The guard’s keys rattled in the lock one final time. Damien Echols stepped into sunlight he hadn’t felt on his face since he was eighteen years old. He was thirty-six now. Half his life had been spent waiting to die for a crime he swore he never committed.

But as cameras flashed and reporters shouted questions, no one from the state of Arkansas uttered the word he’d been waiting eighteen years to hear: innocent.

Instead, they made him say he was guilty.

This is the story of how three teenagers became the most controversial convicted murderers in American history—and how justice, when it finally came, looked nothing like freedom.

The Day the Boys Didn’t Come Home

May 5, 1993. West Memphis, Arkansas. The kind of small town where mothers still let their eight-year-old sons ride bikes to the woods after school.

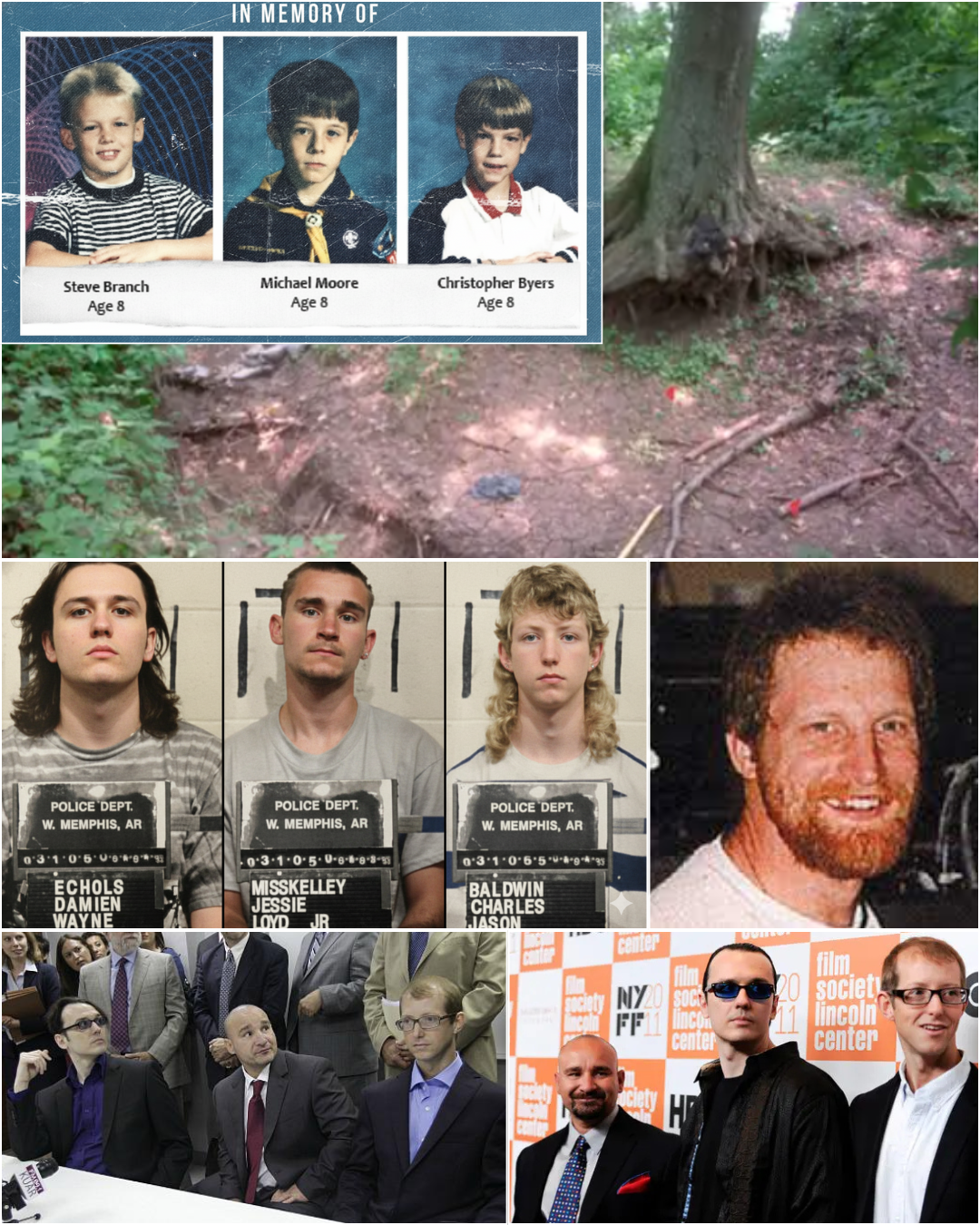

Stevie Branch left home around 3:30 that afternoon. His best friends, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers, pedaled alongside him toward Robin Hood Hills—a tangled stretch of forest where neighborhood kids built forts and pretended to be outlaws. By six o’clock, someone spotted all three boys riding their bikes on North Fourteenth Street, heading toward the woods.

They were never seen alive again.

