The hospital room smelled like antiseptic and new life. It was late November 1978, and the air in rural Wauchula, Florida carried the kind of quiet only small towns know—steady, unassuming, forgiving. Inside Hardee Memorial Hospital, two women lay in separate rooms, their bodies exhausted from labor, their hearts full with a love they had never known before. Neither of them could have imagined that within days, their lives would be tangled in a nightmare so profound, it would take nearly a decade to unravel—and even then, the truth would bring no peace.

Barbara Mays had waited years for this moment. She and her husband Bob had tried for so long to have a child, enduring disappointment after disappointment, praying for the baby they longed to hold. On November 29, 1978, Barbara finally gave birth to a baby girl. But the joy was cut short almost immediately. The infant had a severe heart condition—one so critical that doctors weren’t sure she would survive. The news shattered Barbara. After all the waiting, all the hoping, her baby might not live.

Just three days later, on December 2, 1978, another woman gave birth in the same hospital. Regina Twigg was a school teacher who had grown up in an orphanage, adopted by a family she would later describe as abusive. Regina already had five children at home, and this sixth baby—a healthy, beautiful girl—seemed like another blessing in a life that had known too much hardship. She held her newborn close, unaware that the child in her arms was not the one she had carried for nine months.

Somewhere in the chaos of that small hospital—between the nursery and the recovery rooms, between shifts and paperwork—two babies were switched. The healthy baby born to Regina Twigg was handed to Barbara and Bob Mays, who named her Kimberly. The sick baby born to Barbara Mays was given to Regina and Ernest Twigg, who named her Arlena.

For years, no one knew. The Mays took Kimberly home and loved her fiercely. Barbara’s heart, broken by the belief that her biological child was too ill to survive, found solace in this healthy infant. She poured everything into raising Kimberly, cherishing every moment—until cancer stole her life when Kimberly was just two years old.

Meanwhile, the Twiggs brought Arlena home, a baby with a heart that struggled with every beat. They cared for her, loved her, took her to doctors, watched her fight for every breath. The oldest Twigg child, Irisa Roylance, would later say, “I was very shocked, but she was my sister, so it didn’t matter to me”. For nine years, Arlena lived—a miracle in her own right—but her body couldn’t hold on forever. In 1988, at nine years old, Arlena died.

When Blood Doesn’t Lie

Grief has a way of making people search for answers. After Arlena’s death, Regina and Ernest Twigg began asking questions that had nagged at them for years. Arlena’s blood type had never quite matched theirs. Doctors had explained it away as a rare genetic anomaly, something unusual but not impossible. But now, with Arlena gone, the questions became louder, more insistent.

The Twiggs started digging. They learned that during the week Arlena was born, only two white infants had been delivered at Hardee Memorial Hospital—Arlena and another baby girl. That other baby was Kimberly Mays.

Blood tests were ordered. The results were undeniable: Kimberly Mays was not Bob Mays’ biological daughter. She was the Twiggs’ biological child. And Arlena, the little girl the Twiggs had raised and lost, was biologically Barbara and Bob Mays’ daughter.

Bob Mays had to sit his nine-year-old daughter down and tell her something no child should ever have to hear. Years later, Kimberly would recall the conversation with painful clarity. “He had to sit me down and was like, ‘Look, there’s another family. Their little girl died. Her blood did not match theirs. You were the only other baby born at Hardee Memorial Hospital, and they found you through a detective,’” Kim said. Bob assured her: “‘I just want to let you know that you are my daughter. I love you, no matter what the tests come back, but you have to take a blood test’”.

The story broke in 1988 and exploded across national headlines. A switched-at-birth scandal. A dead child. A family torn apart. America couldn’t look away.

The Question No One Could Answer

How does something like this happen? That was the question everyone demanded an answer to. Bob Mays resisted genetic testing at first, but eventually agreed. The tests confirmed what the Twiggs suspected: the babies had gone home with the wrong parents.

But was it an accident—or something darker?

Regina Twigg believed, with every fiber of her being, that the switch was deliberate. She theorized that hospital staff, sympathetic to Barbara Mays—a woman who had struggled for years to conceive and then gave birth to a baby not expected to survive—made a calculated decision. “They give me the sick baby and give Barbara the healthy baby,” Regina said. She believed Barbara’s parents, desperate for their daughter to have a healthy child, might have been involved. “They just were convinced that baby was going to die,” Regina added.

