Sacramento to meet in person.

She needed three separate DNA samples from me. A prerequisite for the thing I had been dreaming about for nearly two years—the exhumation of Jane Doe. Finally, we were going to know.

I drove to Sacramento. I gave her my DNA—three samples, collected carefully, documented officially. I sat across from Heather, and for the first time, I allowed myself to imagine it. Imagining you being found. Imagining finally having an answer. Imagining being able to bring you home.

Days later, Jane Doe was exhumed. Her remains were tested against my DNA.

The results were supposed to be instant. An hour at most, Heather had told me. An hour from the time they unearthed her remains.

But the results took weeks.

Heather called me, and I could hear something in her voice. Something heavy.

“We had a problem,” she explained. “An underground water leak saturated her remains. I can’t sequence the DNA sample I collected. We’re going to have to try again. But it’s going to take more time.”

More time. I had already given thirty years. I had already waited through two decades of silence. But I said okay. What else could I do?

The Waiting

For two weeks, I felt disconnected from everything.

From my body. From my family. From the world around me. All I could think about was Jane Doe. All I could think about was you. All I could imagine was the phone call that would finally end this. The phone call that would tell me—yes, we found her. We found your mother. After all this time, we finally found her.

I imagined how I would tell the family. How we would process it. How we could finally have closure—that word that everyone uses, that I had started to believe was an impossible dream.

Then, in early March 2020, Heather called again.

“I’m so sorry,” she said. “It isn’t your mother.”

The air left my lungs. It felt like I couldn’t breathe. Like I was drowning, but slowly. Like I was being pulled underwater by something I couldn’t see or fight.

“Who is she?” I managed to ask.

“We still don’t know,” Heather said. “Her information is in CODIS. Hopefully, soon, we’ll get a match.”

CODIS. The FBI’s Combined DNA Index System. Another database. Another waiting room. Another woman waiting to be found.

And I was one of thousands of people—thousands—in the same situation. Waiting for a match. Waiting for an answer. Waiting for someone to remember them.

The World Stops

Days after that call, the world changed.

Our country went into lockdown as the pandemic took hold. COVID spread across America like a ghost, and suddenly, my search for you seemed very small. Suddenly, there were bigger problems. Bigger fears. Bigger losses.

I stopped calling the coroner’s office. I stopped searching NamUs. I stopped everything. I was worried about my family, about whether we would survive the pandemic, about whether anyone would survive.

My search for you became something I could set down, at least temporarily, in the face of a global catastrophe.

It took me ten months to find the courage to call Heather again.

Learning the System

But this time, I called her as a writer.

I was collecting stories, gathering information about how cases like yours get solved—or more often, how they don’t. I was trying to understand the system that had failed you. The system that had failed so many women like you.

“Jane Doe still hasn’t been identified,” Heather told me during that interview. “It could mean several things. She was never reported missing. She wasn’t from the Sacramento area. Or her family never submitted a DNA sample. Or it’s a combination of all three.”

“What’s next?” I asked.

“For that particular case,” she said, “now that we haven’t had a match in CODIS, the next step would be someone reports her missing and provides a DNA sample, or we do a genealogy profile.”

Genealogy. Like the kind law enforcement had started using to track down serial killers using at-home DNA testing companies. The kind that could help identify unknown remains.

But there was the same problem again: money.

Later, I spoke with Heather’s boss, Sacramento County Coroner Kimberly Gin. She was frustrated. I could hear it in her voice.

“Funding absolutely impacts what we can do for our cold cases,” she said. “With the increased number of deaths over the years and the rising number of deaths due to the pandemic, we are struggling to just maintain day-to-day operations. Coroner’s offices across the nation are notoriously underfunded and understaffed. Finding the funds to actually pay for disinterments, added genetic testing, and supplies for Rapid DNA testing has been a struggle.”

She told me something else that stayed with me. “We do have issues with families not trusting the system when it comes to giving up their DNA samples. I don’t know how to get them to trust us, other than to say that we only use family samples for the sole purpose of identification of their loved one.”

That made me sad, Mom. That families didn’t trust the system to help find their loved ones. But I understood it. I had felt that frustration. That sense that the system didn’t care. That the system had already moved on.

Your Purse Comes Home

A month after my interview with Kimberly, the West Sacramento Police Department mailed me your purse.

A gesture of kindness. A way of saying: we remember her. We know she mattered.

