The sound of gravel crunching under yellow metal. That’s what Janice McKinney heard through her kitchen window on that Friday afternoon. The familiar rumble of the school bus, right on schedule. The accordion doors folding open. The mechanical hiss of brakes releasing.

She didn’t rush to the window. Why would she? Her daughter made this walk every single day. Fifty feet from the bus stop to the base of their driveway. Then another hundred yards uphill to their front door. Less than two minutes, door to door.

Janice was planning something special that afternoon. A playdate. She’d promised Cherrie that morning, and her daughter had been excited all day. The kind of excitement only an eight-year-old can muster for something as simple as playing with friends.

But as the seconds ticked by, that kitchen stayed empty. The door never opened. The sound of small feet on the driveway never came.

And in those fifty seconds it should have taken Cherrie Ann Mahan to walk from that school bus to her home, an entire lifetime disappeared.

The Last Normal Morning

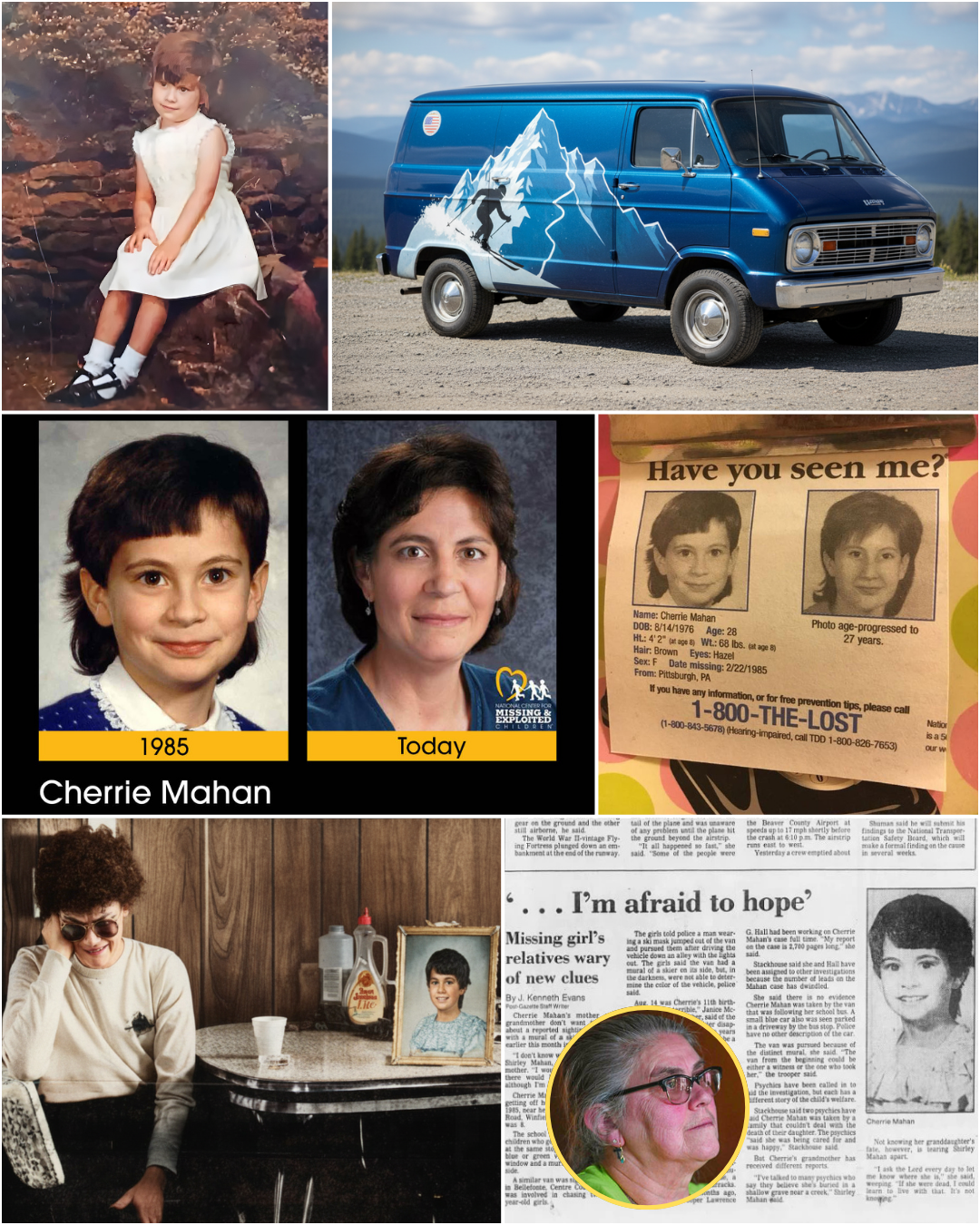

February 22, 1985, began like any ordinary winter day in Winfield Township, Butler County, Pennsylvania. The kind of cold that makes your breath hang in the air, the kind that turns dirt roads into frozen ruts. Cherrie Mahan woke up in her room, pulled on her favorite outfit—a gray coat over a blue denim skirt, blue leg warmers bunched around her ankles, beige boots on her feet—and got ready for school.

She was eight years old. Born to a teenage mother who’d been just sixteen when Cherrie came into the world, the little girl was everything to Janice McKinney. Her whole world. The center of her universe. They lived together in a modest home at the end of an uphill gravel driveway, the kind of rural Pennsylvania setting where everybody knew everybody, where kids played outside until dark, where school buses were as reliable as sunrise.

That morning, Janice walked with Cherrie down to the bus stop. It was their routine. Fifty feet from their driveway to where the big yellow bus would pull over on Cornplanter Road. Mother and daughter stood together in the cold, breath making small clouds between them. When the bus arrived, they said what they always said to each other.

“I love you.”

“I love you too.”

Cherrie climbed aboard, her backpack nearly as big as she was. The doors closed. The bus pulled away. Janice turned and walked back up the driveway to their house, already thinking about that afternoon’s playdate. Already planning what snacks to set out.