Regina pointed to Dr. Ernest Palmer, a family practitioner at the hospital, claiming he ordered nurses or nurses’ aides to switch the babies’ ID bands. Palmer has since died, taking any potential answers with him.

Bob Mays denied any knowledge of the switch. His attorney said he had passed a lie detector test “with flying colors”. But Regina Twigg’s suspicions persisted. She couldn’t shake the feeling that someone had made a choice—that her healthy baby had been deliberately taken from her and given to another family.

In 1993, a nurse’s aide from the hospital came forward with a stunning claim: a doctor had asked her to switch the ID bracelets. The revelation seemed to validate Regina’s theory, but inconsistencies in the aide’s story raised new questions. The truth, if it existed, remained elusive—buried somewhere in the past, in memories that had faded, in records that couldn’t speak.

Both families sued the hospital. The legal battles were long and draining, but eventually, they were awarded multimillion-dollar settlements totaling $13.6 million. The hospital never admitted fault.

Money, though, couldn’t undo what had been done. It couldn’t bring Arlena back. It couldn’t erase the years Kimberly had spent with the Mays or the years the Twiggs had spent loving a child who wasn’t biologically theirs. It couldn’t heal the gaping wounds left by a mistake—or a crime—that had shaped so many lives.

A Custody Battle That Broke a Child

Regina Twigg, having lost one daughter, wanted desperately to know the other. She pushed for the right to see Kimberly, to develop a relationship with the girl who was, by biology, her daughter. Bob Mays resisted. Kimberly was his daughter, the child he had raised, the only family he had left after Barbara’s death. He wasn’t going to lose her too.

The custody battle that followed was brutal. It played out in courtrooms and on television, with lawyers arguing over blood and love, biology and bonds. Kimberly, caught in the middle, became a pawn in a fight she never asked to be part of.

