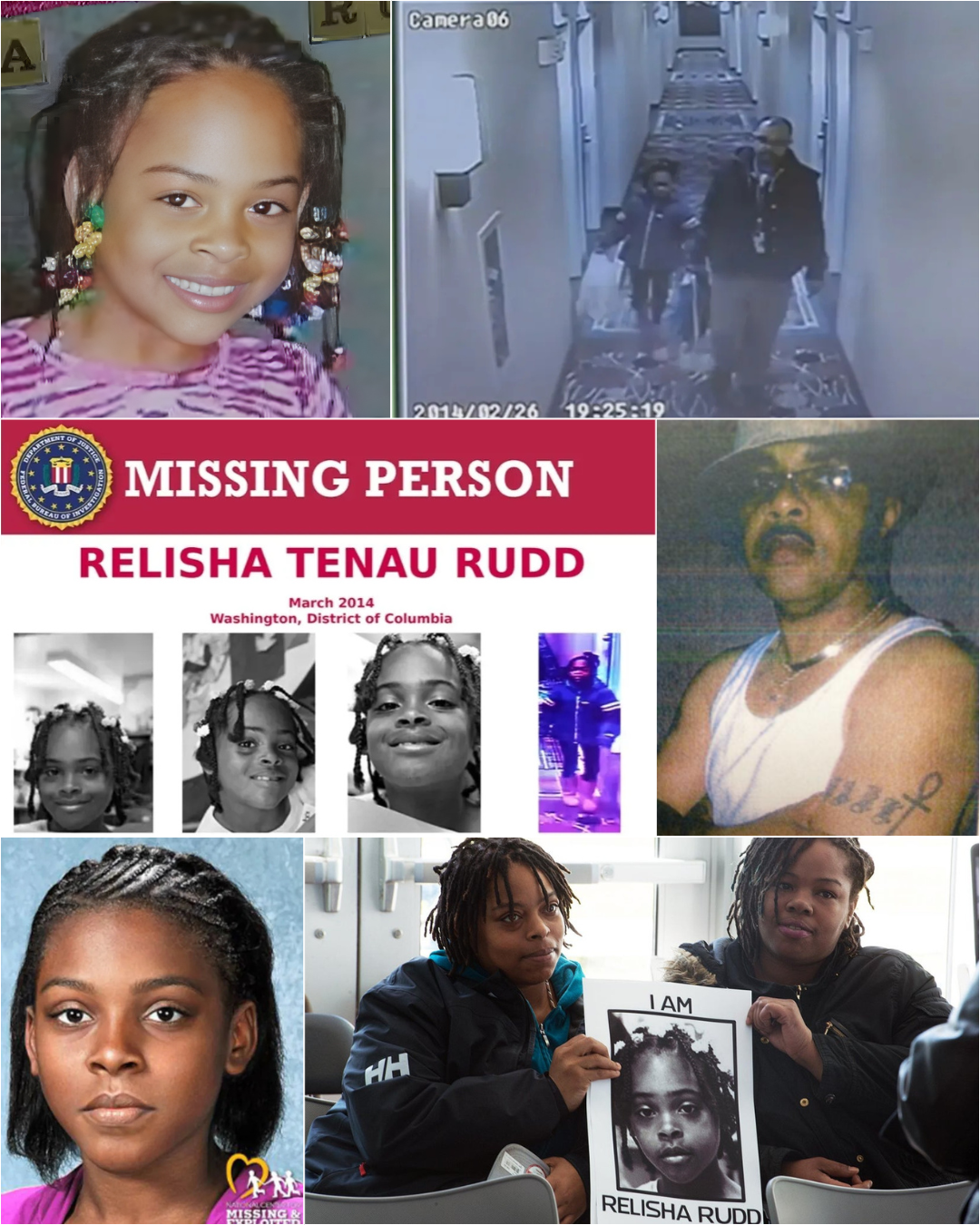

The surveillance footage was grainy, but unmistakable. An 8-year-old girl in pink boots and a purple Helly Hansen jacket walked hand-in-hand with a middle-aged man down a dimly lit hotel hallway. She appeared small beside him, trusting. The timestamp read February 26, 2014. Five days later, on March 1, another camera would capture the same pair at a different motel—this time on New York Avenue in Northeast Washington, D.C. The man left the room later that day. The little girl never did.