At eight-ten that evening, John Mark Byers called the West Memphis police. His stepson Christopher hadn’t come home for dinner. Ten minutes later, Dana Moore and Pamela Hobbs made similar calls about their sons. Panic spread fast in a town of twenty-eight thousand. By nine-thirty, search parties were combing Robin Hood Hills with flashlights, calling out names that would soon be printed on missing-child flyers.

The next afternoon, a searcher spotted something pale floating in a drainage ditch. At 1:45 p.m. on May 6, police pulled Michael Moore’s naked body from the muddy water. Within two hours, they found Stevie and Christopher in the same ditch, their hands tied behind their backs with their own shoelaces. All three had been beaten. One showed injuries so severe the medical examiner would later testify the child had been mutilated.

The coroner estimated the boys died sometime between one and five that morning.

West Memphis had never seen anything like this. Parents locked their doors. Churches held candlelight vigils. And the police—desperately searching for answers—began looking for someone dark enough, strange enough, evil enough to have done this to three innocent children.

They found Damien Echols.

The Boy Who Wore Black

Seventeen-year-old Damien didn’t fit in West Memphis, and he didn’t try to. He dressed in black. He read books about Wicca and the occult. He wrote poetry about death. In a conservative Arkansas town where most teenagers wore boots and baseball caps, Damien stood out like a stain.

He also had a history. The previous year, he’d spent time in a psychiatric hospital in Little Rock after incidents at a juvenile detention center—including one report that he’d sucked blood from another detainee’s wound and threatened to kill his father. Mental health records showed he’d been treated for major depression. Local authorities knew he had an interest in witchcraft. Some suspected him of Satanism.

When three boys turned up dead in what looked like a ritualistic killing, police immediately thought of Damien.

On May 7—just one day after the bodies were found—Detective Steve Jones questioned Damien about the murders. Three days later, police brought him back to the station for a polygraph test. According to the detective’s notes, the examiner reported that Damien “had been untruthful, and according to the polygraph, was involved in the murders”.

But there was a problem. Police had no physical evidence linking Damien to the crime scene. No fingerprints. No DNA. No witnesses who saw him anywhere near Robin Hood Hills that night. His mother told police he’d been home with her the entire evening, talking on the phone to friends in Memphis.

They needed more than a failed polygraph. They needed a confession.

So they turned to Damien’s acquaintance: a borderline intellectually disabled teenager named Jessie Misskelley Jr.

The Confession That Changed Everything

Jessie Misskelley was seventeen years old with an IQ measured between 67 and 75—low enough to be considered intellectually disabled. He lived in a trailer park near Damien and knew him only casually. He barely knew Jason Baldwin, Damien’s best friend, at all.

On June 3, 1993, police picked Jessie up for questioning. They told him there was a thirty-five-thousand-dollar reward for information leading to convictions in the case. Then they interrogated him for twelve hours. No lawyer. No parent in the room. Just Jessie, two detectives, and the promise of money.

Detective Durham would later tell another officer that Jessie was “lying his ass off”. The interrogation grew harsher. The questions more leading. And slowly, after hours of pressure, Jessie began to tell police what they wanted to hear: that he, Damien, and Jason had murdered the three boys.

But his story didn’t match the facts.

Jessie said the murders happened during the day. They actually occurred at night. He said they tied the boys up with rope. The killer had used shoelaces. He said they raped the victims. The medical examiner found no evidence of sexual assault. He said one boy was cut with a knife in ways that didn’t match the autopsy reports.

Police worked with Jessie to “correct” his story—feeding him details until his confession aligned with what they knew about the crime. After hours of interrogation, they finally turned on a tape recorder and captured Jessie’s “confession”.

Jessie recanted his statement immediately upon being released to his family, stating that police forced the story from him through threats and the lure of reward money. But it was too late.

That night, police arrested all three teenagers. Damien Echols. Jason Baldwin. Jessie Misskelley. Each was charged with three counts of capital murder.

At a press conference the next morning, Chief Inspector Gary Gitchell told reporters he was confident about the case. On a scale of one to ten, he said his confidence level was “eleven”.

The Trials Built on Fear

The trials began in early 1994. Jessie was tried separately from Damien and Jason. His defense attorneys argued that his confession had been coerced—that a mentally disabled teenager had been manipulated into admitting to a crime he didn’t commit. But Judge David Burnett ruled the confession admissible.

On February 5, 1994, a jury found Jessie Misskelley guilty of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison plus forty years.

Two weeks later, Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin went on trial together. Prosecutors built their case on a disturbing narrative: that the three teenagers had killed the boys as part of a Satanic ritual. They pointed to Damien’s interest in the occult. They called witnesses who testified about his strange behavior. They introduced Jessie’s confession—even though Jessie refused to testify and his statement implicated himself as much as the others.

But they still had no physical evidence. No DNA. No forensic proof. Just suspicion, circumstantial details, and the word of a confused teenager with an IQ of seventy-two.

It was enough.