She had no idea she would never see her daughter again.

4:10 PM: The Yellow Door Opens

The school bus made its usual route that Friday afternoon. Same roads. Same stops. Same driver who’d been driving these kids for months. At approximately 4:10 p.m., the bus slowed to a stop on Cornplanter Road, right where it always did.

Cherrie stepped off with three of her friends. All four girls spilled out onto the roadside, bundled against the February cold, chattering the way children do after a long day trapped in classrooms. One of the mothers, Debbie Burk, had followed the school bus in her own car. She was there to pick up her daughter and the other girls for their own plans.

Debbie watched as the four children gathered on the side of the road. She watched as three of them walked toward her car. And she watched as Cherrie Mahan turned away from the group and began walking toward her home.

There was a vehicle parked near the bus stop. A van. Bluish-green in color, boxy and worn like so many vehicles from the 1970s. But this one had something distinctive painted on its side—a mural depicting a skier carving down a snow-covered mountain. Vivid. Unusual. The kind of detail that sticks in your mind.

Cherrie walked past that van. Debbie Burk saw her do it. The little girl in her gray coat and blue leg warmers, backpack bouncing on her shoulders, turned the corner where the driveway met the road and started up that familiar hill toward home.

And then she was out of sight. Just around the bend. Just out of view.

Debbie Burk drove away with the other children. The school bus pulled back onto the road and continued its route. The van with the skier mural was still there, idling on the shoulder.

Nobody saw what happened next.

The Silence That Screams

Minutes passed. Five. Then ten. Inside the house at the top of that driveway, Janice McKinney went from expectant to confused to worried. The bus had come. She’d heard it. The unmistakable sound of it stopping, of doors opening and closing, of it driving away. All the sounds that meant Cherrie was on her way home.

But the door stayed closed. The driveway stayed empty. The house stayed silent.

At first, Janice thought maybe Cherrie had stopped to play. Maybe she’d found something interesting on the walk up. A bird. A patch of ice. The kinds of distractions that capture a child’s attention for just a moment. But those moments stretched longer. And longer.

By the time Janice walked outside and looked down that driveway, her heart was already hammering. The cold bit into her face as she called her daughter’s name. Once. Twice. Her voice carrying across the frozen Pennsylvania hillside, bouncing off trees, dissipating into nothing.

No answer came back.

She walked down the driveway, calling. Reached the road. Looked both ways. Nothing. No small figure in a gray coat. No blue leg warmers. No backpack.

Just empty road. Empty woods. Empty air.

The panic that set in then was the kind that never really leaves. The kind that lives in your chest for the rest of your life, pressing down, making it hard to breathe. Because somewhere between that school bus door and her front door—a distance of maybe 150 yards, maybe fifty seconds of walking—Cherrie Ann Mahan had simply vanished.

The Search That Consumed A Community

Within hours, the Butler County landscape transformed into something out of a nightmare. Police cars lined Cornplanter Road, their lights painting the twilight in shades of red and blue. Bloodhounds arrived, noses pressed to the ground, trailing back and forth along that driveway, along the road, into the woods. Helicopters chopped overhead, searchlights cutting through the gathering darkness.

Every neighbor within miles mobilized. Parents who’d just picked up their own children from that same school bus. Farmers who worked the surrounding land. Shopkeepers from nearby Cabot. Within the first twenty-four hours, an estimated 250 volunteers joined the search, combing through Butler County’s frozen terrain, calling Cherrie’s name until their voices went hoarse.

They searched abandoned buildings. Barns. Sheds. Drainage ditches. The thick Pennsylvania woods that surrounded the Mahan home, where winter branches made skeleton fingers against gray sky. They walked in lines, arms linked, eyes scanning every inch of ground for any sign—a scrap of gray coat, a beige boot, anything.

Nothing.

The local community raised $39,000 as a reward for Cherrie’s safe return. A local business pledged another $10,000 for information leading to an arrest. The numbers kept climbing because everyone felt it—that sick, helpless feeling that one of their own had been taken. That it could have been their daughter. Their granddaughter. Their niece.

But money couldn’t bring back what had been stolen in those fifty seconds. All the searching in the world couldn’t change the fact that an eight-year-old girl had walked past a blue van with a skier painted on it and never made it home.

The Van That Haunted A Generation

The blue van became everything. Police received hundreds of tips about it—people who’d seen a similar vehicle, people who knew someone who owned one, people who thought maybe they’d noticed it in the area before. Every lead was pursued. Every blue van in western Pennsylvania was tracked down and examined.

They found one that seemed to match. A bright blue 1976 Dodge van, owned by a woman named Donna Patterson who lived just five miles from where Cherrie disappeared. And yes, it had a mural of a skier going down a mountain painted on the side.

For a moment, it seemed like the answer had been found.

But when police investigated, they discovered the van had been parked at a local steel corporation at the exact date and time Cherrie vanished. Donna Patterson’s brother-in-law worked there. The van had been accounted for. It wasn’t involved.

Which meant somewhere out there was another blue van with a skier mural. Another vehicle that had been parked on Cornplanter Road that February afternoon. Another driver who’d been watching when that school bus opened its doors.

Despite examining numerous similar vans over the decades, despite thousands of hours of investigation, that vehicle was never found. Pennsylvania State Trooper Jim Long would later tell CBS News, “There have been numerous vans we have examined. Unfortunately, none of them have led us to any significant findings”.

The mural of the skier became an icon of loss. It appeared on Cherrie’s missing persons poster—the very first poster ever distributed by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. That image of a vehicle, of a mountain, of a figure skiing down a slope, became seared into the consciousness of an entire generation.

To this day, that van has never been identified. And whoever was driving it that day has never been found.

A Mother’s Forty-Year Vigil

Janice McKinney did what any mother would do. She refused to stop. Refused to give up. Refused to accept that her daughter was simply gone.