That child was Relisha Tenau Rudd, and March 1, 2014, was the last confirmed sighting of her alive. Eleven years have passed since that haunting moment, yet her disappearance remains one of Washington D.C.’s most devastating unsolved mysteries—a case that exposed catastrophic failures in the systems meant to protect vulnerable children and raised uncomfortable questions about whose lives matter when a child goes missing.

A Childhood Marked by Instability

Relisha was born on October 29, 2005, into circumstances no child should endure. By the time she was eight, she had already experienced more upheaval than many people face in a lifetime. Her mother, Shamika Young, had spent years cycling through foster care herself, carrying the trauma of her own fractured childhood into motherhood. Relisha’s stepfather, Antonio Wheeler, worked construction jobs out of state, leaving the family for weeks at a time. Her biological father had his own troubled history—one source noted he was later convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

For more than a year before her disappearance, Relisha lived with her mother, stepfather Antonio Wheeler, and her two younger brothers at DC General Family Shelter in Southeast Washington. The massive facility, a converted hospital that once served the city’s medical needs, had been repurposed into emergency housing for homeless families. But it was never designed to be a home. The shelter was overcrowded—at times housing up to 600 children—with bedbugs crawling through dirty mattresses, broken showers, and no playground where children could safely play. It was an environment of desperation, where dignity went to die and predators could hide in plain sight.

Despite everything, those who knew Relisha remembered a joyful child. She loved reading and math. She stood up fiercely for her younger brothers when anyone disrespected them. She had a radiant smile that lit up rooms, even in the darkest of places. “Relisha brought everyone joy,” Wheeler would later say, his voice heavy with the weight of what he had lost.

The Janitor Who Became “Doctor Tatum”

Kahlil Malik Tatum was 51 years old when he entered Relisha’s life. A janitor contracted to work at DC General through the nonprofit Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness, Tatum had a criminal record that should have immediately disqualified him from working near vulnerable families. Between 1993 and 2003, and again from 2004 to 2011, he had been imprisoned for burglary, larceny, and breaking-and-entering—spending a combined 17 years behind bars. Yet somehow, he passed through the hiring process and found himself working in a facility teeming with children whose parents had few resources and even fewer options.

Tatum knew how to identify vulnerability. He understood which families were struggling the most, which mothers were overwhelmed, which fathers were absent. He began by offering small kindnesses—helping children get breakfast in the shelter cafeteria when their parents were still sleeping, offering rides, giving gifts. Witnesses later reported that Tatum was known for “inappropriately fraternizing with shelter residents” and “paying particular attention to young girls”. Some parents noticed and turned him away. Relisha’s mother did not.

The relationship between Tatum and Relisha’s family deepened over time. He bought Relisha a tablet for Christmas. He took her to see Disney on Ice, an outing that would have seemed like magic to a child living in a shelter. He took her shopping, bought her gifts, spent time with her—always under the premise that she was playing with his granddaughter. Her family came to trust him. In a place where trust was a rare commodity, Tatum became something like a benevolent figure, someone willing to help lighten the impossible burden of raising children in poverty.

“He was getting too fond of Relisha,” Wheeler’s grandfather had warned, urging Shamika to keep the janitor away from the little girl. But the warning went unheeded.

By February 2014, Relisha was spending nights away from the shelter with Tatum, supposedly staying with his granddaughter. Her mother gave permission, believing her daughter was being cared for. No one at the shelter stopped it, despite a strict no-fraternization policy that prohibited staff from forming personal relationships with residents. The policy was in place. It simply wasn’t enforced.

The Absences That Went Unnoticed

Relisha was a second-grader at Payne Elementary School, a neighborhood school where 55 of the roughly 260 students were also homeless. In February 2014, she stopped showing up. One day became two. Two became a week. A week became more than a month.

When school officials reached out to inquire about Relisha’s mounting absences—eventually totaling more than 30 days—her mother provided a note explaining that the child was sick and under the care of a “Dr. Tatum”. The note was accompanied by a phone number. When officials called, they reached a man who assured them that Relisha was being treated for severe migraines and neurological problems. He promised to provide medical documentation. He said he would meet with school officials to discuss her condition.

But the documentation never came.