On March 18, 1994, the jury found both defendants guilty of capital murder. Damien Echols, eighteen years old, was sentenced to death by lethal injection. Jason Baldwin, sixteen, was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

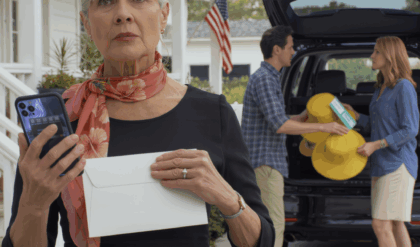

The courtroom erupted. Families of the victims wept with relief. Damien’s mother collapsed. And in the back of the room, documentary filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky kept their cameras rolling—capturing footage that would eventually spark a movement.

When Cameras Exposed the Truth

In 1996, HBO released Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills—a documentary that examined the West Memphis Three case in excruciating detail. The film raised disturbing questions. Why was there no physical evidence? How reliable was a confession from a teenager with intellectual disabilities? Had the Satanic Panic of the early 1990s influenced the jury’s verdict?

Viewers were shocked by what they saw. The interrogation tactics. The lack of forensic proof. The apparent rush to judgment. The documentary didn’t claim the three were innocent—but it suggested the possibility that they might be.

Public opinion began to shift. Celebrities took notice. Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder from Pearl Jam, and filmmaker Peter Jackson became vocal supporters of the West Memphis Three. Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks wore a t-shirt with Damien’s face on it during concerts. Henry Rollins organized benefit concerts and raised over one hundred thousand dollars for new DNA testing.

Metallica—the same band whose music had been used as “evidence” of Satanic influence at trial—allowed the filmmakers to use their songs in the documentary for free.

Two sequels followed: Paradise Lost 2: Revelations in 2000 and Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory in 2011. Each film documented new developments in the case, new DNA evidence, new theories about alternative suspects. By the time the third film premiered, public opinion had shifted dramatically. Polls showed that a majority of Americans believed the West Memphis Three were innocent.

Meanwhile, Damien sat on death row. Jason and Jessie languished in separate prisons. And the families of the murdered boys remained divided—some believing justice had been served, others growing uncertain.

Then, in 2007, everything changed.

The DNA That Pointed Somewhere Else

After years of legal battles, the defense team finally secured permission to conduct advanced DNA testing on evidence from the crime scene. The results, released in July 2007, were stunning.

None of the genetic material found on the victims’ bodies matched Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, or Jessie Misskelley. Not a single hair. Not a drop of blood. Not a trace of skin cells. A joint report issued by both the state and the defense team acknowledged: “Although most of the genetic material recovered from the scene was attributable to the victims of the offenses, some of it cannot be attributed to either the victims or the defendants”.

In other words, someone else’s DNA was at the crime scene—but it wasn’t the three men sitting in prison.

The defense pushed further. They found a hair—a single strand—that had been tied into the ligature binding one of the boys. Advanced mitochondrial DNA testing showed it was consistent with Terry Hobbs, the stepfather of victim Stevie Branch.

Terry Hobbs had never been considered a serious suspect. But now, new witnesses came forward. Three people said they saw Terry with the three boys around 6:30 p.m. on May 5—right around the time they disappeared. Terry had sworn under oath that he never saw the boys that day.

Stevie’s mother, Pam Hobbs—who had divorced Terry years earlier—made a shocking statement. She said she now believed the West Memphis Three were innocent. She revealed that after Stevie’s death, she’d found her son’s pocket knife in Terry’s nightstand drawer—a knife she thought had been lost with Stevie’s body. She also said Terry had washed their bed sheets and curtains at a strange time around the date of the murders.

The case was unraveling. But Damien, Jason, and Jessie remained behind bars.

Eighteen Years in Hell

Damien Echols was eighteen years old when he arrived on death row in Arkansas. He would spend the next eighteen years there—half his life—in a six-by-nine-foot cell designed for men waiting to die.

He was in solitary confinement for most of those years. Twenty-three hours a day alone in a cell, with one hour of “recreation” in a concrete cage barely larger than his living space. He couldn’t see the sky. He couldn’t feel rain. He lost track of what year it was, what month, sometimes even what day.

He watched men around him deteriorate. Some screamed through the night. Some stopped speaking altogether. Some attempted suicide—and a few succeeded. Damien clung to routines to keep himself sane: meditation, yoga, writing letters to his wife Lorri Davis, who he married in a prison ceremony in 1999.

Lorri had seen the Paradise Lost documentary and become convinced of his innocence. She began writing to him, visiting him, advocating for him. Eventually, she fell in love with him—and married a man who was scheduled to die.

Johnny Depp became another lifeline. The actor had seen the documentary and was horrified by what he believed was a wrongful conviction. He began corresponding with Damien, sending him books, money for the commissary, and eventually helping fund legal appeals.

But letters and celebrity support couldn’t change the fact that Arkansas had scheduled his execution. Three times, Damien came within weeks of being strapped to a gurney and injected with a cocktail of drugs designed to stop his heart. Three times, last-minute legal appeals postponed the date.

And then, in 2007, the DNA results came back.

None of it matched him.

The Devil’s Bargain

In 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered a new evidentiary hearing based on the DNA results and potential juror misconduct. For the first time in sixteen years, there was real hope that the West Memphis Three might get a new trial.

But prosecutors had a different plan.