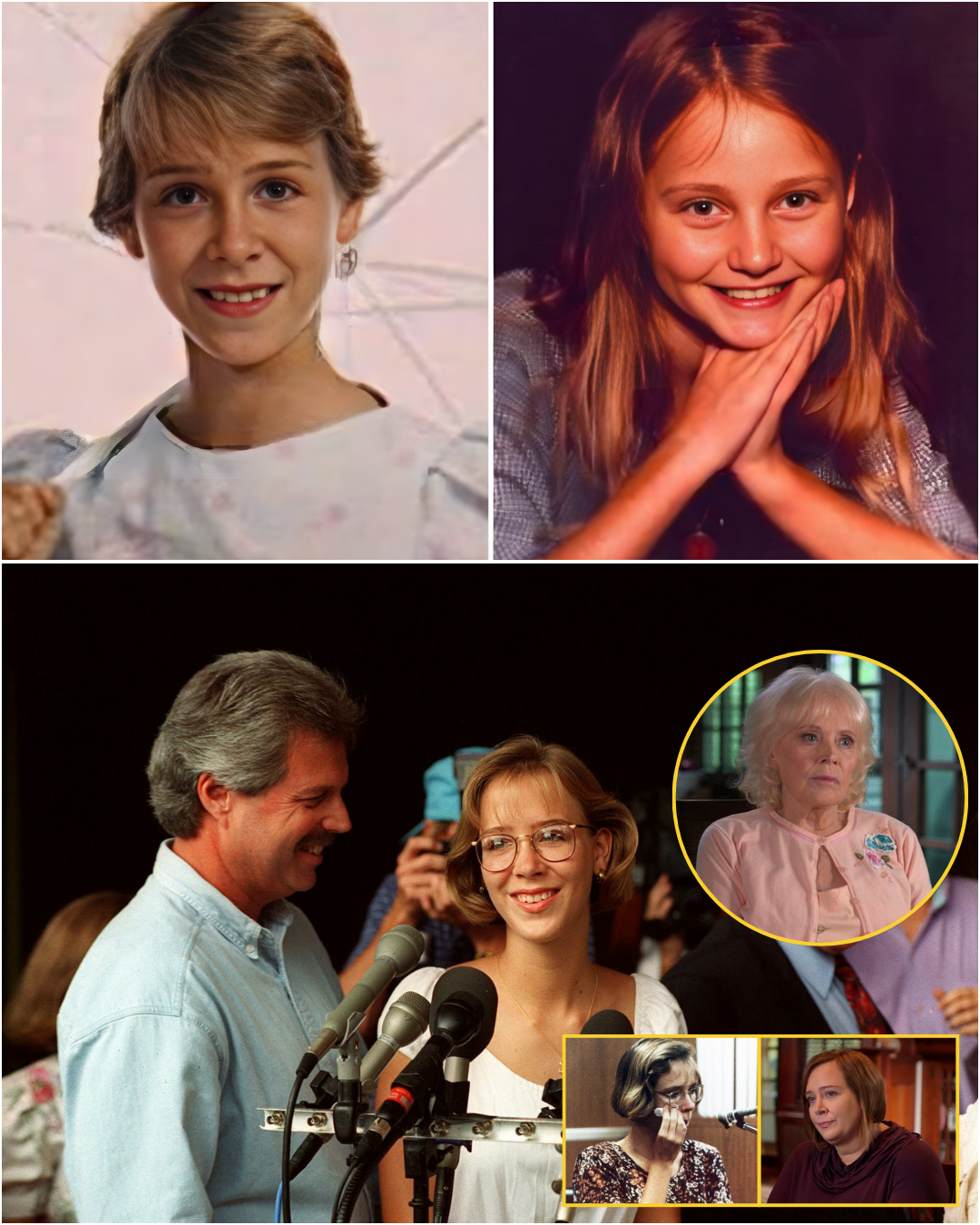

In 1993, when Kimberly was a teenager, she made a decision that shocked the nation: she went to court to legally “divorce” her biological parents, the Twiggs. She testified that she never wanted to see them again. A judge in Sarasota, Florida ruled in her favor, allowing her to stay with Bob Mays, the man who had raised her.

The ruling ended seven years of legal battles, but it didn’t end the pain. Kimberly later admitted she “was never close” with Regina Twigg. Looking back decades later, when asked who she considers her mother now, Kimberly said, “I really don’t feel I have one”.

“I try not to dwell on [the past]. I try not to have anger. I try to move forward the best I can,” Kimberly, now in her 40s, told ABC’s “20/20”.

But moving forward doesn’t mean forgetting. The scars remain—etched into every person touched by the switch, a reminder that some mistakes can never truly be undone.

Hundreds of Miles Away, Another Switch

While the Mays-Twigg case dominated headlines, another hospital, hundreds of miles north, was about to face its own nightmare.

It was July 1995 in Charlottesville, Virginia. The University of Virginia Medical Center, a respected institution known for its care and precision, delivered two baby girls within days of each other. Paula Johnson gave birth to a healthy baby girl on June 29, 1995. Around the same time, Whitney Rogers and her fiancé Kevin Chittum welcomed their daughter.

Both families took their babies home, unaware that the infants had been switched in the hospital nursery. Paula Johnson named her baby Callie. Whitney Rogers and Kevin Chittum named theirs Rebecca Grace.

For three years, life went on. Paula raised Callie. Whitney and Kevin raised Rebecca. Then, on July 4, 1998, tragedy struck: Whitney Rogers and Kevin Chittum were killed in a horrific car crash, along with four other people. Rebecca, just three years old, went to live with her grandparents, Larry and Rosa Chittum.

The grief was unimaginable. But in the midst of mourning, another revelation was about to shatter what remained of their world.

Paula Johnson, who was not married, had been pursuing child support from the man she believed to be Callie’s father. As part of the legal process, genetic testing was ordered. The results came back, and they made no sense: the man was not Callie’s biological father. More shocking: Paula Johnson was not Callie’s biological mother.

Confused and desperate for answers, Paula’s attorney contacted the University of Virginia Medical Center on July 16, 1998. Hospital officials reviewed records and identified another infant born around the same time—Rebecca Grace Chittum. Blood tests confirmed the unthinkable: the babies had been switched.