On March 19, 2014—eighteen days after Relisha was last confirmed to be alive—a social worker from DC Public Schools named LaBoné Workman went to DC General to meet “Dr. Tatum” in person and retrieve the promised medical paperwork. When he arrived and began asking for Dr. Tatum, shelter staff looked confused. There was no doctor by that name working there. There was only Kahlil Tatum, the janitor.

“Everything kind of collapsed,” Workman would later recall.

In that moment, the deception unraveled. The doctor’s notes had been forgeries. The man caring for Relisha wasn’t a physician treating her illness—he was a convicted felon with a troubling history who had manipulated his way into the family’s trust. By the time authorities realized what was happening, Relisha had already been gone for weeks.

That same day, March 19, DC police initiated a missing persons investigation. By then, the trail was cold.

A Grandmother’s Phone Call

On March 12—one week before anyone reported Relisha missing—her grandmother, Melissa Young, had called Kahlil Tatum. She wanted to ask about the tablet he had bought Relisha for Christmas. It wasn’t working properly, and she wondered if it was still under warranty.

During the conversation, Melissa asked if Relisha was with him. At first, Tatum said no. Then, inexplicably, he changed his story. He told Melissa that yes, actually, Relisha was with him—along with his wife, daughter, and granddaughter. They were all in Atlanta, Georgia, attending some kind of medical retreat or family conference.

Melissa called her daughter Shamika and asked if she knew Relisha was out of town. Shamika said she had told Tatum not to take Relisha on the trip. Yet no one called the police. No one demanded Relisha’s immediate return. Instead, Melissa told Tatum to bring her granddaughter home by Sunday, March 16, for a birthday party.

Tatum never showed up.

The next morning, Tatum called Melissa again. He told her he had taken Relisha to school. But when Melissa checked her calendar, she realized it was a day when school was closed.

Three days later, the truth would begin to emerge. But by then, it was far too late.

The Last Images

As investigators launched their search for Relisha, they quickly uncovered surveillance footage from two hotels in Northeast Washington, D.C.. The first video, dated February 26, 2014, showed Relisha and Tatum walking together down a hallway at a Holiday Inn Express on Bladensburg Road. She was wearing her distinctive pink boots and purple jacket, holding Tatum’s hand. The footage was released to the public by the FBI in a desperate plea for information.

The second—and final—piece of surveillance footage came from March 1, 2014, at a Days Inn on New York Avenue. The video showed Relisha and Tatum entering room 245 together. Hours later, Tatum left the room. Relisha did not.

That motel was known in the neighborhood as a place where people went to disappear—a haven for drug use, prostitution, and criminal activity. Guests later told reporters that felons and people who had lost their homes frequently stayed there, blending into the background, invisible. One hotel clerk confirmed that Tatum had checked into the room on March 1, paying with a Mastercard and arriving in a Chevy SUV.

One witness, a guest at a nearby homeless center, claimed to have seen Relisha around March 1 or 2—not at the hotel, but at the Virginia Williams Homeless Center on Rhode Island Avenue NE, near a Home Depot. That Home Depot, investigators would soon learn, was where Tatum made a chilling purchase.

On March 2—one day after the last confirmed sighting of Relisha—Tatum walked into a store and bought a shovel, lime, and 42-gallon contractor-sized trash bags. These were tools often used to dispose of bodies.

From that moment forward, Relisha Rudd was never seen again.

A Wife Found Dead

On March 20, 2014—the same day Relisha was officially reported missing—investigators made a horrifying discovery. At a Red Roof Inn in Oxon Hill, Maryland, just across the D.C. line in Prince George’s County, they found the body of 51-year-old Andrea Tatum, Kahlil’s wife. She had been shot in the head. Surveillance footage from the motel showed Kahlil and Andrea entering the room together the night before.

Andrea Tatum had been a fixture in her community, known for her generosity and her volunteer work at her local church. She had struggled with drug addiction in the past, a victim of the crack epidemic that devastated so many Black families in Washington, D.C., but she had fought her way to sobriety and remained clean. She worked at an affordable housing facility for gay men and was remembered as someone who helped those in need.

Court records later revealed that Andrea had been unhappy in her marriage and was pursuing a divorce. Some speculated that she had discovered something about Kahlil’s activities with Relisha—something he couldn’t allow her to reveal. Others believed her murder was simply the act of a man spiraling out of control, destroying everything in his path.