They offered a deal: an Alford plea. It’s a rare legal mechanism that allows defendants to maintain their innocence while pleading guilty—acknowledging that the state has enough evidence to convict them if the case goes back to trial.

For Damien, Jason, and Jessie, it was an impossible choice. Accept the deal, and they’d walk free immediately—but with felony convictions on their records for the rest of their lives. Reject it, and they’d face another trial—with the possibility of spending more years in prison, or in Damien’s case, execution.

Jason Baldwin refused at first. He’d spent seventeen years insisting he was innocent. The idea of pleading guilty—even under an Alford plea—felt like a betrayal of everything he’d fought for. But Damien was still on death row. If they didn’t take the deal, Damien might die.

Jason relented.

On August 19, 2011, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley stood before Judge David Laser and entered Alford pleas to three counts of first-degree murder. The judge sentenced them to time served—eighteen years—and released them with ten-year suspended sentences.

They walked out of the courtroom as free men. But their criminal records still listed them as convicted murderers.

No one said they were innocent. No one apologized. No one admitted a mistake had been made.

Outside the courthouse, Damien stood on the steps, blinking in the Arkansas sunlight, trying to process what had just happened.

He was free. But he wasn’t exonerated.

“It’s not victory,” he told reporters. “It’s a compromise”.

Building Lives From Ruins

Damien Echols walked out of prison at thirty-seven years old. He’d spent eighteen years on death row—half his life. He didn’t know how to use a smartphone. He’d never seen a Marvel movie. The world moved on without him, and now he had to catch up.

He and Lorri moved to New York. He wrote his memoir, Life After Death, which became a bestseller. Johnny Depp wrote the foreword and compared Damien’s prose to Dostoyevsky. He became an artist, a writer, a public speaker. He practices ceremonial magic—spelled “magick” in the tradition of Aleister Crowley, his favorite author.

Jason Baldwin, meanwhile, stayed out of the spotlight. He tried to build a quiet life, away from cameras and documentaries and endless questions about whether he really killed those boys. He’d lost eighteen years. He couldn’t get them back. The best he could do was move forward.

Jessie Misskelley returned to Arkansas and enrolled in community college to train as an auto mechanic. He got engaged to his high school girlfriend. He doesn’t give interviews. He doesn’t want to talk about what happened. He just wants to be left alone.

But none of them can escape the fact that they’re still convicted murderers. The Alford plea gave them freedom—but it didn’t give them innocence.

They can’t vote. They can’t own guns. Every job application, every background check, every time they have to fill out government paperwork, they have to check the box that says “convicted murderer”.

And they can never sue the state of Arkansas for wrongful imprisonment.

The Evidence That Vanished

In 2024, Damien’s legal team made a troubling discovery.

When they requested permission to conduct advanced DNA testing on evidence from the crime scene—testing that hadn’t existed in 1993—they were told that much of the evidence had been lost or destroyed.

Boxes of materials that should have been preserved under Arkansas law were missing. Items that could have definitively proven innocence or guilt were gone. Some had been destroyed. Others simply vanished. No one could—or would—explain what happened.

“We are deeply concerned about the sequence of events,” said Damien’s attorney, Patrick Benca. “Was the evidence lost after we requested advanced DNA testing? What evidence is left? Where does that evidence reside now?”

It’s a chilling question. If the West Memphis Three are innocent, the missing evidence might have exonerated them completely. If they’re guilty, that same evidence might have confirmed it beyond doubt. But now, no one will ever know.

The West Memphis Police Department has not commented on the missing evidence.

In August 2025, after years of legal battles, Judge Tonya Alexander finally granted permission for new DNA testing on the remaining evidence. Advanced techniques—including genetic genealogy, the same method used to identify the Golden State Killer—will be applied to biological samples from the crime scene.

One key piece of evidence: the shoelaces used to bind the boys. Forensic experts believe that if any DNA survived three decades, it would be in the knots—protected from water contamination and degradation.

“If there’s still DNA on those ligatures, we’ll find it,” said Jared Bradley, president of M-Vac Systems, the company handling the testing.

The results could finally answer the question that’s haunted this case for thirty-two years: Who killed Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers?

But as of now, the testing is ongoing. And no one knows what it will reveal.

The Families Who Can’t Agree

Terry Hobbs has never been charged with any crime. He has consistently denied any involvement in the murders of the three boys—including his stepson, Stevie Branch.

But the DNA evidence is difficult to ignore. A hair tied into the ligature binding one of the victims is consistent with Terry’s mitochondrial DNA profile. Three witnesses say they saw him with the boys shortly before they disappeared—testimony that contradicts his sworn statement that he never saw them that day.

Pam Hobbs, Stevie’s mother, has publicly stated that she believes the West Memphis Three are innocent and that her ex-husband should be investigated. She’s pointed to Terry’s strange behavior after Stevie’s death—including washing their bed linens and curtains at an unusual time and the discovery of Stevie’s pocket knife in Terry’s nightstand, a knife she thought had been lost with Stevie’s body.

But not all the families agree.