In the years that followed Cherrie’s disappearance, Janice became a fixture in missing children advocacy. She kept her daughter’s case alive through sheer force of will. She gave interviews. She distributed flyers. She followed every lead, no matter how small or unlikely. When the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children asked to use Cherrie’s case as their very first featured missing child, Janice said yes without hesitation.

The poster they created showed Cherrie’s school photo—that innocent eight-year-old face, hair neatly combed, small smile, pierced ears—alongside a description of what she’d been wearing and an image of that blue van with the skier. It was mailed to homes across America. Pinned to bulletin boards in post offices and grocery stores. Tucked into millions of pieces of mail.

It sparked a movement that would change how America searched for its missing children. The “Have You Seen Me?” campaign. Photos of missing kids on postcards, on milk cartons, on billboards. Cherrie Mahan’s face became the face that launched a nationwide effort to bring lost children home.

But for Janice, it was never about movements or campaigns. It was about her daughter. Her little girl who’d said “I love you” that morning and never said it again.

The leads came in for years. Decades. Some cruel. Some hopeful. Some devastating.

In the 2010s, Janice received a handwritten letter. It was graphic. Detailed. It described how Cherrie had been killed and where her body was supposedly buried. The cruelty of it shattered something in Janice. She handed the letter to police, who followed up on every detail. They searched the locations mentioned. They investigated the claims.

Nothing was found. It had been a hoax. Someone’s sick idea of a joke.

Over the years, several women came forward claiming to be Cherrie. Each time, Janice’s heart would seize—hope and terror mixing into something unbearable. Each time, DNA tests and fingerprints proved them wrong. As recently as 2024, a woman made aggressive posts in a Facebook group called “Memories of Cherrie Mahan,” claiming to be the long-lost girl. She was removed from the group. Her claims dismissed. Another false hope. Another wound reopened.

Although Pennsylvania law allowed Janice to have Cherrie declared legally dead seven years after her disappearance, she waited thirteen years before filing the petition. In November 1998, a Butler County judge officially declared Cherrie Ann Mahan deceased. Janice donated the $50,000 reward fund to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Cherrie’s trust fund went to her younger brother, Robert, who’d been born four years after his sister vanished.

But legal declarations don’t erase mothers’ hope. They don’t stop the watching. The waiting.

To this day, Janice McKinney still lives in that same area. Still thinks about that Friday afternoon. Still hears the sound of gravel under school bus tires and feels her stomach drop.

The Investigation That Never Stops

For forty years, the Pennsylvania State Police have pursued this case with a persistence that borders on obsession. Thousands of leads. Thousands of interviews. Countless searches across Butler County and beyond.

In January 2011, police received what they called “potentially crucial” information. It came from someone who’d known Cherrie. Someone who provided details specific enough that investigators believed it could lead them to “a known specific actor or actors.” They declined to elaborate publicly, but they did say one thing that chilled everyone who heard it: the information suggested Cherrie was unlikely to still be alive.

That lead, like so many others, eventually went cold. No arrests were made. No body was found. The case remained open.

Then, in 2025—forty years after that February afternoon—something changed.

In August, a private investigator offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to the resolution of Cherrie’s case. New tips came in. Tips that investigators deemed credible enough to act on.

In October 2025, law enforcement descended on South Buffalo Township in Armstrong County, about forty-five minutes from where Cherrie disappeared. The area was remote—river camps, a few scattered houses, dirt roads leading into nowhere. Investigators began digging. Searching areas that, in 1985, would have been perfect places to hide something you never wanted found.

Local resident Darlene Elash watched the activity and told reporters, “This is a dirt road back into this area. There’s a little village on the other end. You’re out in the middle of nowhere, yes. There are the woods all around us and the river behind us”.

As of late October 2025, it’s unclear what, if anything, was found. Sources indicated that future searches would happen because the area was so vast. The investigation continues. Active. Ongoing. Still searching for answers after four decades.

State police acknowledge that the amount of time that’s passed makes this case extraordinarily difficult to solve. There’s no prime suspect. But there are persons of interest. People being actively investigated. People who may know what happened on Cornplanter Road that day.

The Legacy Written In Missing Faces

What happened to Cherrie Mahan changed America in ways most people don’t realize.

Before February 22, 1985, missing children weren’t front-page news unless they came from prominent families. There wasn’t a national database. There wasn’t a coordinated effort. There wasn’t a system for getting a child’s face in front of millions of people quickly.

Cherrie’s case helped change that.

When the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children—founded just the year before, in 1984—chose Cherrie as their very first featured missing child, they pioneered something revolutionary. They put her face on postcards and mailed them to homes across the country. They created the “Have You Seen Me?” campaign that would eventually expand to milk cartons, billboards, and eventually digital media.

That eight-year-old girl in her gray coat became the face of a movement. Her disappearance helped push through legislation. Helped establish protocols. Helped create the infrastructure that now exists to search for missing children.

Every time you see an AMBER Alert on your phone, Cherrie Mahan is part of why that system exists. Every age-progressed photo of a long-missing child, every coordinated search effort, every public awareness campaign—they all trace their lineage back to cases like hers. To communities that refused to forget. To mothers who refused to stop searching.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has helped recover thousands of children since its founding. Each one of those recoveries stands on the foundation built by cases like Cherrie’s. By the advocacy that came from tragedy. By the refusal to accept that children could just disappear without someone, somewhere, caring enough to look.

But for all that legacy, for all those other children who were found, Cherrie herself remains missing. The poster with her face has been updated over the years with age-progressed photographs showing what she might look like as a teenager, as a woman in her twenties, in her thirties, now in her forties. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children’s current poster shows her age-progressed to 44 years old, though she would now be 49 if she’s still alive.

The gray coat has long since rotted away somewhere. The blue leg warmers dissolved into nothing. The beige boots worn to dust. But the image of that eight-year-old girl, frozen in time, continues to circulate. Continues to ask its silent question.