Prince George’s County police immediately issued an arrest warrant for Kahlil Tatum, charging him with first-degree murder in his wife’s death. They also issued a warning: Tatum was believed to be armed and dangerous. The FBI added him to their Ten Most Wanted list for murder, offering a $25,000 reward for information leading to his capture. An Amber Alert was issued for Relisha, with Tatum named as her suspected abductor.

But Kahlil Tatum had vanished.

The Search for Relisha

What followed was one of the most extensive searches in Washington D.C.’s history. Police Chief Cathy Lanier mobilized hundreds of officers, cadets, and volunteers to comb through Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens, a sprawling 700-acre nature preserve in Northeast D.C., near the Maryland border. Investigators believed Tatum had spent time there after purchasing the shovel and trash bags.

Dive teams were dispatched into the Anacostia River and the seven small bodies of water within the park. K-9 units searched the grounds. Cadets walked grid patterns on foot, meticulously covering every inch of terrain. Volunteers arrived by the dozens, handing out fliers with Relisha’s face, refusing to give up hope.

The search was, in Chief Lanier’s words, “very technical” and difficult. The park’s dense vegetation and waterways made it nearly impossible to cover completely. Still, authorities pressed on, driven by the faint possibility that they might find Relisha alive—or at least find answers.

On March 31, 2014, searchers acting on a tip made a grim discovery. Inside a shed in Kenilworth Park, they found the body of a man matching Kahlil Tatum’s description. He had died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound—the same weapon used to kill his wife Andrea. An autopsy later confirmed the body was Tatum’s and that he had been dead for at least 36 hours.

With Tatum’s death, the one person who might have been able to tell investigators what happened to Relisha was gone. “A lot of information was gone with him,” one official said.

Despite days of intensive searching in and around Kenilworth Park, no trace of Relisha was ever found. The operation continued for hours even after Tatum’s body was discovered, but it yielded nothing.

“They were pretty sure that she was out there somewhere,” said Derrick Butler, a retired teacher and missing persons advocate who participated in the search, “and they continued to let us search for probably about another 4 or 5 hours”.

But Relisha was nowhere.

Failures at Every Level

In September 2014, six months after Relisha’s disappearance, the District of Columbia released a comprehensive review of the agencies and systems that had come into contact with her and her family. The report identified more than two dozen policy failures and recommended sweeping changes to how schools handle absences, how background checks are conducted for shelter employees, and how staff and residents are monitored for inappropriate relationships.

Yet the report’s conclusion was as stunning as it was frustrating: the District “could not have prevented” Relisha’s disappearance, citing “misleading information provided by Relisha’s family” as a key factor. Critics immediately challenged this finding, arguing that the report failed to hold institutions accountable for their role in allowing a convicted felon to work unsupervised with children and for failing to act quickly when Relisha stopped attending school.

The systemic failures were undeniable. Tatum’s criminal record—17 years in prison for burglary, larceny, and breaking-and-entering—should have disqualified him from working at DC General. Yet he was hired by a contractor without proper screening. The no-fraternization policy that prohibited staff from forming personal relationships with residents was routinely ignored. When Tatum openly gave gifts to children and spent time alone with them, no one intervened.

Relisha’s school absences, meanwhile, piled up for weeks before anyone questioned the validity of “Dr. Tatum’s” medical notes. By the time a social worker finally went to the shelter to investigate, 18 days had passed since anyone had seen Relisha alive. District truancy laws required schools to report students to Child and Family Services after 10 unexcused absences, but Payne Elementary delayed the report to give Shamika Young additional time to collect medical documentation. That delay, well-intentioned or not, cost precious time.

Child and Family Services had also been involved with Relisha’s family, with caseworkers from multiple agencies in contact with them. But those caseworkers, the review found, were not communicating with one another. Critical information fell through the cracks—much like Relisha herself.

A Shelter Demolished, A System Reformed

The shelter where Relisha lived has since been demolished. In 2018, Mayor Muriel Bowser fulfilled her promise to close DC General once and for all, replacing it with smaller, neighborhood-based family shelters designed to provide wraparound services in a more dignified environment. The new shelters—the first three opened in July 2019—feature private rooms for families, on-site social services, employment assistance, and mental health support. They were designed with the lessons of Relisha’s case in mind: that children and families experiencing homelessness deserve safety, dignity, and vigilant protection.

But for Relisha, those reforms came years too late.