Paula Johnson’s biological daughter was Rebecca, the little girl being raised by the Chittums. And Callie, the child Paula had been raising, was the biological daughter of Whitney Rogers and Kevin Chittum—parents who had died never knowing their real daughter had been taken from them.

A Mystery With No Clear Answer

The University of Virginia Medical Center was baffled. How could this have happened? Hospital officials insisted they had taken proper precautions. Chief of Staff Thomas Massaro reviewed the case and concluded that an accidental misidentification of infants was unlikely. Believing the switch was a criminal act, the hospital requested an investigation by Virginia State Police.

The investigation lasted four months. Detectives pored over medical records, interviewed hospital staff, and examined family videotapes and photographs. What they found was troubling: Rebecca and Callie had problems with their ID bands before they were discharged.

“In one case, one band is missing and the other is noticeably loose. In the other case, neither identifying band is visible on the child,” the investigative report stated. Cynthia Johnson, an attorney for the families, said investigators told them that ID bands fall off, “and either they are not replaced or they are kept inside the bassinet and, in some cases, actually taped inside the bassinet”.

Investigators determined the switch occurred in the nursery between 6 and 8:30 a.m. on July 1, 1995. At least eight hospital workers were caring for as many as 15 infants during that time.

But despite the investigation, no one could say exactly what happened. “The precise events which occurred are unknown at this time and may never be known,” the police report concluded. “However, there is currently no evidence from which to conclude that the switch of these children was an intentional act”.

Paula Johnson believed the truth was simpler—and more frustrating. “It’s something that is so routinely done that they just honestly don’t remember doing this to these kids,” she said. Too much time had passed. Nurses couldn’t recall specifics. The bands had come loose or gone missing, and in the chaos of a busy nursery, two babies had been sent home with the wrong families.

“That’s a missing part of my life, a missing part of all of our lives,” Paula Johnson said.

Two Little Girls, Two Impossible Choices

The custody battles that followed the Virginia discovery were nothing short of agonizing. On one side: Paula Johnson, a single mother who had raised Callie for three years, who had fed her, bathed her, comforted her when she cried, celebrated every milestone. On the other side: the Chittums—Larry and Rosa, Kevin’s parents, and Linda Rogers, Whitney’s mother—who had lost their children in a devastating crash and were now raising Rebecca, the only piece of their son and daughter they had left.

Except Rebecca wasn’t their biological granddaughter. And Callie, the girl Paula was raising, wasn’t her biological daughter.

The question before the courts was brutal in its simplicity: What do you do when biology and love are at war? When the child you’ve raised isn’t yours by blood, but is yours in every other way that matters? When the child who shares your DNA is being raised by strangers?

Paula Johnson wanted custody of Rebecca, her biological daughter. But Rebecca had just lost her parents—the only parents she had ever known. She was being cared for by her grandparents, the Chittums, who loved her and had already suffered an unimaginable loss. To take Rebecca away from them would be to tear her from the only family she had left.

In November 1999, Juvenile Court Judge John Curry made his ruling. Paula Johnson would not be awarded custody of Rebecca. The little girl would remain with her grandparents, Larry and Rosa Chittum. Johnson was granted visitation rights—she could be part of Rebecca’s life, but she could not take her home.

“Things are going to be OK,” a sobbing Paula Johnson said after the order was handed down. “This is all I’ve ever asked for, to be a part of this child’s life and know that she’s OK”.

Psychologist Nadia Kuley, who had spent more than five hours evaluating Rebecca over two months, testified that the girl was coping well with the loss of her parents but could suffer severe emotional distress if she were separated from her grandparents. Rebecca remained unaware that Kevin Chittum and Whitney Rogers—the couple she knew as Mom and Dad—were not her biological parents.

Kuley noted that the relationship between Johnson and the Chittums had started as positive but quickly soured. “Then they developed anxiety and fear. They said they had heard that Johnson had threatened to kidnap Rebecca,” Kuley testified.

After Judge Curry handed down his order, Johnson and Linda Rogers—the maternal grandmother of Callie, the girl Johnson was raising—hugged and cried. “I told her that I was sorry that all this time had gone by, but I was scared of her. I knew she could take away from me something that I cherished so much,” Rogers said. Rogers retained shared custody of Rebecca.