Some still believe that Damien, Jason, and Jessie are guilty—that they used celebrity influence and media manipulation to escape justice. They see the Alford plea not as a compromise, but as a confession. They believe the right people were convicted in 1994, and releasing them was a betrayal of the three murdered children.

The case has torn families apart. Some relatives won’t speak to each other. Some have changed their minds multiple times over the years. Some have given up trying to find the truth and just want the whole nightmare to end.

John Mark Byers—Christopher’s stepfather—initially supported the guilty verdicts but later changed his mind and became an advocate for the West Memphis Three’s release. He now believes they’re innocent.

Thirty-two years later, there is still no consensus on who killed Stevie, Michael, and Christopher. And there may never be.

The Truth No One Can Find

Here’s what we know for certain: On May 5, 1993, three eight-year-old boys went into the woods to play and never came home. Their bodies were found the next day, beaten and bound. Three teenagers were arrested, tried, and convicted of their murders based largely on a questionable confession and circumstantial evidence. They spent eighteen years in prison. DNA testing excluded them from the crime scene evidence. They were released in 2011 under an Alford plea that allowed them to maintain their innocence while pleading guilty.

And thirty-two years later, no one has been definitively identified as the killer.

Here’s what we don’t know: Who actually murdered Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers. Whether Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley are innocent men who were wrongly convicted—or guilty men who manipulated the system and walked free. Whether Terry Hobbs was involved. Whether there was someone else entirely. Whether the truth will ever come out.

The West Memphis Three case isn’t a story with a neat ending. It’s a story about what happens when justice fails—or when we can’t agree on what justice even looks like.

It’s about three little boys who deserved better. Three teenagers who may or may not have killed them. A town that tore itself apart trying to find someone to blame. And a legal system that, in the end, offered freedom without exoneration—a compromise that satisfied no one and resolved nothing.

Damien Echols walks free today. But he’s still a convicted murderer. Jason Baldwin rebuilt his life. But the eighteen years he lost are gone forever. Jessie Misskelley went home to Arkansas. But the confession he gave—true or false—defined the rest of his life.

And somewhere—whether it’s behind bars, walking free under an Alford plea, living quietly in Arkansas, or buried in an unmarked grave—the person who killed Stevie, Michael, and Christopher has never been held fully accountable.

That’s the real injustice. Not just that three teenagers spent eighteen years in prison. But that three little boys never got the justice they deserved.

And maybe they never will.

Freedom without exoneration. Release without redemption.

Damien Echols walked out of that courtroom in 2011 a free man. But the state of Arkansas has never called him innocent.

And they never will.

When Fear Becomes Evidence

The West Memphis Three trials didn’t happen in a vacuum. They unfolded during the height of what historians now call the “Satanic Panic”—a moral hysteria that swept through America in the 1980s and 1990s.

It started with rumors. Whispers about secret cults performing rituals in basements. Stories of children being abused in daycare centers by devil-worshippers. Talk show hosts like Geraldo Rivera aired prime-time specials warning parents that Satanists were lurking in every community. Churches held seminars teaching people how to recognize “occult symbols”—pentagrams, inverted crosses, even heavy metal band logos.

By 1993, the panic had reached a fever pitch. Hundreds of innocent people across the country had been accused of participating in Satanic rituals. Dozens were convicted based on flimsy evidence and coerced testimony from children who later recanted. The San Antonio Four, the McMartin Preschool case, the Kern County cases—one by one, these convictions would eventually be overturned. But not before lives were destroyed.

West Memphis, Arkansas, was prime territory for this hysteria. Conservative, deeply religious, and fiercely protective of its children. When three eight-year-old boys turned up dead with injuries that police interpreted as “ritualistic,” the community didn’t just want answers. They wanted a monster.

And Damien Echols looked like one.

The prosecution’s case against him wasn’t built on forensic science. It was built on fear. Damien wore black clothes. He read books about Wicca. He listened to Metallica. In the eyes of West Memphis, that was enough.

At trial, prosecutors called witnesses who testified that Damien had told them he “drank blood” and “worshipped Satan”. They introduced his psychiatric records as evidence of a disturbed mind. They pointed to his poetry—dark, depressing verses about death and isolation—and suggested it was proof of murderous intent.

But they never explained how any of this connected to the actual crime.

There was no physical evidence linking Damien to Robin Hood Hills that night. No witnesses saw him there. No forensic proof placed him at the scene. The entire case rested on the assumption that someone who dressed like Damien and read the books he read must be capable of killing children in a Satanic ritual.

The jury believed it.

Years later, after DNA testing excluded all three defendants and the Satanic Panic subsided, legal scholars would look back at the West Memphis Three trials as a textbook example of wrongful conviction fueled by moral hysteria. But in March 1994, in a small Arkansas courtroom packed with grieving parents and terrified neighbors, fear was all the evidence the prosecution needed.

The Confession That Kept Falling Apart

Jessie Misskelley’s confession was the linchpin of the entire case. Without it, prosecutors had almost nothing. But the more closely anyone examined that confession, the more it crumbled.