Have you seen me?

The Questions That Have No Answers

Who was driving that blue van? Where did they take Cherrie? Why did they choose that particular afternoon, that particular road, that particular child ?

Was it someone who knew the bus route? Someone who’d been watching, waiting, planning? Or was it a terrible coincidence—wrong place, wrong time, a predator who happened to be passing through rural Pennsylvania that day ?

Janice McKinney has her suspicions. She’s said she doesn’t believe Cherrie’s biological father—a man who raped her when she was just sixteen—was directly responsible. But she suspects “the people he knows” might have been involved. Police have interviewed him. He denies any connection. No evidence has ever linked him or his associates to the disappearance.

In 2011, when that “potentially crucial” information came in from someone who’d known Cherrie, it seemed like answers might finally emerge. But that lead, like everything else, dissolved into more questions. More dead ends. More sleepless nights for everyone who’s carried this case in their hearts for four decades.

The 2025 dig in Armstrong County raised hopes again. Maybe this time. Maybe after forty years, something would finally be found. Some piece of evidence that had waited in the Pennsylvania soil all this time, patient and silent, ready to tell its terrible truth.

But even if that evidence exists, even if it’s found, it won’t change the fundamental horror of what happened. It won’t give Janice back those forty years. Won’t let her hear her daughter’s voice again. Won’t undo the fifty seconds that rewrote her entire life.

Fifty Seconds That Echo Forever

Think about how long fifty seconds actually is. Count it out. One Mississippi. Two Mississippi. Three Mississippi.

It’s the time it takes to walk from a school bus to a house. The time it takes to climb a gentle hill on a gravel driveway. The time it takes for a child to think about the playdate waiting for her. To hum a song. To adjust a backpack. To take one last look at the winter sky before stepping inside to warmth.

Fifty seconds shouldn’t be enough time to change everything. But it was.

In fifty seconds, a mother lost her daughter. A community lost its innocence. A nation gained awareness of a horror that had been happening in shadows for too long.

That school bus still runs the same route. Different bus now. Different driver. Different children climbing on and off at Cornplanter Road. But the stop is still there. The driveway is still there. The house is still there.

What isn’t there is an eight-year-old girl in a gray coat and blue leg warmers. What isn’t there is the sound of small feet on gravel. What isn’t there is “I love you” being said one more time.

On February 22, 2025, Cherrie’s case marked its 40th anniversary. Vigils were held. Stories were shared. Her mother spoke about never giving up hope, even as the years have etched their weight into her face. Even as her daughter—if she’s alive—would now be a woman of 49, possibly with children of her own, possibly living a life somewhere under another name, possibly with no memory of that Friday afternoon.

Or possibly none of those things. Possibly gone in those first terrifying minutes after stepping off that bus. Possibly never given the chance to grow up, to have children, to grow old.

The not knowing is its own special torture. It’s the question that plays on repeat. The hope that refuses to die even as logic says it should. The mother who still watches out windows. Who still tenses when she hears school buses. Who still sees that gray coat in her dreams.

What The Blue Van Took

When that vehicle drove away from Cornplanter Road on February 22, 1985, it took more than just one little girl.

It took a mother’s future. All those moments that should have been—first days of high school, prom dresses, graduation, wedding dances, grandchildren. All of it stolen in the time it takes to microwave a meal.

It took a community’s sense of safety. After Cherrie disappeared, parents in Butler County started walking their children to and from bus stops. Started watching from windows. Started teaching their kids about stranger danger in ways that previous generations never had to.

It took a brother’s chance to grow up with his sister. Robert was born four years after Cherrie vanished, into a household haunted by her absence. He inherited her trust fund, but he never got to inherit her memories. Never got to know what kind of person she would have become.

And it took from all of us, really. Everyone who’s ever looked at that missing poster. Everyone who’s ever wondered what happened on that hill. Everyone who’s ever felt their stomach tighten when their own child is thirty seconds late coming home from school.

Because Cherrie’s story is every parent’s nightmare. It’s the thing we don’t want to think about but can’t stop thinking about. It’s the reason we hold our children a little tighter. Check on them one more time. Tell them “I love you” even when we’re running late.

It’s the reminder that safety is an illusion. That horror doesn’t need darkness or isolation. That it can happen in fifty seconds on a Friday afternoon, on a road you’ve traveled a thousand times, in a place you thought was home.

The Search Continues

As of November 2025, the Pennsylvania State Police continue to investigate Cherrie Mahan’s disappearance. The case remains open. Active. The tip line is still operational. The hope—however faint—remains that someone, somewhere, knows something.

Maybe someone saw that blue van that day and remembers more than they realized. Maybe someone heard something years ago that didn’t make sense then but makes sense now. Maybe someone is finally ready to tell the truth.

The age-progressed photos show a woman with Cherrie’s features matured by time. Dark hair. Serious eyes. The face of someone who’s lived forty years. If she’s out there. If she survived. If she somehow doesn’t know who she really is.

Janice McKinney is now in her late fifties. She’s spent more of her life searching for her daughter than she spent raising her. The math on that is cruel. Eight years of motherhood. Forty years of grief.

But she hasn’t stopped. Won’t stop. Because that’s what mothers do. They wait. They hope. They keep the porch light on even when logic says no one’s coming home.

Somewhere out there, someone knows what happened in those fifty seconds. Someone knows where that blue van went. Someone knows why an eight-year-old girl never made it up her own driveway.

And until that someone speaks, Cherrie Mahan remains what she’s been for forty years: a question without an answer. A child frozen at age eight. A poster that asks us all to remember. To look. To care.

The Door That Never Opened

There’s a moment that Janice McKinney has relived countless times. It’s the moment she realized something was wrong. The moment she walked down that driveway calling her daughter’s name. The moment she reached the road and saw nothing.

That moment has never ended. It’s stretched across four decades. Across thousands of sleepless nights. Across every February 22nd that comes around and marks another year of absence. Another year of questions.