Meanwhile, Johnson kept custody of Callie, the girl she had been raising—the biological daughter of Kevin Chittum and Whitney Rogers. A judge ruled that Johnson would retain custody “because nobody else has come forward,” though the dead couple’s parents could petition for custody in the future.

It was a Solomon’s choice with no good answers. Two families, each raising a child who wasn’t biologically theirs, each loving a child they couldn’t bear to lose. The switch had created bonds that couldn’t be broken without causing more pain—so the courts chose to let those bonds remain, imperfect and complicated as they were.

The Scars That Never Heal

Decades have passed since these cases first made headlines. The lawsuits have been settled. The custody battles have ended. But for the people at the center of these stories, the pain has never fully gone away.

Kimberly Mays is now in her 40s, a mother herself. When she sat down with ABC’s “20/20” in 2019, more than 30 years after learning she had been switched at birth, she reflected on a life shaped by forces beyond her control.

After winning the right to “divorce” her biological parents in 1993, Kimberly shocked everyone by running away from Bob Mays just months later and moving in with the Twiggs. “I wasn’t prepared for, like, life,” she told “20/20”. The teenage years were turbulent. She struggled to find her place, caught between two families, neither of which felt entirely like home.

Eventually, she terminated her relationship with the Twiggs as well. Bob Mays, the man who raised her, died in 2012. Kimberly had not been in touch with him for some time before his death.

Today, Kimberly is estranged from all her Twigg family members, including Regina. Her relationship with Darlena Mays, Bob’s second wife and Kimberly’s stepmother, remains strained, though when they are in contact, Kimberly says Darlena has been very good to her.

“I was never close with Regina,” Kimberly admitted. “But I do know she has a good heart. She’s been through a lot”.

When asked who she considers her mother now, Kimberly’s answer is heartbreaking: “I really don’t feel I have one”.

“I feel bad for both sides, [the] Twiggs and everyone involved,” she said. “[Arlena] passed away and then they poured everything into finding me, so they went through a lot”.

“I try not to dwell on [the past]. I try not to have anger. I try to move forward the best I can,” Kimberly said.

But some things can’t be left in the past. The trauma of being switched at birth, of becoming the center of a national custody battle, of losing the only parent you knew while being told another family has a claim on you—those experiences leave marks that don’t fade.

Regina Twigg, now divorced from Ernest and remarried, has pursued her passion for music as a singer and songwriter. She has tried, over the years, to have a relationship with Kimberly, but it has been difficult.

“I would say to Kim that I hope life will be positive for her and good for her. I will always love her,” Regina said. “In spite of the pain of what happened in the past, like it is said, ‘You put one foot ahead of the other and just carry on’”.

But carrying on doesn’t mean the pain is gone. It just means you’ve learned to live with it.

The Unanswered Questions

To this day, no one knows for certain how or why these switches happened. Were they accidents—tragic, preventable mistakes made in the chaos of busy hospital nurseries? Or were they something darker, deliberate acts by someone who believed they were doing the right thing?

In the Florida case, Regina Twigg has never wavered in her belief that the switch was intentional, orchestrated by hospital staff who felt sympathy for Barbara Mays. A nurse’s aide came forward in 1993 claiming a doctor asked her to switch the ID bracelets—but inconsistencies in her story left more questions than answers. Dr. Palmer, the man Regina believes ordered the switch, died without ever confirming or denying the accusation.

In the Virginia case, investigators found troubling evidence of loose or missing ID bands, but they could not prove intent. “The precise events which occurred are unknown at this time and may never be known,” the police report concluded. “However, there is currently no evidence from which to conclude that the switch of these children was an intentional act”.

Paula Johnson believes the truth is simpler: it was human error, compounded by time and faded memories. “It’s something that is so routinely done that they just honestly don’t remember doing this to these kids,” she said.

Both hospitals were sued. Both paid multimillion-dollar settlements. Neither admitted fault.

Money can’t bring back lost years. It can’t undo the trauma. It can’t answer the questions that haunt everyone involved: What if the switch had never happened? What if Arlena had lived? What if Kevin and Whitney had never gotten in that car on July 4, 1998? What if?