A Family’s Anguish and Suspicion

In the aftermath of Relisha’s disappearance, her family became the subject of intense scrutiny and suspicion. Shamika Young, Relisha’s mother, faced withering criticism for allowing Tatum to take her daughter on overnight trips and for failing to report her missing for weeks. At one point, a grand jury was empaneled to investigate possible obstruction of justice charges against her, though no charges were ever filed.

Young defended herself in radio and television interviews, breaking down as she described the impossible grief of losing her first-born child. “Can’t nobody put their feet in my shoes,” she said, her voice cracking. “Don’t nobody know what’s going through my mind and what’s running through my head”. She maintained that she believed Relisha was staying with her grandmother and aunt during the weeks she was missing, and that she had no phone or regular means of contact to check on her.

Antonio Wheeler, Relisha’s stepfather, expressed his own torment. “As a father, you are a protector, and there are times that I failed to protect my own daughter,” he said. “I know the term ‘living a nightmare.’ I’m living one right now”. Wheeler has consistently maintained that he believes Relisha is still alive, clinging to hope even as years have passed without answers.

But Wheeler also cast suspicion on others in the family, making statements that implicated Shamika and her mother Melissa in Relisha’s disappearance. For her part, Shamika claimed she had no contact with the school about Relisha’s absences and that Antonio was the one handling those communications. Melissa, meanwhile, said she believed Relisha was in Shamika’s care during the weeks she was missing.

The family’s conflicting accounts only deepened the mystery and fueled public frustration. In the court of public opinion, Shamika Young became a symbol of parental failure, a mother who had trusted the wrong person and paid an unthinkable price. Yet those who have studied her story more closely paint a more complicated picture—a young woman who herself had been failed by the system, raised in foster care, struggling with poverty and trauma, and lacking the resources and support to protect her children.

“Relisha’s family really was living kind of a cycle of trauma,” said Jonquilyn Hill, who reported an eight-part series on Relisha’s case in 2021 for public radio station WAMU. Both of Relisha’s parents had partly grown up in the foster care system themselves. Although Wheeler lived at the shelter with Young and the couple’s children, he frequently worked in construction out of state, and Young had her hands full with the younger boys. “I do think Khalil Tatum knew who to take advantage of,” Hill said. “I think he knew who to go to, who wouldn’t talk, who wouldn’t know to talk, and who was having particular struggles and issues”.

Theories About What Happened

With Kahlil Tatum dead and Relisha’s body never recovered, investigators and advocates have been left to piece together theories about what happened to the 8-year-old girl.

The most widely accepted theory among law enforcement is that Tatum murdered Relisha shortly after she was last seen on March 1, 2014. The purchase of a shovel, lime, and contractor-sized trash bags the day after her last sighting strongly suggests he planned to dispose of her body. His subsequent murder of his wife and his suicide before police could question him further support this theory.

A senior law-enforcement official told The Washington Post that they suspected Tatum had been sexually exploiting Relisha, possibly trafficking her to others, and may have killed his wife because she discovered his activities. This theory aligns with reports that Tatum was known for inappropriate relationships with young girls at the shelter and that he took Relisha to motels known for prostitution and criminal activity.

Some advocates, including Derrica and Natalie Wilson of the Black and Missing Foundation, believe Relisha may have been sold into sex trafficking and could still be alive. “We believe that someone out there knows something,” Natalie Wilson said. While DC Metropolitan Police detectives have publicly ruled out the sex-trafficking theory, the Wilson sisters and others continue to hold out hope that Relisha survived and is being held somewhere against her will.

Members of Relisha’s family, including her stepfather Antonio Wheeler, have also expressed belief that she is still alive, pointing to the fact that her body has never been found. “I actually believe she’s still alive,” Wheeler said after police searched tunnels beneath DC General in 2018. “They only looked for a body. They found nothing. So why would that tell you she’s not there?”

But the grim reality is that without Tatum alive to provide answers, and without Relisha’s body, the truth may never be known.

The Invisible Children: Missing Black Girls and Media Silence

Relisha Rudd’s case has become emblematic of a larger, more insidious crisis: the systematic erasure of missing Black children from public consciousness. While cases involving missing white children—particularly white girls—dominate national headlines and trigger massive public mobilization, Black children who disappear often receive little more than a passing mention in local news.