Jessie was seventeen years old with an IQ between 67 and 75—borderline intellectually disabled. He functioned at the level of a child, according to his school records. On June 3, 1993, West Memphis police brought him in for questioning without a parent or attorney present.

The interrogation lasted twelve hours. For the first several hours, no tape recorder was running. What happened during that time remains disputed. Police claim they simply asked questions. Defense attorneys argue that Jessie was subjected to psychological coercion—promises of reward money, threats about what would happen if he didn’t cooperate, leading questions that fed him details about the crime.

Dr. Richard Ofshe, a social psychologist and expert on false confessions, later testified that Jessie’s interrogation bore all the hallmarks of coercion. Jessie had “low self-esteem” and was “mentally handicapped”—two factors that made him especially vulnerable to giving a false confession when subjected to “overly persuasive tactics”.

But Judge David Burnett refused to let Dr. Ofshe tell the jury that the confession was, in his expert opinion, coerced. “What the hell do we need a jury for?” Burnett asked during a closed hearing.

So the jury heard Jessie’s confession. And on the surface, it sounded damning.

But the details were all wrong.

Jessie said the murders happened in the morning. The medical examiner determined the boys died in the early morning hours—after midnight. Jessie said they tied the boys with rope. The victims were bound with their own shoelaces. Jessie said the boys were raped. There was no evidence of sexual assault.

Jessie said one boy was cut and mutilated in specific ways that didn’t match the autopsy findings. He described the location of injuries that weren’t there and missed injuries that were.

When police realized the confession didn’t match the crime scene, they brought Jessie back for more interrogations. Each time, they “corrected” his story—feeding him new details, adjusting the timeline, reshaping his account until it aligned better with what they knew.

By the time the taped confession was played in court, it had been rehearsed, edited, and refined through multiple sessions.

And even then, it still contained glaring inconsistencies.

Jessie recanted the confession as soon as he was released to his family. He told them police had threatened him and promised him reward money. He said he didn’t know anything about the murders—he’d just told them what they wanted to hear so they’d let him go.

But it was too late. The confession had already been used to arrest Damien and Jason. And even though Jessie refused to testify at their trial, even though his statement was barred from being introduced as evidence against them, the damage was done.

Everyone in West Memphis knew Jessie had confessed. Everyone knew he’d named Damien and Jason. And in a small town where news traveled fast, that knowledge poisoned the jury pool before the trial even began.

The Evidence That Was Never There

Police work in the West Memphis case was, by almost any standard, catastrophic.

Gary Gitchell, the lead detective, admitted under cross-examination that West Memphis police owned both video cameras and audio recorders—but hadn’t bothered to tape any of their interviews with Damien Echols. He couldn’t explain why.

Blood evidence collected from a Bojangles restaurant on the night of the murders—evidence that might have pointed to an alternative suspect—was lost. Gitchell testified that the samples were “as the term is, lost”. No one could explain how or when they disappeared.

The boys’ bicycles were found abandoned at the edge of Robin Hood Hills, but police never dusted them for fingerprints. If the killer had touched those bikes, his prints might have been there. No one bothered to check.

Fibers found on the victims’ bodies were tested, but the results were inconclusive. Police didn’t pursue further analysis.

A knife that John Mark Byers—Christopher Byers’s stepfather—had given to an HBO documentary crew was later turned over to police. The knife had human blood on it. Byers initially told authorities he had “no idea” how blood got on the knife, then later changed his story and claimed it came from a cut on his hand.

The knife was tested. The blood was indeed Byers’s. But prosecutors never investigated whether Byers might have been involved in the murders. They already had their suspects.

Another teenager, Christopher Morgan, had confessed to California police that he “might have blacked out” and killed the three boys in West Memphis. He later recanted. When defense attorneys tried to call Morgan to testify, his lawyer announced that Morgan would invoke his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

That’s exactly what the defense wanted—to create reasonable doubt by showing the jury that someone else had confessed to the crime. But prosecutors argued that allowing Morgan to take the Fifth would mislead the jury into thinking he was guilty when he was really just protecting himself from unrelated federal drug charges.

Judge Burnett agreed. He refused to let Morgan testify and warned everyone involved that anyone who mentioned his ruling to the press would be held in contempt.

The jury never heard about the alternative suspect who had confessed.

Legal scholars would later examine the West Memphis investigation and conclude that it represented “a threat to the integrity of the criminal justice system” due to prosecutorial misconduct and failure to disclose exculpatory evidence. A law review article published by the University of Arkansas at Little Rock stated bluntly: “The West Memphis Three case illustrates the threat to the integrity of the criminal justice system when police or prosecutors fail to comply with constitutional obligations designed to ensure fairness”.

But in 1994, none of that mattered. The prosecution had a confession—flawed as it was—and a narrative that resonated with a terrified community. They didn’t need forensic evidence.

They just needed a jury willing to believe that three strange teenagers were capable of unspeakable evil.

And they got one.

The Celebrities Who Wouldn’t Look Away

If not for HBO, the West Memphis Three might have died in prison.

In 1996, the documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills premiered on cable television. Filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky had spent months in Arkansas, filming the trials, interviewing the families, and documenting a case that raised more questions than answers.