A Pain That Echoes Across Generations

The ripple effects of these switches extend far beyond the two girls at the center of each story. There are siblings who grew up with someone they thought was their sister, only to learn she wasn’t related to them by blood. There are grandparents who lost grandchildren they never got to know. There are parents who died never knowing the truth.

Irisa Roylance, one of the Twigg children who grew up with Arlena, remembers the shock of learning the truth. “I was very shocked, but she was my sister, so it didn’t matter to me,” she said. For nine years, Arlena was their sister—she lived with them, played with them, struggled for breath with them. Blood didn’t change that.

But it did change everything else. The Twiggs poured all their grief into finding Kimberly, the biological daughter they had never known. When they finally did, she didn’t want them. She couldn’t. She had a father—Bob Mays—and no amount of genetics could replace the bond they had built.

The Twigg siblings watched as their parents fought for a girl who felt like a stranger, while mourning the sister they had lost. The family was fractured in ways that could never be fully repaired.

In Virginia, the Rogers and Chittum families faced their own impossible grief. They had lost Whitney and Kevin—vibrant young parents taken too soon. And then, just over a year later, they learned that Rebecca, the little girl they were raising in their children’s memory, wasn’t their biological granddaughter. The child who carried Whitney’s smile, Kevin’s eyes—she wasn’t theirs by blood.

And somewhere else, Paula Johnson was raising Callie—a girl she loved with everything she had, even though Callie was the biological daughter of the couple who had died. Paula couldn’t have her biological daughter, Rebecca, but she could be part of her life, visit her, watch her grow from a distance.

It was a compromise born of necessity, not justice. Everyone lost something. No one got what they wanted.

When Systems Fail

These cases exposed the fragility of the systems meant to protect us. Hospitals are supposed to be places of safety, where new life enters the world under careful watch. But in Wauchula, Florida in 1978, and in Charlottesville, Virginia in 1995, those systems failed.

ID bands fell off or were never properly secured. Nurses worked long shifts, caring for too many babies at once. Records were incomplete or unclear. And in the chaos—whether by accident or design—two babies went home with the wrong families.

After the Virginia case, the University of Virginia Medical Center reviewed its procedures. Chief of Staff Thomas Massaro concluded that an accidental misidentification was unlikely—but he couldn’t prove it was intentional either. The truth lived somewhere in the gray space between error and intent, and it was maddeningly out of reach.

Hospitals implemented new protocols. ID bands became more secure. Procedures for identifying newborns became stricter. But no system is foolproof. As long as humans are involved, mistakes will happen.

The question is: how do we live with those mistakes when they happen? How do families rebuild when the foundation of their lives—the belief that they know who their children are—has been shattered?

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

In the years since these cases, switched-at-birth stories have taken on a life of their own in American culture. They’ve become the subject of made-for-TV movies, news specials, true crime documentaries. People are fascinated by the idea—the horror and the intrigue of it. What would you do if you found out the child you raised wasn’t biologically yours? What if you discovered your real parents were strangers?

But for the people who lived it, these aren’t stories. They’re scars.

Kimberly Mays became a household name in the 1990s, her face on television screens across America as her custody battle played out in real time. People had opinions—loud, certain opinions—about what should happen to her, where she belonged, who her “real” family was. But Kimberly was just a kid, caught in the middle of something she didn’t choose and couldn’t control.

“You don’t realize the impact of everything,” she said decades later. “I wish I could turn back the hands of time on a lot of things”.

The Virginia girls, Rebecca and Callie, were luckier in one sense: their story didn’t become a media circus in the same way. The families worked out private arrangements, kept the girls’ lives as stable as they could. But the trauma was still there, lurking beneath the surface, shaping their childhoods in ways that wouldn’t be fully understood until they were older.

Psychologists who study identity and attachment warn that children in these situations face unique challenges. They may feel detached from the family they grew up in, yet rejected by their biological family. They struggle with questions of identity: Who am I? Where do I belong? Which parents are my “real” parents?

For some, like Kimberly, the answer is that there is no answer. “I really don’t feel I have one,” she said when asked who she considers her mother now. It’s a profound loss—not just of a relationship, but of the very idea of “mother,” a concept most people take for granted.