This phenomenon, known as “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” describes the disproportionate media coverage given to missing persons cases involving young, white, middle- or upper-class women and girls, while cases involving people of color, particularly Black women and children, are ignored or minimized. The disparity is not subtle. Research has consistently shown that white children receive significantly more media attention when they go missing than Black children, even when the circumstances are identical.

The statistics are sobering. In 2020, nearly 40% of missing children cases reported to the FBI involved Black children, despite Black children representing only 14% of the U.S. child population. Black children go missing at rates dramatically higher than their white peers, yet their cases receive a fraction of the media coverage.

“Black kids go missing at a higher rate than white children, but the coverage is not proportionate,” said Derrica Wilson, co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation. “When you don’t see yourself reflected in the media, when your child’s case doesn’t get the same attention, it sends a message about whose lives matter”.

Relisha’s case received substantial local coverage in Washington, D.C., but it never became a national story in the way that cases like JonBenét Ramsey or Madeleine McCann did. There were no cable news specials dissecting every detail of her life. No celebrity advocates championing her cause. No viral social media campaigns demanding justice.

“The case of Relisha Rudd received little coverage outside of the Washington, D.C., area, leading to criticism that her case receives little attention due to her marginalization as a black girl from an impoverished family,” Wikipedia’s entry on her disappearance notes.

That marginalization—the intersection of race, poverty, and homelessness—made Relisha invisible long before she disappeared. She was a Black child living in a homeless shelter, attending a school where more than half the students had no permanent address. In America’s hierarchy of innocence and victimhood, she ranked near the bottom.

A Documentary Eleven Years in the Making

Every year on October 29, those who remember Relisha Rudd gather to mark what should have been her birthday. In 2017, Washington D.C. officially designated July 11 as Relisha Rudd Remembrance Day, a day for the community to come together and demand that her case not be forgotten.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has released multiple age-progression images over the years, showing what Relisha might look like at 14, at 16, and at 18. On October 29, 2025, she would have turned 20 years old.

To mark what would have been Relisha’s 20th birthday, the Black and Missing Foundation released a powerful new documentary about her disappearance. The Vanishing of Relisha Rudd: A Cold Case Reexamined, a two-part docuseries, premiered in October 2025 with the explicit goal of reigniting public interest in the case and generating new leads.

The documentary features never-before-seen interviews with her stepfather Antonio Wheeler, her grandmother Melissa Young, law enforcement officials, journalists who covered the case, and advocates who have refused to let Relisha be forgotten. It reexamines the systemic failures that allowed Relisha to slip through the cracks and explores why her case—like so many involving missing Black children—received far less media attention than cases involving white children.

“This isn’t just a docuseries, it’s a call to action,” said Derrica and Natalie Wilson, founders of the Black and Missing Foundation. “Relisha deserves to be found. Her story, and the stories of so many others like hers, remind us that visibility is justice. We will never stop searching for Relisha”.

The documentary has sparked renewed conversation about Relisha’s case, with interviews airing on NBC News, local Washington stations, and community forums throughout the D.C. area. Family members have spoken publicly about their continued hope that Relisha will be found.

“She’s DC’s baby,” Derrica Wilson said during a recent interview promoting the documentary. It’s a sentiment that has become a rallying cry for those demanding answers.

The documentary arrives at a critical moment. With each passing year, public memory of Relisha fades. Witnesses forget details. Evidence degrades. Hope dims. But the Wilson sisters and others refuse to let her story disappear into silence.

“Someone out there knows something,” Derrica Wilson insists. “We just need that one person to come forward and help bring answers and justice for Relisha Rudd”.

The Reward Still Stands

More than eleven years after Relisha Rudd walked into that motel room and never came out, the FBI’s reward for information leading to her location and return remains active: $25,000. Tips can be submitted to the FBI at 1-800-CALL-FBI, to the Metropolitan Police Department at 202-727-9099, or to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Relisha’s case remains officially open and unsolved—the only missing person case from 2014 that DC police have not closed. Investigators have conducted numerous searches over the years, including a 2016 search of the National Arboretum and a 2018 search of service tunnels beneath the former DC General shelter. Each search has turned up nothing.

For those who knew and loved Relisha, the waiting is unbearable. “Where’s Relisha?” her grandmother Melissa Young asks, a question that echoes through a decade of silence. “It’s been two years, two long stressful years for grandma,” she said in 2016, her voice weary. Now it has been more than a decade.