The documentary didn’t take a firm stance on guilt or innocence. But it showed viewers something undeniable: three teenagers had been convicted of murder with no physical evidence, based largely on a confession from a boy with an IQ of 72 and a prosecution narrative rooted in Satanic Panic.

The film sparked outrage. Viewers flooded HBO with calls. Advocacy groups formed. And celebrities began to pay attention.

Johnny Depp was one of the first. He watched Paradise Lost and was horrified by what he believed was a grotesque miscarriage of justice. He began writing to Damien Echols on death row, sending him books, money, and encouragement. The two men formed an unlikely friendship—a Hollywood megastar and a condemned prisoner exchanging letters about literature, art, and the nature of injustice.

“Without Johnny Depp, I don’t know if I would have survived,” Damien said years later. “He gave me hope when I had none left”.

Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam, also took up the cause. He organized benefit concerts to raise money for legal appeals and spoke publicly about his belief that the West Memphis Three were innocent. Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks wore a t-shirt with Damien’s face on it during concerts, sparking controversy but also drawing attention to the case.

Henry Rollins, the punk rock icon, raised over $100,000 for new DNA testing. Metallica—the same band whose music had been used as “evidence” of Satanic influence at trial—allowed the filmmakers to use their songs in the Paradise Lost documentaries for free.

And then Peter Jackson got involved.

The Oscar-winning director of The Lord of the Rings trilogy had watched Paradise Lost and become convinced that Damien, Jason, and Jessie were innocent. In 2005, he and his wife Fran Walsh began funding a private investigation into the case. They hired forensic experts, paid for advanced DNA testing, and bankrolled legal appeals.

Jackson also commissioned a new documentary—West of Memphis, directed by Amy Berg and released in 2012. The film went deeper than Paradise Lost, uncovering evidence of police misconduct, prosecutorial overreach, and DNA results that pointed to an alternative suspect: Terry Hobbs.

“Without Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Johnny Depp, we would have been lost,” Damien said at a press conference in Toronto after his release. “We left Arkansas like refugees, just fleeing. They didn’t stop helping us once we were out of prison. Without them, we would have had absolutely nothing—no fresh clothes, no shelter, nothing”.

The celebrity support drew criticism from some quarters. Detractors argued that rich and famous people were using their influence to free guilty men—that the West Memphis Three had manipulated Hollywood into believing a false narrative of innocence.

But the celebrities didn’t just throw money at the problem. They used their platforms to force people to look at the evidence—or lack thereof. They asked uncomfortable questions: How could three teenagers be convicted of murder with no physical proof? Why was the confession of a mentally disabled boy taken as gospel when it contradicted the crime scene? Why hadn’t police investigated other suspects?

The movement they sparked didn’t just free the West Memphis Three. It changed the way America thinks about wrongful convictions, false confessions, and the danger of moral panic in the courtroom.

The Plea That Broke Jason Baldwin’s Heart

When the Alford plea was offered in August 2011, two of the three men accepted it immediately.

Damien Echols was on death row, facing execution. For him, the choice was simple: plead guilty and walk free, or reject the deal and risk being strapped to a gurney.

Jessie Misskelley had spent eighteen years grappling with the confession that had destroyed three lives—including his own. The Alford plea offered a way out, a chance to start over.

But Jason Baldwin refused.

He’d been sixteen years old when he was sentenced to life without parole. He’d spent eighteen years insisting he was innocent—writing letters, filing appeals, waiting for the system to admit it had made a mistake. And now, after all that time, after all that fight, the state of Arkansas was offering him freedom—but only if he admitted guilt.

Even under the Alford structure, which allowed him to maintain his innocence while pleading guilty, it felt like a betrayal. It felt like giving up.

“I don’t think I could live with myself if I took this deal,” Jason told his attorneys.

But Damien was still on death row.

If Jason rejected the plea, the case would go back to trial. It could take years. And during those years, Damien would remain on death row, waiting for an execution date that could come at any time.

Jason couldn’t live with that either.

So on August 19, 2011, he stood before Judge David Laser and entered an Alford plea to three counts of first-degree murder. His voice shook when he spoke. Tears streamed down his face.

He walked out of the courthouse a free man. But he would never call it victory.

“This was not justice,” he told reporters outside. “This was a compromise. I didn’t kill anybody, and the state of Arkansas knows it. But they’d rather let guilty men walk free than admit they made a mistake”.

Life on the Outside

Damien Echols walked out of prison on August 19, 2011, at thirty-seven years old. He’d spent eighteen years on death row—half his life. The world he stepped into was unrecognizable.

In 1993, there were no smartphones. No social media. No streaming services. The internet existed, but barely. By 2011, the entire culture had shifted. Damien didn’t know how to use an iPhone. He’d never seen a Marvel movie. He’d never heard of Facebook.

“It was like being dropped onto an alien planet,” he said in interviews.

He and his wife Lorri fled Arkansas immediately. “We left like refugees,” Damien said. They moved to New York, where Peter Jackson and Johnny Depp had arranged housing and financial support.