The Legacy of Loss

Today, both of these cases stand as cautionary tales—reminders of what can go wrong when systems fail, when humans make mistakes, when the unthinkable happens.

They’re also stories of resilience. Kimberly Mays, despite everything, has tried to move forward, to build a life for herself and her own children. Paula Johnson fought for the right to be in her biological daughter’s life and won, even if it wasn’t the outcome she dreamed of. The Chittums and Rogers family raised Rebecca with love, giving her stability after the unimaginable loss of her parents.

But the pain remains. It lives in the memories, in the what-ifs, in the relationships that were never given a chance to develop naturally.

Regina Twigg lost Arlena, the daughter she raised for nine years. Then she lost Kimberly, the daughter she gave birth to but never got to mother. She carries both losses with her every day.

Bob Mays raised Kimberly as his own, loved her fiercely, protected her from the world—but in the end, she pulled away from him too. He died estranged from the daughter he fought so hard to keep.

Paula Johnson got to be part of Rebecca’s life, but only as a visitor, watching from the sidelines as her biological daughter grew up in another family.

These are not stories with happy endings. They’re stories of survival, of people doing the best they could with an impossible situation.

The Questions That Linger

Even now, decades later, the questions remain. Was the Florida switch deliberate? Did someone at Hardee Memorial Hospital make a calculated decision to give the Mays a healthy baby? Or was it simply a tragic mistake, a moment of confusion that changed lives forever?

In Virginia, were the loose ID bands a sign of negligence, or just bad luck? Could the switch have been prevented? Should someone have been held accountable?

The legal system provided partial answers—settlements were paid, custody arrangements were made. But the deeper questions—the moral, emotional, existential questions—those remain unanswered.

What does it mean to be a parent? Is it biology, or is it the years spent raising a child, the sleepless nights, the scraped knees bandaged, the stories read at bedtime?

What does it mean to be a family? Is it blood, or is it the bonds forged through shared experiences, through love given and received?

For Kimberly Mays, the answer is complicated. She was raised by Bob Mays, but Barbara Mays—the woman who would have been her mother if the switch hadn’t happened—died when Kimberly was two. She never knew Barbara. And she never felt close to Regina, her biological mother. So where does that leave her?

“I try not to dwell on [the past]. I try not to have anger. I try to move forward the best I can,” she said.

It’s all anyone can do. Move forward. Carry on. Put one foot ahead of the other, as Regina said.

But the past doesn’t disappear. It follows, a shadow that grows longer with each passing year.

A Pain That Doesn’t End

In 2019, when Kimberly sat down for that interview with “20/20,” she was asked if she thought she would ever get over it. Her answer, given when she was just a teenager fighting for the right to stay with Bob Mays, still holds true decades later: “No. Never”.

Some wounds don’t heal. They just become part of who you are.

Regina Twigg still loves the daughter she gave birth to, even though that daughter feels like a stranger. Paula Johnson still aches for the years she lost with Rebecca, years she can never get back. The Chittums and Rogers families still grieve for Whitney and Kevin, a grief made more complicated by the discovery that the child they’re raising isn’t their biological granddaughter.

These families carry their losses with them, every day. They’ve learned to live with the pain, to build lives around the holes that can never be filled.

And somewhere in America, there are two women—Kimberly Mays and Rebecca Chittum—who grew up knowing they were switched at birth, that the families they belonged to by blood were not the families who raised them. They carry that knowledge with them, a weight that never gets lighter, only more familiar.

Their stories are reminders that some mistakes have consequences that last a lifetime. That love and biology are not always the same thing. That family is both simpler and more complicated than we like to believe.

And that sometimes, no matter how hard we fight, how much we love, how desperately we try—there are no good answers. Only choices, all of them painful, all of them imperfect.

The babies switched at birth in 1978 and 1995 are women now, living their lives, raising their own children. They’ve survived something most people can’t imagine. But survival isn’t the same as healing.

The wounds remain. The questions linger. And the pain—quiet, persistent, undeniable—never truly goes away.

It just becomes part of the story they tell themselves about who they are, where they came from, and what they lost before they were old enough to understand what loss meant.