The door that should have opened that afternoon has stayed closed. The footsteps that should have echoed up that driveway have remained silent. The “I love you” that should have been said when Cherrie walked through her front door was never spoken.

In its place is only this: a story that America won’t forget. A case that refuses to close. A little girl in a gray coat and blue leg warmers who stepped off a school bus fifty feet from safety and walked into a mystery that has consumed families, investigators, and advocates for forty years.

She got off the school bus 150 feet from home. Her mother was waiting by the window. But Cherrie never walked through that door.

And somewhere in Pennsylvania—in the woods, in the water, in the memory of someone who’s kept a terrible secret—the answer to what happened in those fifty seconds remains buried.

Still waiting to be found. Still waiting to bring a little girl home.

The Theories That Haunt The Night

For forty years, investigators, journalists, true crime enthusiasts, and armchair detectives have tried to piece together what happened in those fifty seconds. Each theory carries its own weight of horror. Each one explains some pieces while leaving others maddeningly out of reach.

Theory One: Someone She Knew

From the very beginning, investigators believed Cherrie most likely knew her abductor. The reasoning was chillingly simple: an eight-year-old girl in 1985 wouldn’t typically get into a vehicle with a complete stranger, even in rural Pennsylvania where trust ran deeper than in cities. She’d been taught basic safety. She knew not to talk to people she didn’t recognize.

But if someone familiar called to her from that blue van—a neighbor, a friend of the family, someone she’d seen around—she might have approached without fear. Might have accepted an offer of a ride up that hill. Might have climbed inside believing she was safe.

This theory gained weight in 2011 when police received that “potentially crucial” information from someone who’d known Cherrie. Someone who could point investigators toward “a known specific actor or actors.” The fact that this person knew the child suggested the abductor moved in Cherrie’s circles, however peripherally.

Janice McKinney has long held her own version of this theory. While she doesn’t believe Cherrie’s biological father—the man who raped her when she was sixteen—was directly responsible, she believes “the people he knows” were involved. She’s mentioned motorcycle gang connections. Whispered about grudges and revenge. Suggested that Cherrie’s disappearance might have been about hurting Janice herself, about making her pay for seeking child support, about punishing her for trying to hold him accountable.

In 2023 and 2025, new allegations emerged involving neighbors, including someone named John Montgomery. Letters were exchanged with a man named William “Buddy” Montgomery, a convicted sex offender currently in prison, who began communicating with Janice. Buddy has denied involvement, but investigators continue pursuing these leads, trying to separate truth from the desperate grasping at answers that happens in cold cases.

One particularly disturbing letter Janice received claimed Cherrie had been killed by friends of her biological father—members of a Quaker cult who helped “make Cherrie disappear” to help him evade child support payments. The specificity was chilling. The cruelty was breathtaking. But like so many other leads, it dissolved into smoke when investigators tried to verify the details.

Theory Two: The Random Predator

The alternative is somehow worse because it suggests no reason at all. No motive beyond opportunity. No connection beyond proximity.

In this scenario, someone was driving through Butler County that February afternoon. Maybe they lived there. Maybe they were just passing through. Maybe they’d been trolling rural roads looking for exactly what they found—a child alone for just long enough.

They saw the school bus stop. Saw the little girl in the gray coat turn away from the other children and start walking up that hill. Saw their chance. Took it.

The fact that ransom was never demanded strongly suggests this wasn’t about money. Investigators quickly ruled out kidnapping for financial gain. Which means if Cherrie was taken by a stranger, it was for far darker reasons.

In 1994, authorities investigated a Massachusetts man suspected of kidnapping and killing two children, wondering if Cherrie might have been another victim. The investigation led nowhere. He was ruled out.

But how many other predators were operating in Pennsylvania in the 1980s? How many other men were driving vans, watching school buses, waiting for opportunities? The question is as vast as it is horrifying.

Theory Three: The Accident Cover-Up

A smaller contingent of investigators and theorists have wondered if what happened wasn’t an abduction at all, but an accident that someone panicked and covered up. Maybe Cherrie was struck by a vehicle on that driveway. Maybe someone driving recklessly on Cornplanter Road hit her, panicked, put her in their vehicle and drove away, too terrified of the consequences to call for help.

This theory struggles to explain the blue van with the skier mural—why would someone intentionally park near a school bus stop if they were just an accidental killer? But in the chaos of cold cases, even unlikely scenarios get examined. Every angle gets explored.

Theory Four: She’s Still Alive

It’s the hope that Janice McKinney can’t quite let go of, even after forty years. Even after age-progressed photos showing her daughter as a middle-aged woman. Even after logic and statistics scream otherwise.

What if Cherrie was taken by someone who wanted a child? Someone who couldn’t have children of their own, who saw that little girl and decided to make her theirs? What if she was raised under a different name, in a different state, with no memory of Janice or Pennsylvania or who she really was ?

It would explain why her body was never found. Why there’s been no evidence of violence. Why the case has remained so utterly without physical clues.

Several women have come forward over the years claiming to be Cherrie. Each time, DNA tests and fingerprint comparisons have proven them wrong. Pennsylvania State Police maintain Cherrie’s fingerprints from when she was eight years old, and Trooper Christopher Walsh has personally verified alleged sightings in Pittsburgh, matching fingerprints only to conclude the women weren’t Cherrie Mahan.

In 2024, a woman made aggressive posts in the “Memories of Cherrie Mahan” Facebook group, insisting she was the lost girl. She was removed. Her claims dismissed. Another false hope. Another wound reopened for Janice.

But the statistical reality is brutal: most children who are abducted by non-family members are killed within the first three hours. The 2011 information suggesting Cherrie is “unlikely to still be alive” aligns with this grim truth.

Still, Janice waits. Still, she hopes. Because that’s what mothers do when the alternative is unbearable.