Antonio Wheeler still thinks of Relisha in her final moments. “What keeps me up in the past was just her screaming for daddy or screaming for help, period, and nobody was there,” he said, his voice breaking. “Nobody was there”.

But he refuses to give up hope. “I got my hopes. I honestly do,” Wheeler said. “I spoke with my son, and he says he believes she’s still alive, they’re just not looking hard enough. I got hope, but I’m preparing for the worst”.

What Relisha’s Case Teaches Us

Relisha Rudd’s disappearance was not inevitable. It was the result of cascading failures at every level of the systems designed to protect vulnerable children.

It was a failure of the contractor who hired Kahlil Tatum without conducting a proper background check that would have revealed his 17-year criminal history. It was a failure of shelter management, who ignored their own no-fraternization policy and allowed a janitor to form intimate relationships with homeless children. It was a failure of the school system, which accepted forged doctor’s notes for more than a month without verification. It was a failure of Child and Family Services, whose caseworkers didn’t communicate with one another about a family they were all supposed to be monitoring.

And it was a failure of society at large—a failure to see homeless children as worthy of protection, a failure to invest in the supports that struggling families desperately need, a failure to give missing Black children the same urgency and attention afforded to their white counterparts.

“Reimagining life for Relisha Rudd,” an analysis published by the Urban Institute in 2015, explored what her life might have looked like if the systems meant to support her family had actually worked. If her mother had access to affordable housing, mental health services, and job training. If the shelter had been a safe, dignified place with adequate oversight. If Tatum had never been hired, or if someone had intervened when his behavior crossed boundaries.

The answers are clear. Relisha would likely still be here.

A Birthday That Will Never Come

Somewhere in Washington, D.C., in footage that can never be unseen, an 8-year-old girl walks into a hotel room, her small hand in the hand of a man she trusted. The door closes behind them. The hallway is empty. And Relisha Rudd is gone.

If she is still alive, Relisha would be 20 years old now. She would have graduated high school. She might be in college, or starting a career, or building a life of her own. She would have outgrown those pink boots and that purple jacket. She would have laughed and cried and dreamed and loved.

Instead, she exists only in photographs frozen in time. An 8-year-old girl with a radiant smile, forever young, forever missing.

Her stepfather Antonio Wheeler holds onto a fragile hope. “She’s out there,” he said during a recent interview. “I believe that with all my heart. And when she comes home, I’m going to tell her how sorry I am that I wasn’t there to protect her”.

Her grandmother Melissa Young continues to search for answers, attending vigils and speaking to reporters, refusing to let the world forget her granddaughter.

And the advocates at the Black and Missing Foundation continue their work, using Relisha’s story to shine a light on the hundreds of other Black children who vanish each year, whose cases receive little attention, whose families are left to grieve in silence.

“Relisha Rudd is D.C.’s baby,” Derrica Wilson said, standing on a street corner in Northeast Washington, handing out fliers with the missing girl’s face. It’s a sentiment shared by many in the nation’s capital, where Relisha’s story has become a symbol of systemic failure, of lives deemed disposable, of children falling through cracks that should never have existed in the first place.

Her case forced a reckoning. It led to the closure of DC General and the creation of a new shelter system designed to treat families with dignity. It prompted changes in truancy reporting, background check procedures, and child welfare protocols. It sparked conversations about how missing Black children are overlooked and undervalued.

But none of those reforms brought Relisha home.

She Deserves to Be Found

If you have any information about Relisha’s whereabouts, please contact the FBI at 1-800-CALL-FBI, the Metropolitan Police Department at 202-727-9099, or the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST. Someone, somewhere, knows something. A detail that seemed insignificant at the time. A passing comment. A face glimpsed in a crowd.

Relisha Rudd deserves to be found. She deserves justice. She deserves to be more than a cautionary tale, more than a case study in systemic failure, more than a statistic in the ongoing crisis of missing Black children.

She deserves to be remembered as a little girl who loved reading and math, who protected her brothers fiercely, who had a smile that could light up even the darkest shelter. A little girl who trusted the wrong person. A little girl who should still be here.

The surveillance footage plays on a loop in the minds of those who love her. Pink boots. Purple jacket. A small hand in a larger one. A door closing. A hallway empty.

Somewhere, Relisha Rudd is waiting to be found.

And the world is finally paying attention.