In 2012, Damien published his memoir, Life After Death. The book became a bestseller, praised for its raw honesty and literary quality. Johnny Depp wrote the foreword, comparing Damien’s prose to Dostoyevsky. The cover was designed in the style of Shepard Fairey’s iconic “Hope” poster—a visual echo of the movement that had helped free him.

Damien became an artist, a writer, a public speaker. He practiced ceremonial magic—spelled “magick” in the tradition of Aleister Crowley. He talked openly about the trauma of incarceration, the psychological toll of solitary confinement, the surreal experience of being simultaneously celebrated as a symbol of injustice and condemned as a convicted murderer.

Because that’s what he still was. Under the terms of the Alford plea, Damien’s criminal record listed him as guilty of three counts of first-degree murder. He couldn’t vote. He couldn’t own a gun. Every background check, every job application, every piece of government paperwork marked him as a killer.

And he could never sue the state of Arkansas for wrongful imprisonment. That was part of the deal. In exchange for freedom, he had to forfeit his right to seek compensation for the eighteen years they took from him.

Legal experts estimate that if Damien had been fully exonerated, he would have been entitled to approximately $18 million in damages.

Instead, he got nothing.

Jason Baldwin stayed out of the spotlight. He moved quietly, trying to rebuild a life that had been stolen when he was sixteen. He’d lost his late teens, his entire twenties, his early thirties. Those years were gone. He couldn’t get them back.

Jessie Misskelley returned to Arkansas and enrolled in community college to study auto mechanics. He got engaged to his high school girlfriend. He tried to live a normal life—as normal as possible for someone who spent half his life in prison for murders he may or may not have had anything to do with.

None of them talk much about the case anymore. They’ve moved on as best they can. But the shadow of West Memphis follows them everywhere.

The Hunt for New Answers

In August 2025, something remarkable happened.

After years of legal battles, Judge Tonya Alexander granted permission for advanced DNA testing on evidence from the West Memphis crime scene—evidence that had long been thought destroyed or lost.

The testing will use cutting-edge genetic genealogy techniques—the same methods that identified the Golden State Killer and dozens of other cold case suspects. If any foreign DNA exists on the ligatures that bound the three boys, scientists believe they can now extract it and build a genetic profile.

That profile could finally answer the question that has haunted this case for thirty-two years: Who killed Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers?

If the DNA points to Damien, Jason, or Jessie, it would validate the original convictions—suggesting that the Alford plea was, in fact, an admission of guilt.

If the DNA excludes them entirely, it could lead to full exoneration—wiping their records clean and potentially opening the door for wrongful imprisonment lawsuits.

And if the DNA matches Terry Hobbs—or someone else entirely—it could finally bring charges in a case that has remained unsolved despite three convictions.

But there’s a catch.

Much of the evidence is missing. In 2024, when Damien’s legal team requested access to the evidence for testing, they discovered that boxes of materials had vanished. Items that should have been preserved under Arkansas law were gone—destroyed, lost, or never properly cataloged in the first place.

“We are deeply concerned about the sequence of events,” Damien’s attorney Patrick Benca said. “Was the evidence lost after we requested advanced DNA testing? What evidence is left? Where does that evidence reside now?”

No one from the West Memphis Police Department has answered those questions.

The testing on the remaining evidence is ongoing. Results are expected sometime in 2026.

Until then, the truth remains elusive.

The Question With No Answer

Thirty-two years have passed since three eight-year-old boys rode their bikes into Robin Hood Hills and never came home.

Thirty-two years since their bodies were pulled from a drainage ditch, bound and beaten.

Thirty-two years since West Memphis police arrested three teenagers based on a coerced confession and a community’s fear of Satanic cults.

And after all this time, after all the trials and appeals and documentaries and DNA tests, one question still has no definitive answer: Who killed Stevie Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers?

Was it Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley—three teenagers who spent eighteen years in prison, took an Alford plea, and walked free with criminal records that still mark them as murderers?

Was it Terry Hobbs, whose DNA was found at the crime scene and whose behavior after the murders raised questions that were never fully investigated?

Was it someone else entirely—a transient, a serial killer, a suspect who slipped away while police focused all their attention on three strange kids who didn’t fit in?

We may never know.

What we do know is this: Three little boys are dead. Three men spent eighteen years in prison. And the American justice system, faced with overwhelming evidence that it had made a catastrophic mistake, chose not to admit error.

Instead, it offered a compromise.

Freedom without exoneration. Release without redemption. A legal maneuver that allowed everyone to save face while resolving nothing.

The families of the victims remain divided. Some believe justice was served in 1994. Others believe the real killer is still out there.

The West Memphis Three walk free. But they will never be called innocent.

And somewhere—whether behind bars, walking the streets, or buried in an unmarked grave—the person who killed Stevie, Michael, and Christopher has never been held fully accountable.

That’s the legacy of the West Memphis Three case. Not justice. Not truth. Just an uneasy compromise that satisfied no one and answered nothing.

Damien Echols is free. But the state of Arkansas has never said he’s innocent.

And they never will.