The Evidence That Wasn’t There

One of the most frustrating aspects of Cherrie Mahan’s case is the almost complete absence of physical evidence. No body. No clothing. No backpack. No witnesses to the actual abduction. No tire tracks or footprints that couldn’t be explained away by the dozens of people who used that road every day.

The bloodhounds that searched the area in the hours after Cherrie disappeared couldn’t pick up a sustained trail. They’d track to the end of the driveway and then lose the scent, suggesting Cherrie had been put into a vehicle almost immediately.

The blue van with the skier mural should have been the smoking gun. Something that distinctive should have been easy to find. Multiple witnesses saw it. Described it. Yet despite examining numerous similar vans over four decades, despite following hundreds of leads, that exact vehicle has never been conclusively identified.

When police found Donna Patterson’s blue 1976 Dodge van with a skier mural, it seemed like the case might break wide open. But the alibi was ironclad—it had been parked at a steel corporation when Cherrie vanished. It wasn’t the right van.

Which means either witnesses were mistaken about the details of the mural (possible but unlikely given multiple corroborating accounts), or there was another nearly identical van that somehow vanished just as completely as Cherrie did.

The 2025 dig in South Buffalo Township raised hopes that finally, after forty years, some physical evidence might emerge. The area being searched—remote river camps, dense woods, areas that would have been perfect for hiding something in 1985—represents the kind of location investigators have long suspected might hold answers.

But as of late October 2025, no public announcements have been made about findings. The investigation continues. The digging continues. The waiting continues.

The Legislation Born From Loss

While Cherrie Mahan was never found, her disappearance helped reshape how America responds to missing children. The impact rippled through legislation, public awareness, and law enforcement protocols in ways that continue to this day.

The Foundation Was Already Forming

By the time Cherrie disappeared in February 1985, Congress had already begun responding to the crisis of missing children. The Parental Kidnapping Prevention Act passed in 1980, addressing custody disputes that led to child abductions. The Missing Children Act followed in 1982, requiring the FBI to record missing children in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database to aid law enforcement agencies nationwide.

Then in 1984—just one year before Cherrie vanished—Congress passed the Missing Children’s Assistance Act, which established the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) as a resource for families, law enforcement, and communities dealing with missing children cases.

NCMEC was brand new when Cherrie disappeared. Still finding its footing. Still figuring out how to serve its mission. And they chose Cherrie Mahan as their very first featured missing child.

The “Have You Seen Me?” Revolution

The decision to put Cherrie’s face on postcards and mail them to homes across America was revolutionary. Before this, missing children were local news stories that rarely traveled beyond their immediate regions. Information moved slowly. Coordination between jurisdictions was minimal. A child could disappear in Pennsylvania and no one in California would ever know to look for them.

The “Have You Seen Me?” campaign changed that. Suddenly, millions of Americans were opening their mail and seeing Cherrie’s eight-year-old face staring back at them. Reading the details of what she was wearing. Seeing the description of that blue van with the skier mural. Being asked to look, to remember, to call if they knew anything.

The campaign expanded to milk cartons—a strategy that became iconic in 1980s America. By 1985, the first year Cherrie’s case was active, approximately 700,000 American children were reported missing each year. The milk carton campaign, inspired by cases like Cherrie’s, meant that every breakfast table became a potential tip line. Every parent pouring cereal for their kids saw those faces and held their own children a little tighter.

The Behavioral Shift

Trooper James Hall, who worked Cherrie’s case, noted a fundamental change in parenting behavior in Butler County after her disappearance. “In the 1980s, parents didn’t take their kids to and from the bus stop like they do today,” he explained. The assumption had been that children were safe in their own neighborhoods, on roads they traveled every day.

Cherrie’s case shattered that assumption. Suddenly parents were walking their children to bus stops and waiting there until the bus arrived. They were watching from windows as their kids walked home. They were teaching stranger danger and what to do if someone approached them. They were having conversations that previous generations never needed to have.

This behavioral shift rippled across America. Every missing child case that made national news—and after NCMEC’s founding, more and more did—reinforced the message that safety couldn’t be assumed. That predators existed. That children needed to be watched, protected, taught.

The System That Evolved

Today’s AMBER Alert system—the notifications that hit our phones when a child goes missing, providing immediate descriptions and information to millions of people simultaneously—is the direct descendant of programs pioneered by cases like Cherrie’s. The technology is different, but the concept is the same: get information out fast and wide, because every minute matters.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has assisted in the recovery of more than 320,000 missing children since its founding in 1984. Age-progression technology, where experts use photographs to show what a missing child might look like years or decades later, has become standard practice. DNA databases, fingerprint registries, coordinated search protocols—all of these evolved from the desperate need to do better after cases like Cherrie’s.

But for all the children who’ve been found, for all the systems that have improved, for all the legislation that’s been passed, Cherrie herself remains missing. The poster child for missing children advocacy is still missing. The irony is as painful as it is profound.

The Community That Carries The Weight

For the residents of Winfield Township and Butler County, Cherrie Mahan’s disappearance isn’t history. It’s not a cold case file or a true crime podcast episode. It’s the thing that divided their lives into before and after.

“People really feel for this community,” said an investigator at the 40th anniversary vigil in 2025. Hundreds of people turned out to the Saxonburg Veterans of Foreign Wars post that evening. Forty years later, and the community still gathers to remember. Still hopes for answers.

Every year around the anniversary, tips start coming in. People remember something. People reconsider something they saw. People’s consciences finally overcome their fear or complicity or indifference. Investigators say the volume of tips increases substantially around February 22nd each year, as the case makes news again, as people are reminded.

For those who live in the area, daily life carries constant reminders. That driveway is still there. The road where the school bus stopped is still traveled. Children still get off buses in Winfield Township, though their parents now wait with them in ways that previous generations didn’t.

There’s a heaviness that comes with living in a place where something terrible happened and was never resolved. Where every blue van causes a double-take. Where every missing child case anywhere in America carries echoes of the one that happened right here. Where a mother still lives among them, still carrying a grief that’s incomprehensible in its duration.