Detective Andrea Barnett had documented every single object inside it. More than two hundred photographs. Every item. Every note. Every corner of your life, catalogued and preserved and respected in a way you hadn’t been respected in death.

I held that purse in my hands, and I understood something. The system wasn’t entirely broken. There were people in it—Martha, Heather, Andrea, Kimberly—who cared. Who remembered. Who treated missing women like they mattered.

But there weren’t enough of them. And the resources weren’t there. And for every woman like you, there were thousands of others waiting.

What I Learned

Mom, I’ve spent thirty years searching for you.

Thirty years looking through databases. Thirty years calling police departments. Thirty years collecting your stories. Thirty years trying to understand who you were beyond the addiction, beyond the crimes, beyond the abandonment.

And what I’ve learned is this:

I learned that you were more complicated than I knew. That you were a woman trying to survive in a system that didn’t protect women like you. That you loved me, even if you couldn’t show me in the ways I needed you to. That you had dreams, and plans, and a future you believed in right up until the moment you disappeared.

I learned that the criminal justice system doesn’t care equally about all victims. That a woman who is a drug addict and a sex worker doesn’t get the same resources as a woman from a respectable family. That cold cases go cold not just because of time, but because of negligence. Because of budget cuts. Because of priorities that don’t include women like you.

I learned that your absence taught me something more important than your presence ever could have. It taught me that love isn’t only about what we receive. It’s about what we give. It’s about showing up for people even when it’s hard. Even when the system makes it difficult. Even when it would be easier to walk away.

I learned that I could forgive you, Mom. Not just for the ways you hurt me, but for the ways the world hurt you. Not just for being absent, but for fighting to survive in a world that seemed designed to break women like you.

And most importantly, I learned that I could forgive myself. For the cruel words I said when I was fifteen. For the anger I carried for so long. For the years I spent hating you instead of trying to understand you.

Still Searching

But to date, Mom, your case remains unsolved.

I still don’t know what happened the night of October 12, 1995. I still don’t know if the man in my dream—tall, brown hair, brown eyes—was your killer. I still don’t know if you suffered. I still don’t know if you fought, or if you accepted what was happening.

I still don’t know where you are.

But I’m still looking. I’m still searching. I’m still calling. I’m still believing that somewhere, someone knows something. Somewhere, someone saw something. Somewhere, someone has information that could crack open this case after all these years.

I continue to search NamUs.gov. I continue to monitor unidentified remains. I continue to hope that one day, a genealogy profile will match you to your DNA in some database. That one day, someone will report information that will help us understand what happened.

To anyone who was in West Sacramento on October 12, 1995, I’m asking you to remember. Do you remember seeing a woman with blue eyes and dishwater blonde hair? Do you remember the motel? Do you remember anything unusual that night?

To the man who was with my mother that night—the ex-boyfriend who reported her missing—I’m asking you to reconsider what you’ve carried with you all these years. Is there anything you haven’t told the police? Is there any detail, no matter how small it seems, that might help us find her?

Anyone with information about Tami Seymour’s disappearance is encouraged to call the West Sacramento Police Department at (916) 372-3375, and reference case number 958376. You can also contact the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department or the California Attorney General’s office.

The Apology I Still Owe

Mom, I know I said I’m sorry. I know I’ve been trying to take back those cruel words I said when I was fifteen.

But the truth is, I’m not sure an apology is enough. I’m not sure anything is enough.

What I can tell you is this: I see you now. I see the woman you were. I see the plans you had. I see the love you carried in your wallet in the form of a baby picture. I see the birthday you wanted to celebrate. The detox you wanted to try. The stability you wanted to build.

I see you, Mom. And I’m sorry it took thirty years for me to do so.

I’m sorry you had to die for me to understand you. I’m sorry the world was cruel to you. I’m sorry I was cruel to you. I’m sorry that even now, we don’t have the resources to properly investigate your death. I’m sorry that you matter so little to a system designed to protect women, when you so desperately needed protection.

But I will keep searching. I will keep remembering. I will keep telling your story—not as a fallen woman, not as a cautionary tale, but as a human being who deserved better. Who deserved love. Who deserved safety. Who deserved to live.

I will keep searching until I find you, Mom.

And even if I never do, I will keep you alive. In my memory. In my words. In the persistent, unshakeable belief that thirty years is not too long to wait for justice.

Not for you, Mom. Not for my mother.

Never too long.