The Investigators Who Never Stopped

The Pennsylvania State Police have maintained active investigation of Cherrie Mahan’s disappearance for forty years. Officers have come and gone, retired and been replaced, but the case file remains open. The commitment remains unshaken.

Trooper James Hall worked the case for years before passing it to Trooper Christopher Walsh, who investigated for two years until his promotion to corporal. Now Trooper Robert DeLuca handles what continues to be an active investigation, still receiving tips, still pursuing leads, still searching.

“Anyone who was implicated remains a suspect until we find evidence to the contrary,” stated Trooper Long, one of the many investigators who’ve worked Cherrie’s case over the decades. It’s a commitment that speaks to both the thoroughness of the investigation and the frustration of having no clear answers.

The investigative file on Cherrie Mahan is massive. Thousands of tips. Thousands of interviews. Hundreds of potential suspects examined and cleared or kept on the list of persons of interest. The amount of work that’s gone into this case is staggering, and yet it hasn’t been enough.

The 2025 dig in Armstrong County represents the latest in a long line of searches based on new information. Investigators used modern tools and techniques that didn’t exist in 1985. Ground-penetrating radar. Cadaver dogs with training that’s evolved over decades. Forensic methods that can extract information from the smallest traces.

But even modern technology can’t overcome the fundamental problem: without knowing where to look, even the best tools are just shots in the dark.

The Psychology Of A Predator

What kind of person takes an eight-year-old child off a rural Pennsylvania road in broad daylight?

Criminal psychologists who’ve studied cases like Cherrie’s identify several characteristics that her abductor likely possessed:

Familiarity with the area: The timing was too perfect to be random chance. The abductor knew when that school bus ran. Knew where it stopped. Knew that there would be a moment when Cherrie would be alone. This suggests someone local or someone who’d been watching and planning.

Confidence bordering on arrogance: To park near a school bus stop, to take a child within minutes of her getting off that bus, within 150 feet of her home—that requires either desperation or a belief that you won’t be caught. The lack of physical evidence suggests this wasn’t a panicked, sloppy crime. It was executed efficiently.

Likely previous offenses: First-time offenders rarely pull off abductions this clean. The absence of evidence, the quick execution, the ability to disappear without a trace—these suggest someone who’d practiced. Who’d thought through the logistics. Who might have done this before or would do it again.

The investigation into William “Buddy” Montgomery—a convicted sex offender who began exchanging letters with Janice McKinney in recent years—exemplifies how investigators profile potential suspects. His criminal history, his connections to the area, his willingness to engage with the case even while denying involvement—all of these factors make him someone worth investigating, even decades later.

But profiling can only go so far. Without evidence, without witnesses to the actual abduction, even the most detailed psychological profile is just educated guessing.

The Other Children Who Disappeared

Cherrie Mahan wasn’t the only child who vanished in America in 1985. She wasn’t even the only one in Pennsylvania that year. But she became the face of the missing children crisis because of timing, because of NCMEC’s founding, because her mother fought so hard to keep her story alive.

In the 1980s, approximately 700,000 children were reported missing in America each year. Most were runaways or custody disputes. But a terrifying percentage—thousands of children annually—were stranger abductions. Cases where a child simply disappeared, taken by someone outside their family, often never to be seen again.

The milk carton campaign that Cherrie’s case helped inspire featured dozens of children’s faces. Some were eventually found. Some aged out of being children while still missing. Some were found deceased. And some, like Cherrie, simply remained question marks—faces on cartons, posters on walls, age-progressed photos in databases.

Each one represents a family destroyed. A mother or father or sibling carrying impossible grief. A community grappling with the knowledge that evil walked among them and they didn’t stop it.

Cherrie’s case stands out not because it’s unique in its horror, but because it became the catalyst. Because it happened at exactly the right moment to drive change. Because her mother refused to let her daughter be forgotten.

What The Van Knows

Somewhere, that blue van with the skier mural still exists. Or it did, at some point. Vehicles don’t just disappear.

Maybe it was repainted immediately after February 22, 1985. Maybe the distinctive mural was covered over, transforming it into just another anonymous van on American roads. Maybe it was sold, dismantled, sent to a junkyard and crushed into a cube of metal, destroying whatever forensic evidence might have been inside.

Maybe it’s still in someone’s garage. Still recognizable. Still carrying secrets in its wheel wells and carpet fibers.

Or maybe it never existed the way witnesses remember. Human memory is notoriously unreliable, especially under stress, especially when multiple people are comparing notes and unconsciously conforming their memories to match each other’s. Maybe the van was a different color. Maybe the mural was different. Maybe details got confused in the chaos of that afternoon.

But multiple witnesses saw it. Described it independently. The detail about the skier on the mountain was too specific, too unusual, to be a mass hallucination.

So the van was real. And somewhere, someone knows what happened to it. Someone drove it away from Cornplanter Road that day. Someone parked it somewhere. Someone either kept it or got rid of it.

And if investigators could find that van, even forty years later, even if it’s been sitting in a barn or rusting in a field—modern forensic technology could potentially extract evidence that 1985 technology couldn’t. DNA. Fibers. Trace evidence that could finally, finally answer the question of what happened to Cherrie Mahan.

It’s one of the most frustrating aspects of the case. The key piece of evidence was seen by multiple people. Described in detail. And yet it might as well have vanished into thin air.

The Hope That Refuses To Die

In November 2025, as this story is being written, Cherrie Mahan would be 49 years old. Old enough to have grandchildren. Old enough to have lived an entire adult life—career, relationships, joys and sorrows and all the ordinary moments that make up a human existence.

If she’s alive.

The age-progressed photos show a woman with Cherrie’s features matured by time. Dark hair, maybe graying. Lines around the eyes. The weight of years visible in her face. NCMEC updates these photos periodically, using algorithms and artistic skill to imagine how an eight-year-old girl might look as the decades pass.

Janice McKinney, now in her late fifties, still looks at those photos. Still searches crowds for her daughter’s face. Still answers every tip, investigates every lead, holds onto hope even when logic says she shouldn’t.

At the 40th anniversary vigil in February 2025, Janice spoke about never giving up. About knowing, somehow, that one day she’ll have answers. About believing that someone, somewhere, will finally tell the truth.

“I am not going to rest until I know exactly what happened to her,” she told reporters. Forty years of not resting. Forty years of wondering. Forty years of that door staying closed.

The vigil drew hundreds of people. Community members who were children themselves when Cherrie disappeared, now bringing their own children to remember. Law enforcement officers who’ve worked the case. Advocates for missing children. True crime followers who’ve kept Cherrie’s story alive online. People who never met Cherrie but feel connected to her story in ways they can’t quite articulate.

Because Cherrie’s case represents something larger than one missing girl. It represents every parent’s nightmare. Every community’s vulnerability. Every system’s failure. And every reason to keep fighting for answers no matter how long it takes.

The Message In The Mailbox

Forty years ago, millions of Americans opened their mailboxes and found Cherrie Mahan looking back at them. That eight-year-old face on a postcard. Those words: “Have You Seen Me?”.

Most people glanced at it and threw it away. Some pinned it to bulletin boards or refrigerators for a while before it got lost in the shuffle of daily life. A few called in tips—most worthless, but each one investigated anyway because you never know.

But the act of putting that postcard in those mailboxes changed something fundamental. It said: This child matters. This family’s grief matters. We all have a responsibility to watch, to remember, to care.

Today, digital technology has replaced postcards. AMBER Alerts hit our phones with the urgency of air raid sirens. Social media spreads missing persons cases in hours instead of weeks. The mechanics have changed, but the message remains the same.

Have you seen me?

Are you looking?

Do you remember?

Cherrie Mahan asked those questions first. Her face on that first NCMEC poster established a precedent that thousands of missing children have since followed. Her disappearance helped build the infrastructure that’s recovered hundreds of thousands of other children.

But she’s still missing. The first child featured is still unfound. The question she asked in 1985 still echoes unanswered.

Fifty Seconds. Forty Years. One Question.

The mathematics of tragedy are simple and brutal. Fifty seconds to disappear. Forty years of searching. One question that remains unanswered.

What happened to Cherrie Mahan?

Somewhere, someone knows. Maybe it’s the person who was driving that blue van. Maybe it’s someone who saw something that day and stayed silent out of fear or complicity. Maybe it’s someone who heard a confession or a boast or a slip of the tongue and never reported it. Maybe it’s someone who helped cover up what happened, who buried evidence or provided a false alibi or kept a terrible secret.

Someone knows.

And until that someone speaks, Cherrie remains frozen at eight years old. Remains a question mark. Remains a poster on a wall, a file in a database, an age-progressed photo that may or may not look anything like the woman she would have become.

Her mother remains in her late fifties, having spent the majority of her life searching. Having buried her daughter legally but never emotionally. Having said “I love you” one last time that morning and never gotten to say it again.

Her community remains marked by that February afternoon. Remains changed by the knowledge that one of their own was taken and never returned. Remains vigilant in ways they never had to be before 1985.

And America remains indebted to a case that helped change how we search for missing children. Remains better equipped because of systems built on the foundation of this tragedy. Remains aware in ways we weren’t before Cherrie’s face appeared on that first postcard.

The Ideal Outcome

At that 40th anniversary vigil, an investigator spoke about the ideal outcome: “A, that Cherrie is found, and B, that whoever is responsible is brought to justice”.

Both parts matter. Finding Cherrie—whether alive or deceased, whether whole or in pieces—would give Janice what every parent of a missing child desperately needs: certainty. An end to the not-knowing. A place to grieve or a reunion beyond imagining.

And justice—making someone answer for what they did, making them face the consequences, making sure they can never do it again—would serve something larger than one family’s peace. It would send a message that forty years doesn’t erase culpability. That we don’t forget. That we don’t give up.

But ideal outcomes are rare in cases this old. Evidence degrades. Witnesses die. Memories fade. Trails go cold beyond cold, into frozen territory where even the most determined investigators struggle to make progress.

Still, the digging continues. In Armstrong County. In databases. In memories. The Pennsylvania State Police continue investigating. The tips continue coming in around each anniversary. The age-progressed photos continue being updated. The hope continues, however faint.

Because the alternative—accepting that Cherrie will never be found, that her abductor will never be identified, that this question will remain unanswered forever—is unbearable.

A Mother Waiting By A Window

There’s an image that haunts everyone who knows this story. It’s Janice McKinney standing at her kitchen window on February 22, 1985, listening to the school bus arrive, expecting to hear the sound of small feet on gravel any second.

And the seconds tick by. And the sound never comes. And she walks to the window and looks down that driveway and sees nothing. And the panic starts to rise. And she calls her daughter’s name. And only silence answers.

That image—that moment when hope turned to confusion turned to fear turned to horror—is where Cherrie Mahan’s story lives. It’s the moment that divided everything into before and after. It’s the moment that launched forty years of searching. It’s the moment that helped change America’s approach to missing children.

Janice McKinney still lives in that area. Still, in some way, stands at that window. Still waits for footsteps that never came. Still holds onto hope that defies logic but defines motherhood.

She got off the school bus 150 feet from home. Her mother was waiting by the window. But Cherrie never walked through that door.

And somewhere in Pennsylvania—in the ground, in someone’s memory, in evidence that hasn’t been found yet—the answer waits. The truth about what happened in those fifty seconds. The resolution to forty years of searching. The end to a mother’s longest nightmare.

Until that day comes, Cherrie Mahan remains what she’s been since February 22, 1985: a question without an answer. A daughter who never came home. A poster that asks us all to remember.

Have you seen her?

Are you looking?

Do you remember?

Forty years later, we’re still searching for the answer.